Editor’s note: This was the third-place submission, out of nineteen, to Fordham’s 2019 Wonkathon, in which we asked participants to answer the question: “What’s the best way to help students who are several grade levels behind?”

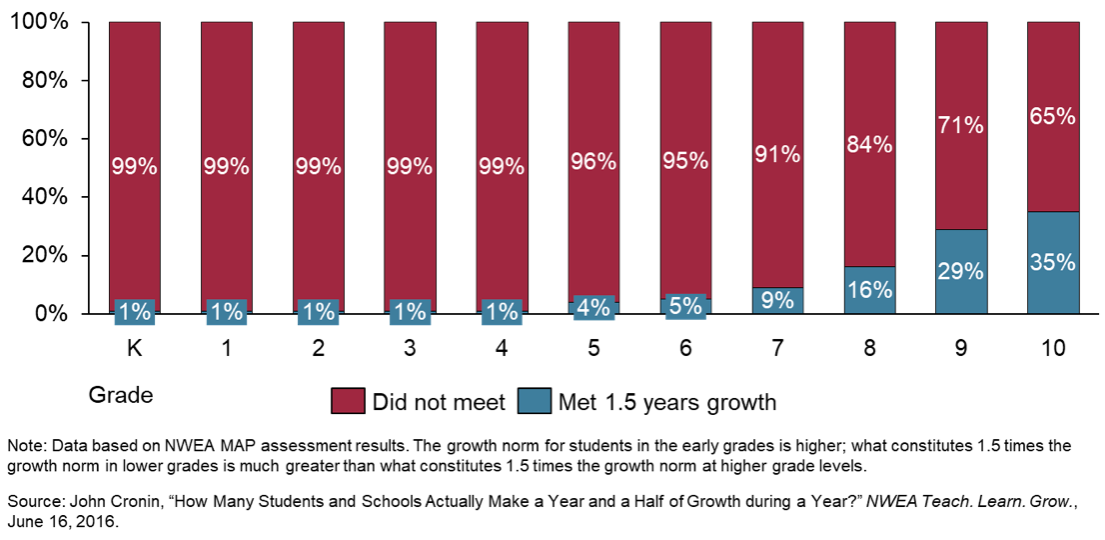

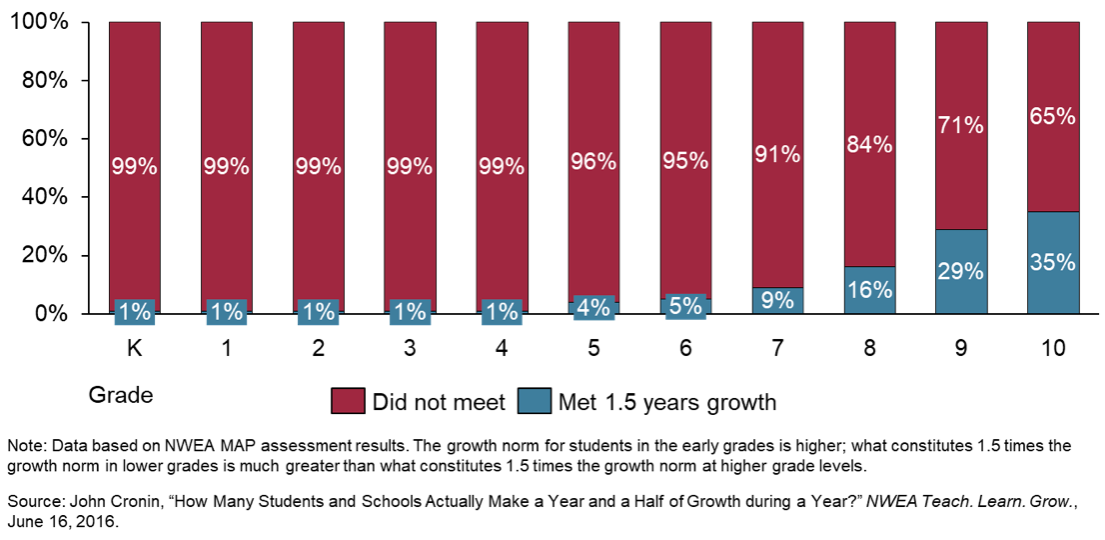

Despite enormous effort across the education sector over many years, persistent and pervasive gaps in educational access, engagement, and achievement exist for students across the country. To this day, the majority of black, Latinx, Native American, and low-income students do not receive the education they need to meet grade-level standards and be ready for college or career. Students who fall below grade level rarely catch up, even when schools make concerted efforts to accelerate growth. As the figure below demonstrates, only a tiny minority of elementary and middle schools successfully support low-performing students to achieve gap-closing levels of growth.

Figure 1. Proportion of schools with low-performing students averaging 1.5 years of growth in mathematics

In response, two seemingly competing schools of thought have emerged among education policy leaders and the creators and consumers of instructional materials and curricula—one focused on attaining grade level proficiency for all, and the other focused on individualized student growth.

The proficiency-focused group identifies the problem in the fact that when students enter the classroom performing below grade level, they are too rarely given opportunities to learn grade level content. These students are disproportionately low-income students of color. Proposed solutions from this camp: grade-level materials and rigorous, grade-level aligned expectations, to allow students to rise to expectations and truly catch up. Those in this camp are likely to advocate for curricula aligned with rigorous grade-level standards, or accountability measures focused on communicating high expectations, as well as increased support and direction for teachers on instructional techniques that can bring students to grade level and beyond.

The growth-focused school of thought sees teachers struggling to effectively support students with a broad range of abilities as the problem, which results in students progressively disengaging from work that seems too difficult. They want to enable teachers to understand and address students’ individual needs and to engage students with instructional materials that challenge them from where they are now. They often use technology to help make the process of personalization attainable. And they favor growth-focused policy incentives and school/classroom models that break the mold of grade-level groupings.

To the wonk-o-sphere, this might seem like an intractable clash, especially when it comes to effectively supporting students who enter the classroom far below grade level. But leaders in the field must stop perpetuating the myth of a divide. Our recent research showed us schools and classrooms across the country where educators and students disprove this binary thinking on a daily basis. They know that closing learning gaps requires students to be motivated and engaged to grapple with challenging, grade-level skills and knowledge—while also having their individual learning needs met.

Through our research, we found that three key things are true of schools that succeed at accelerating growth among students who start off below grade level:

- Students have access to meaningful learning experiences that actively engage and challenge them, and respond to their individual needs, interests, and contexts. This kind of learning experience requires educators to have deep personal knowledge of their students. Knowing a student deeply is not superfluous—it is a foundation on which to build relationships and can be a powerful lever for engagement.

- Educators and school leaders have supports and professional learning opportunities that are individualized to each teacher, collaborative across grade levels, grounded in student data, and embedded in strong school systems and culture. In successful schools, teachers are prepared to lead dynamic classrooms where students are constantly engaged in rigorous work. Teachers constantly assess and act on students’ strengths, needs, and gaps, leveraging variety of materials and tools to do so. Leaders and administrators in these schools share and communicate clear expectations about how to use and adapt instructional materials in support of students’ goals.

- Instructional materials are robust, coherent, and actually usable. High-quality core instructional materials and supplemental aligned supports and tools for intervention, often leveraging technology and data, are critical to classroom practice. These materials form the backbone of rigor and personalization across every classroom. The most successful schools spend significant time and effort putting these pieces together and adapting them to meet student and teacher needs.

Sadly, schools where all three realities exist are still a rarity. But by following the lead of these educators, leaders and policymakers can ensure more students achieve their college and career goals.

What needs to change in our policies and systems to bring about these conditions in more schools? The short answer is: a lot. There is no one solution to meet the needs of students far below grade level, or one clear policy barrier standing in the way of progress. For example, the vast majority of states’ accountability systems value both proficiency and growth, which was not the case just a few years ago. The long-term answer must include a peace agreement between the growth and proficiency camps, and moving forward, a shared commitment to improvements in instructional materials and educator development.

The definition of quality in instructional materials and educator development should center on what we know from learning science, educational research, and schools doing this work every day: Facilitating growth and aiming for excellence are entirely compatible goals, and each can reinforce the other.

Right now, teachers are the ones left to navigate the complexity. Teachers are currently on the receiving end of too many mixed messages in preparation programs and professional development about what it means to achieve grade-level rigor and “stick to the standards” while also cultivating deep relationships and personalized learning opportunities for individual students. Within schools, better educator development means creating space for collaboration, building shared understanding of student data, and emphasizing both rigor and personalization. It may be that achieving this kind of learning environment will require new kinds of school and classroom organizational structures.

There is currently a significant amount of work happening in the field to bring high-quality instructional materials into classrooms, but little reason for vendors and content providers to collaborate and make their systems work better together for end users. If we want more schools to adopt the highest-quality instructional materials, those materials ought to be flexible enough to attend to the needs and interests of a diverse group of learners, and should also play nicely with all the other functional components of a classroom and school, from attendance to assessment.

Teachers should be meeting students where they are academically, and supporting students to reach rigorous, grade-level expectations. In order to help them to do this, policymakers at the district, state, and federal level, as well as private funders, can step in to exert pressure via procurement policies, accountability structures, curriculum adoption measures, and other incentives. At the same time, innovation, quality, and impact evaluation all take time, and expecting results in three-year funding cycles can stifle innovation.

Our research efforts lead us to the conclusion that achieving dramatic outcomes for students (especially those who need it most) will require a system-wide and holistic approach. This might not be the simple policy-change answer some wonks hope for, but it is the kind of change students and schools actually need.