As I write this, representative samples of fourth and eighth graders are taking National Assessment of Educational Progress tests in math and English. These exams must be held every two years in accordance with federal law to determine how well ongoing education reforms are working, whether achievement gaps between key demographic groups are growing or shrinking, and to what extent the nation is still “at risk” due to weakness in its K–12 system. Best known as “The Nation’s Report Card,” the NAEP results have long displayed student achievement in two ways: as points on a stable vertical scale that typically runs from 0 to 300 or 500 and as the percentages of test takers whose scores reach or surpass a trio of “achievement levels.” These achievement levels—dubbed “basic,” “proficient,” and “advanced”—were established by the National Assessment Governing Board, an almost-independent twenty-six-member body, and have resulted in the closest thing America has ever had to nationwide academic standards.

Though the NAEP achievement levels have gained wide acceptance amongst the public and in the media, they are not without their detractors. At the outset, the idea that NAEP would set any sort of achievement standards was controversial; what business had the federal government in getting involved with the responsibilities of states and localities? Since then, critics have complained that the achievement levels are too rigorous and are used to create a false sense of crisis. Now, even after three decades, the National Center for Education Statistics continues to insist that the achievement levels should be used on a “trial basis.”

How and why all this came about is quite a saga, as is the blizzard of controversy and pushback that has befallen the standards since day one.

Recognizing the need for performance comparisons

In NAEP’s early days, results were reported according to how test takers fared on individual items. It was done this way both because NAEP’s original architects were education researchers and because the public-school establishment demanded that this new government testing scheme not lead to comparisons between districts, states, or other identifiable units of the K–12 system. Indeed, for more than two decades after the exams’ inception in 1969, aggregate NAEP data were generated only for the nation as a whole and four large geographic quadrants. In short, by striving to avoid political landmines while pleasing the research community, NAEP’s designers had produced a new assessment system that didn’t provide much of value to policymakers, education leaders, journalists, or the wider public.

Early critical appraisals pointed this out and suggested a different approach. A biting 1976 evaluation by the General Accounting Office said that “unless meaningful performance comparisons can be made, states, localities, and other data users are not as likely to find the National Assessment data useful.” Yet nothing changed until 1983, when two events heralded major shifts in NAEP.

The first stemmed from a funding competition held by the National Institute of Education. That led to moving the main contract to conduct NAEP to the Princeton-based Educational Testing Service from the Denver-based Education Commission of the States. ETS’s successful proposal described plans to overhaul many elements of the assessment, including how test results would be scored, analyzed, and reported.

The noisier event that year, of course, was the declaration by the National Commission on Excellence in Education that the nation was “at risk” because its schools weren’t producing adequately educated graduates. Echoed and amplified by education secretaries Terrel Bell and Bill Bennett, as well as President Reagan himself, A Nation at Risk led more state leaders to examine their K–12 systems and find them wanting. But they lacked clear, comparative data by which to gauge their shortcomings and monitor progress in reforming them. The U.S. Department of Education had nothing to offer except a chart based on SAT and ACT scores, which dealt only with a subset of students near the end of high school. NAEP was no help whatsoever. The governors wanted more.

Some of this they undertook on their own. In mid-decade, the National Governors Association, catalyzed by Tennessee governor Lamar Alexander, launched a multi-year education study-and-renewal effort called “Time for Results” that highlighted the need for better achievement data. And the Southern Regional Education Board (also prompted by Alexander) persuaded a few member states to experiment with the use of NAEP tests to compare themselves.

At about the same time, Secretary Bennett named a blue-ribbon “study group” to recommend possible revisions to NAEP. Ultimately, that group urged major changes, almost all of which were then endorsed by the National Academy of Education. This led the Reagan administration to negotiate with Senator Ted Kennedy a full-fledged overhaul that Congress passed in 1988, months before the election of George H.W. Bush, whose campaign for the Oval Office included a pledge to serve as an “education president.”

The NAEP overhaul was multi-faceted and comprehensive, but, in hindsight, three provisions proved most consequential. First, the assessment would have an independent governing board charged with setting its policies and determining its content. Second, in response to the governors’ request for better data, NAEP was given authority to generate state-level achievement data on a “trial” basis. Third, its newly created governing board was given leeway to “identify” what the statute called “appropriate achievement goals for each age and grade in each subject to be tested.” (A Kennedy staffer later explained that this wording was “deliberately ambiguous” because nobody on Capitol Hill was sure how best to express this novel, inchoate, and potentially contentious assignment.)

In September 1988, as Reagan’s second term neared an end and Secretary Bennett and his team started packing up, Bennett named the first twenty-three members to the new National Assessment Governing Board. He also asked me to serve as its first chair.

The lead up to achievement levels

The need for NAEP achievement standards had been underscored by the National Academy of Education: “NAEP should articulate clear descriptions of performance levels, descriptions that might be analogous to such craft rankings as novice, journeyman, highly competent, and expert… Much more important than scale scores is the reporting of the proportions of individuals in various categories of mastery at specific ages.”

Nothing like that had been done before, though ETS analysts had laid essential groundwork with their creation of stable vertical scales for gauging NAEP results. They even placed markers at fifty-point intervals on those scales and used those as “anchors” for what they termed “levels of proficiency,” with names like “rudimentary,” “intermediate,” and “advanced.” Yet there was nothing prescriptive about the ETS approach. It did not say how many test takers should be scoring at those levels.

Within months of taking office, George H.W. Bush invited all the governors to join him—forty-nine turned up—at an “education summit” in Charlottesville, Virginia. Their chief product was a set of wildly ambitious “national education goals” that Bush and the governors declared the country should reach by century’s end. The third of those goals stated that “By the year 2000, American students will leave grades four, eight, and twelve having demonstrated competency in challenging subject matter including English, mathematics, science, history, and geography.”

It was a grand aspiration, never mind the unlikelihood that it could be achieved in a decade and the fact that there was no way to tell if progress were being made. At the summit’s conclusion, the United States had no mechanism by which to monitor progress toward that optimistic target, no agreed-upon way of specifying it, nor yet any reliable gauge for reporting achievement by state (although the new NAEP law allowed for this). But such tools were obviously necessary for tracking the fate of education goals established by the governors and president.

They wanted benchmarks, too, and wanted them attached to NAEP. In March 1990, just six months after the summit, the National Governors Association encouraged NAGB to develop “performance standards,” explaining that the “National Education Goals will be meaningless unless progress toward meeting them is measured accurately and adequately, and reported to the American people.”

Conveniently, if not entirely coincidentally, NAGB had already started moving in this direction at its second meeting in January 1989. As chair, I said that “we have a statutory responsibility that is the biggest thing ahead of us to—it says here: ‘identify appropriate achievement goals for each age and grade in each subject area to be tested.’ …It is in our assignment.”

I confess to pushing. I even exaggerated our mandate a bit, for what Congress had given the board was not so much assignment as permission. But I felt the board had to try to do this. And, as education historian Maris Vinovskis recorded, “members responded positively” and “NAGB moved quickly to create appropriate standards for the forthcoming 1990 NAEP mathematics assessment.”

In contrast to ETS’s useful but after-the-fact and arbitrary “proficiency levels,” the board’s staff recommended three achievement levels. In May 1990, NAGB voted to proceed—and to begin reporting the proportion of students at each level. Built into our definition of the middle level, dubbed “proficient,” was the actual language of the third goal set in Charlottesville: “This central level represents solid academic performance for each grade tested—four, eight, and twelve. It will reflect a consensus that students reaching this level have demonstrated competency over challenging subject matter.”

Thus, just months after the summit, a standard-setting and performance-monitoring process was in the works. I accept responsibility for nudging my NAGB colleagues to take an early lead on this, but they needed minimal encouragement.

Early attempts and controversies

In practice, however, this proved to be a heavy lift for a new board and staff, as well as a source of great contention. Staff testing specialist Mary Lyn Bourque later wrote that “developing student performance standards” was “undoubtedly the board’s most controversial responsibility.”

The first challenge was determining how to set these levels, and who would do it. As Bourque recounted, we opted to use “a modified Angoff method” with “a panel of judges who would develop descriptions of the levels and the cut scores on the NAEP score scale.” The term “modified Angoff method” has reverberated for three decades now in connection with those achievement levels. Named for ETS psychologist William Angoff, this procedure is widely used to set standards on various tests. At its heart is a panel of subject-matter experts who examine every question and estimate how many test takers might answer it correctly. The Angoff score is commonly defined as the lowest cutoff score that a “minimally qualified candidate” is likely to achieve on a test. The modified Angoff method uses the actual test performance of a valid student sample to adjust those predicted cutoffs in case reality doesn’t accord with expert judgments.

As the NAEP level-setting process got underway, there were stumbles, missteps, and miscalculations. Bourque politely wrote that the first round of standard-setting was a “learning experience for both the board and the consultants it engaged.” It consumed just three days, which proved insufficient, leading to follow-up meetings and a dry run in four states. It was still shaky, however, leading the board to dub the 1990 cycle a trial and to start afresh for 1992. The board also engaged an outside team to evaluate its handiwork.

Those reviewers didn’t think much of it, reaching some conclusions that in hindsight had merit but also many that did not. But the consultants destroyed their relationship with NAGB by distributing their draft critique without the board’s assent to almost 40 others, “many of whom,” wrote Bourque, “were well connected with congressional leaders, their staffs, and other influential policy leaders in Washington, D.C.” This episode led board members to conclude that their consultants were keener to kill off the infant level-setting effort than to perfect its methodology. That contract was soon canceled, but this episode qualified as the first big public dust-up over the creation and application of achievement levels.

NCLB raises the stakes

Working out how best to do those things took time, because the methods NAGB used, though widespread today, were all but unprecedented at the time. In Bourque’s words, looking back from 2007, using achievement-level descriptions “in standard setting has become de rigueur for most agencies today; it was almost unheard of before the National Assessment.”

Meanwhile, criticism of the achievement-level venture poured in from many directions, including such eminent bodies as the National Academy of Education, National Academy of Sciences, and General Accounting Office. Phrases like “fundamentally flawed” were hurled at NAGB’s handiwork.

The achievement levels’ visibility and combustibility soared in the aftermath of No Child Left Behind, enacted in early 2002, for that law’s central compromise left states in charge of setting their own standards while turning NAEP into auditor and watchdog over those standards and the veracity of state reports on pupil achievement. Each state would report how many of its students were “proficient” in reading and math according to its own norms as measured on its own tests. Then, every two years, NAEP would report how many of the same states’ students at the same grade levels were proficient in reading and math according to NAGB’s achievement levels. When, as often happened, there was a wide gap—nearly always in the direction of states presenting a far rosier picture of pupil attainment than did NAEP—it called into question the rigor of a state’s standards and exam scoring. On occasion, it was even said that such-and-such a state was lying to its citizens about its pupils’ reading and math prowess.

In response, of course, it was alleged that NAEP’s levels were set too high, to which the board’s response was that its “proficient” level was intentionally aspirational, much like the lofty goals framed back in Charlottesville. It wasn’t meant to shed a favorable light on the status quo; it was all about what kids ought to be learning, coupled with a comparison of present performance to that aspiration.

Some criticism was constructive, however, and the board and its staff and contractors—principally the American College Testing organization—took it seriously and adjusted the process, including a significant overhaul in 2005.

Tensions with the National Center for Education Statistics

Statisticians and social scientists want to work with data, not hopes or assertions, with what is, not what should be. They want their analyses and comparisons to be driven by scientific norms such as validity, reliability, and statistical significance, not by judgments and aspirations. Hence the National Center for Education Statistics’ own statisticians resisted the board’s standard-setting initiative for years. At times, it felt like guerrilla warfare as each side enlisted external experts and allies to support its position and find fault with the other.

As longtime NCES commissioner Emerson Elliott reminisces on those tussles, he explains that his colleagues’ focus was “reporting what students know and can do.” Sober-sided statisticians don’t get involved with “defining what students should do,” as that “requires setting values that are not within their purview. NCES folks were not just uncomfortable with the idea of setting achievement levels, they believed them totally inappropriate for a statistical agency.” He recalled that one of his senior colleagues at NCES was “appalled” when he learned what NAGB had in mind. At the same time, with the benefit of hindsight, Elliott acknowledges that he and his colleagues knew that something more than plain data was needed.

By 2009, after NAEP’s achievement levels had come into widespread use and a version of them had been incorporated into Congress’s own accountability requirements for states receiving Title I funding, the methodological furor was largely over. A congressionally mandated evaluation of NAEP that year by the Universities of Nebraska and Massachusetts finally recognized the “inherently judgmental” nature of such standards, noting the “residual tension between NAGB and NCES concerning their establishment,” then went on to acknowledge that “many of the procedures for setting achievement levels for NAEP are consistent with professional testing standards.”

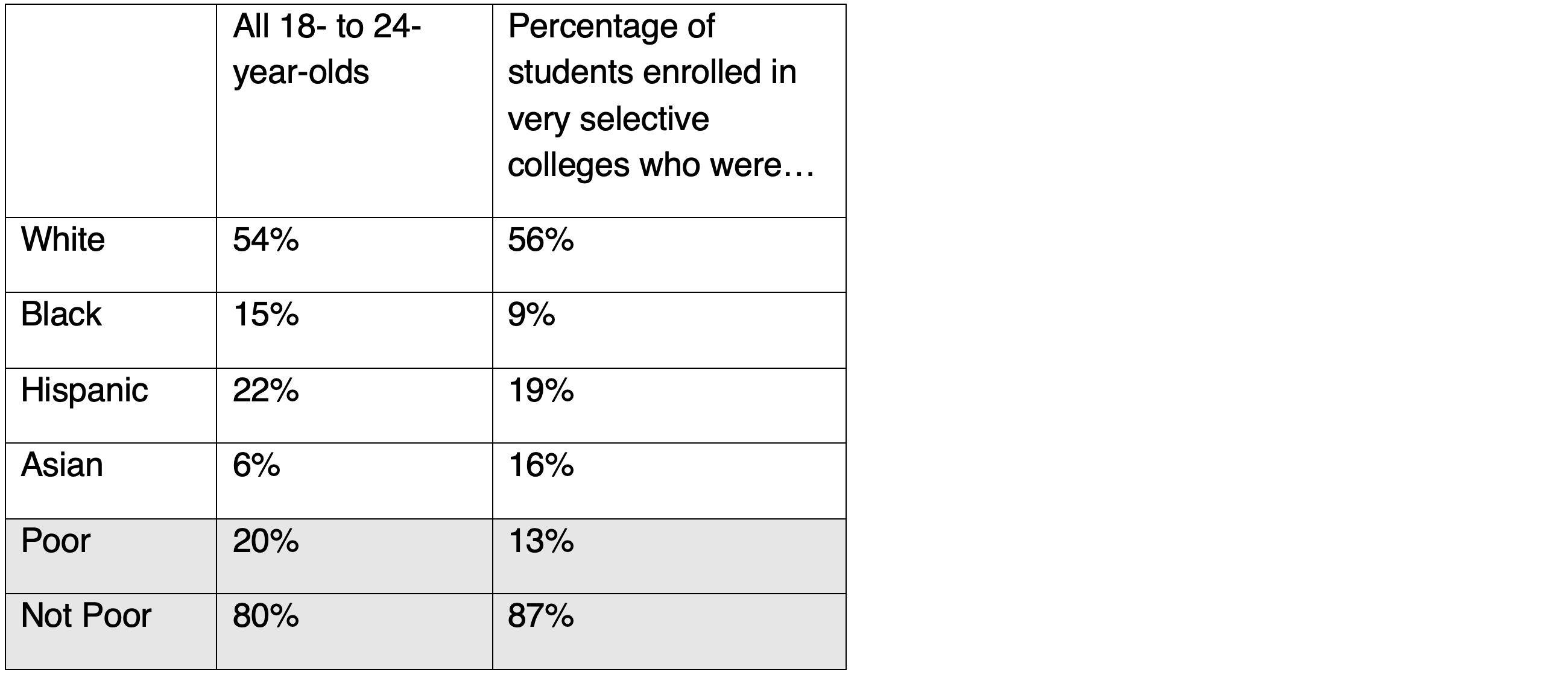

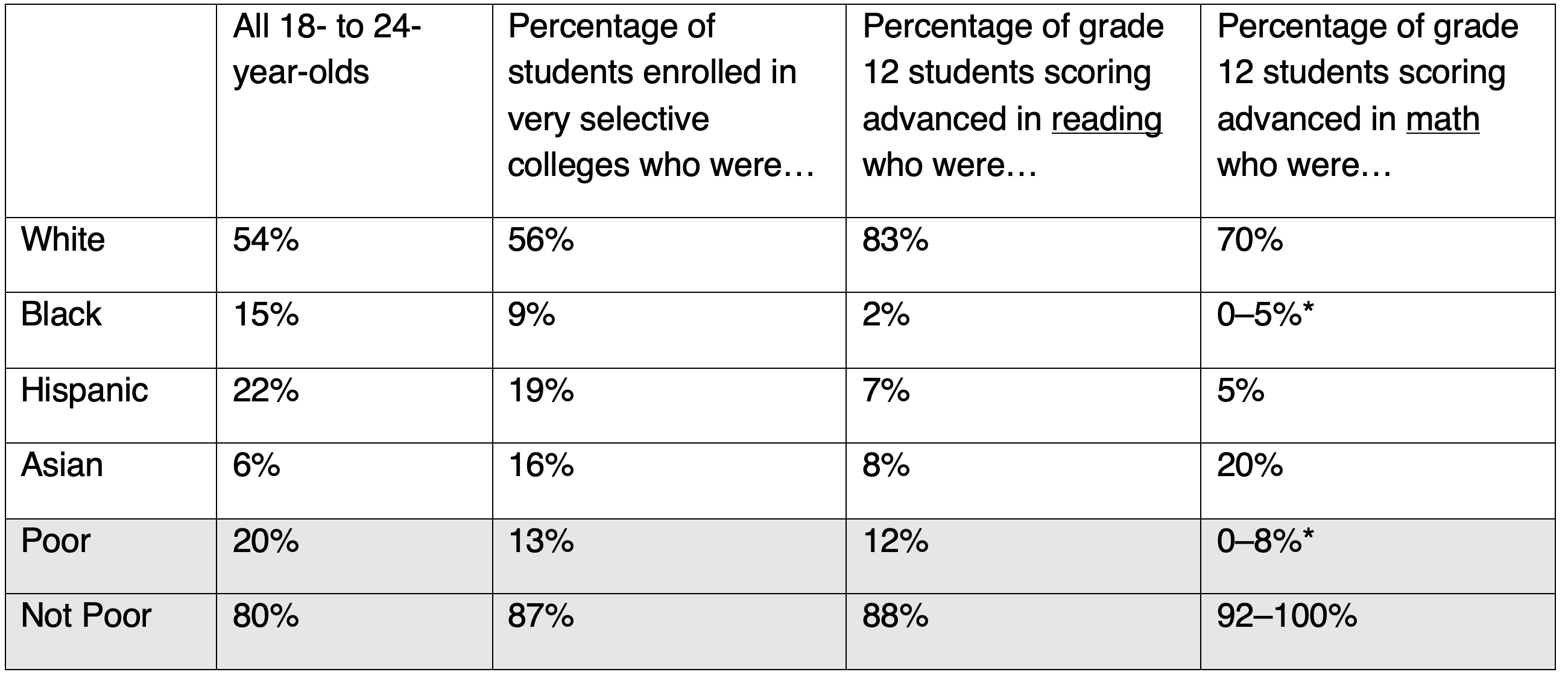

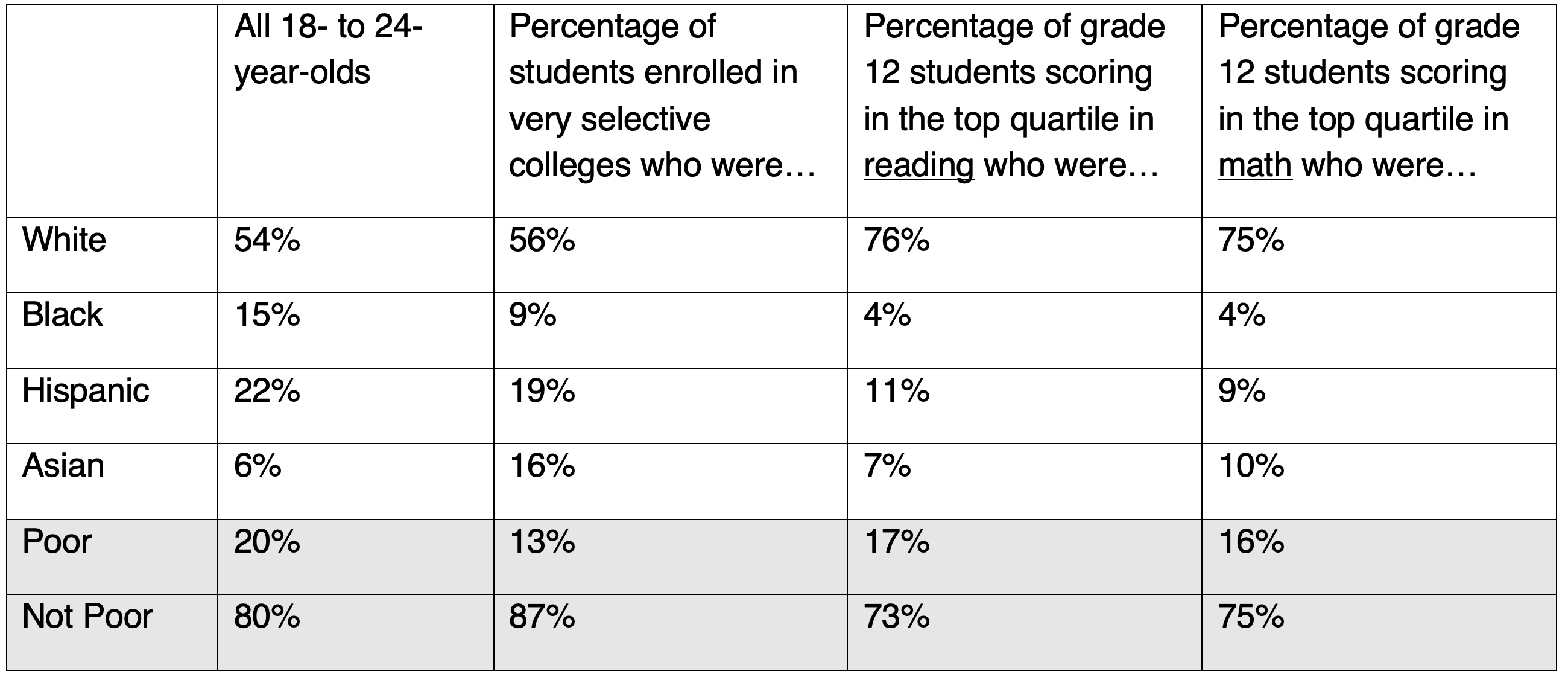

That positive review’s one big caveat faulted NAGB’s process for not using enough “external evidence” to calibrate the validity of its standards. Prodded by such concerns, as well as complaints that “proficient” was set at too high a level, the board commissioned additional research that eventually bore fruit. The achievement levels turn out to be more solidly anchored to reality, at least for college-bound students, than most of their critics have supposed. “NAEP-proficient” at the twelfth-grade level turns out to mean “college ready” in reading. College readiness in math is a little below the board’s proficient level.

As the years passed, NAGB and NCES also reached a modus vivendi for presenting NAEP results. Simply stated, NCES “owns” the vertical scales and is responsible for ensuring that the data are accurate, while NAGB “owns” the achievement levels and the interpretation of results in relation to those levels. The former may be said to depict “what is,” while the latter is based on judgments as to how students are faring in relation to the question “how good is good enough?” Today’s NAEP report cards incorporate both components, and the reader sees them as a seamless sequence.

Yet the tension has not entirely vanished. The sections of those reports that are based on achievement levels continue to carry this note: “NAEP achievement levels are to be used on a trial basis and should be interpreted and used with caution.” The statute still says, as it has for years, that the NCES commissioner gets to determine when “the achievement levels are reasonable, valid, and informative to the public,” based on a formal evaluation of them. To date, despite the widespread acceptance and use of those levels, that has not happened. In my view, it’s long overdue.

Looking ahead

Accusations continue to be hurled that the achievement levels are set far too high. Why isn’t “basic” good enough? And—a concern to be taken seriously—what about all those kids, especially the very large numbers of poor and minority pupils, whose scores fall “below basic?” Shouldn’t NAEP provide much more information about what they can and cannot do? After all, the “below basic” category ranges from completely illiterate to the cusp of essential reading skills.

The achievement-level refresh that’s now underway is partly a response to a 2017 recommendation from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that urged an evaluation of the “alignment among the frameworks, the item pools, the achievement-level descriptors, and the cut scores,” declaring such alignment “fundamental to the validity of inferences about student achievement.” The board engaged the Pearson testing firm to conduct a sizable project of this sort. It’s worth underscoring, however, that this is meant to update and improve the achievement levels, their descriptors, and how the actual assessments align with them, not to replace them with something different.

I confess to believing that NAEP’s now-familiar trinity of achievement levels has added considerable value to American education and its reform over the past several decades. Despite all the contention that they’ve prompted over the years, I wouldn’t want to see them replaced. But to continue measuring and reporting student performance with integrity, they do require regular maintenance.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published by Education Next.