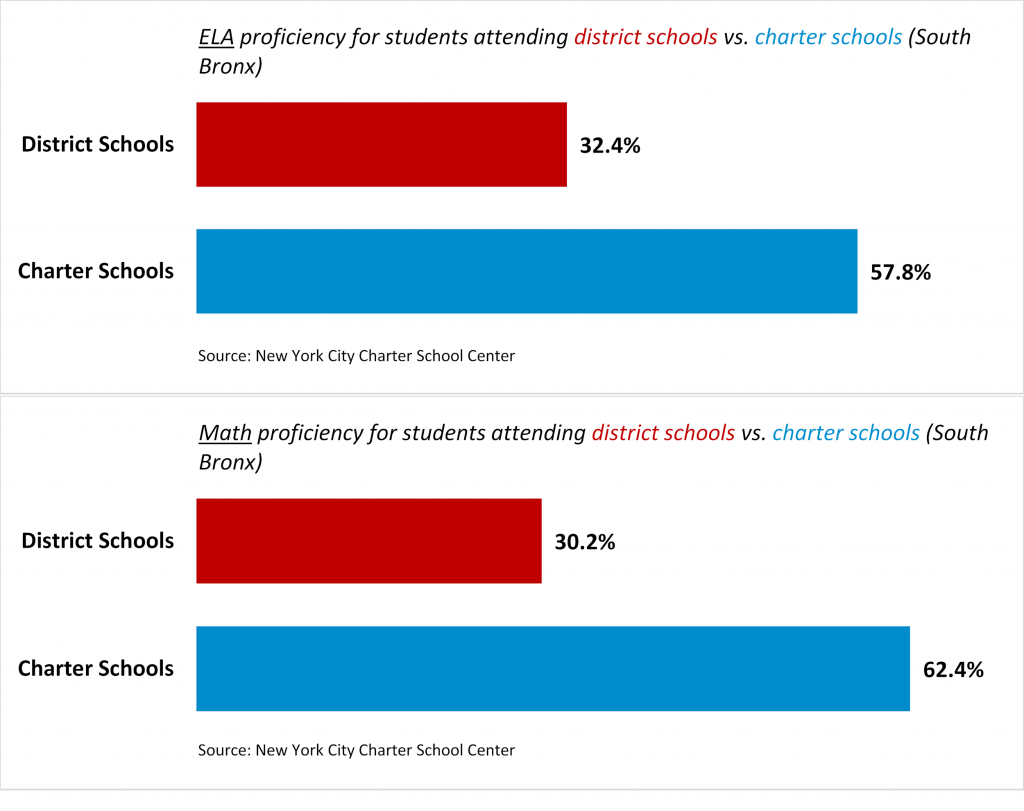

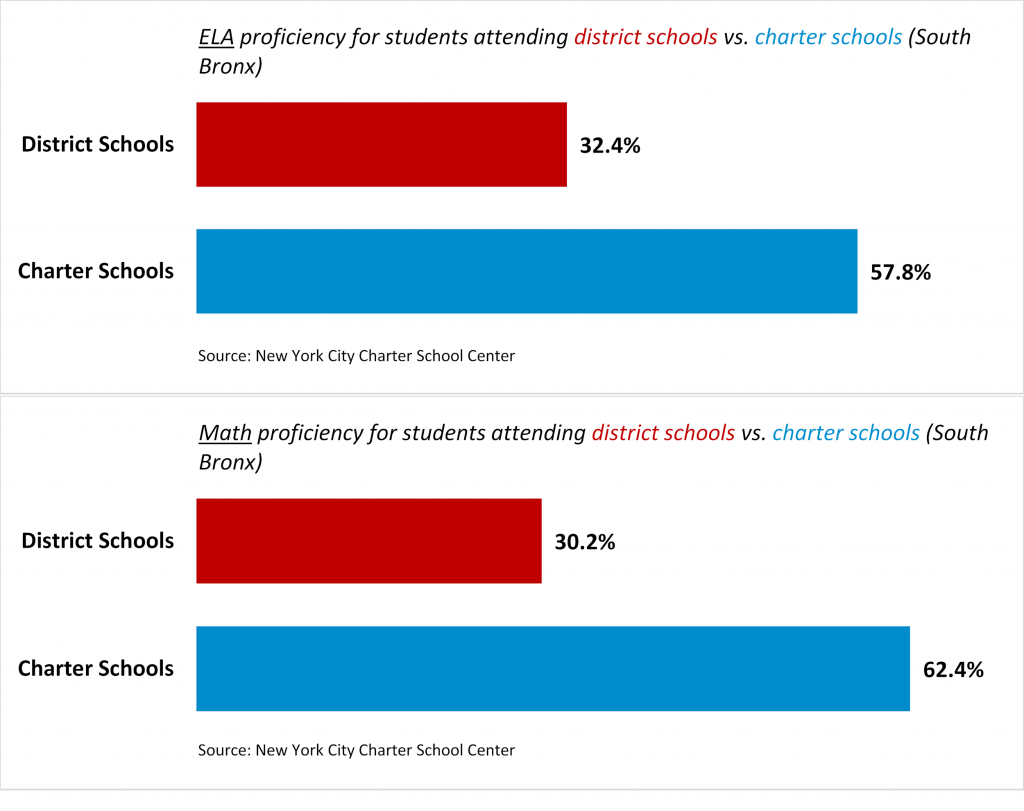

Of the nearly 2,000 public school students beginning high school in the South Bronx (District 8 of NYC public schools) in 2015, only 2 percent graduated ready for college four years later. A shocking 98 percent of students either dropped out of high school before completing their senior year—or they did manage to graduate, but would still be required to take remedial classes in community college due to low math and reading scores on state exams. By contrast, charter public schools in the South Bronx continued to outperform their district peers in both math and reading for third through eighth graders by a substantial margin in 2019, as shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: District versus charter school proficiency in English language arts and math, 2019

Source: New York City Charter School Center

It comes as no surprise that parents in this predominantly Black and Hispanic community, encompassing two of the poorest Congressional districts in the country, are desperate for higher quality education options. The NYC Charter Center reports that in the Bronx alone, more than 25,000 families applied for just over 9,000 available seats in Bronx charter schools.

Even so, in an attempt to curry favor for his failed presidential bid, NYC Mayor Bill DeBlasio angrily attacked charter schoola as part of his opening statement at the 2019 annual forum of the nation’s largest teachers union, the National Education Association. “I hate the privatizers and I want to stop them,” he said. “Get away from high-stakes testing, get away from charter schools. No federal funding for charter schools.”

These are not idle threats. DeBlasio, along with teachers unions and many Democrat elected officials, have consistently blocked legislation that would lift the numerical “cap” on new charter public schools in New York City. This all but ensures the nearly 16,000 Bronx parents on a waitlist for charter public schools will be forced to enroll their kids in district public schools that have been failing their community for generations.

The education of children

Why is there so much irrational opposition to low-income families who want nothing more than the opportunity to choose a high-quality public school for their child?

In his richly researched new book, Charter Schools and Their Enemies, author and economist Thomas Sowell poses the dilemma in this way: “Even the most successful charter schools have been bitterly attacked by teachers unions, by politicians, by the civil rights establishment and assorted others. How can success be so unwelcome?” Sowell answers this question with painstaking detail, revealing that these forces are really focused on protecting “adult vested interests in traditional unionized public schools,” and are committed to “limiting the exodus of students from traditional public schools to public charter schools.”

Throughout the book, Sowell attempts to correct falsehoods and distortions that anti-charter advocates keep repeating in hopes that lies ultimately become accepted truths. For example, given the frequent tendency for DeBlasio and allied opponents to falsely accuse charter schools of attempting to privatize education, Sowell offers a definition of these schools:

Public charter schools are public schools not created by the existing government education authorities, but by some private groups who gain government approval by meeting various preconditions set by the authorizing agencies. These agencies issue charters enabling these schools to operate as public schools eligible for taxpayer money and to enroll public students who apply.

On more than one occasion, Sowell feels he must italicize and remind the reader that “schools exist for the education of children,” not to “provide iron-clad jobs for teachers, billions of dollars in union dues, or a captive audience for indoctrinators.” Sowell reasonably establishes a singular general principle for evaluating any proposed reform to the education system: “How is this going to affect the education of children?” In the words of Sowell, “those who want to see quality education remain available to youngsters in low-income, minority neighborhoods must raise the question, again and again, when various policies and practices are proposed.”

Struck by the accomplishments of charter public schools, Sowell is compelled to envision the potential of the American system if all public schools adopted the same practices that have driven charter schools’ success. But he raises one important note of caution: “The implications of [charter schools’] existing achievement can be a game-changer in the field of education—to the extent that facts are known and heeded.”

Herein lies Sowell’s central aspiration and basic plea for fairness: If more people can “know and heed” the overwhelming evidence detailing the positive impact of charter schools on the education of children, perhaps more poor and minority students can have access to a “good education which is their biggest opportunity for a better life.”

That is why Sowell so meticulously sets up a data framework to contrast the achievement levels of students in district public schools to “truly comparable” students in charter public schools. Sowell uses the results of the 2018 New York State Education Department tests in math and English language arts, which are administered to all students in grades three through eight—whether those students are in district or charter public schools. He drills down even further to ensure he only compares students who share the same grade, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic characteristics. Finally, he compares district public school students and charter public school students who are “co-located,” meaning their respective schools share the same building, and often even the same floors.

Applying all of these filters, Sowell identifies a significant sample of 23,000 district and charter public school students, all being educated in the same buildings. Sowell’s Appendix alone has more than one hundred pages of charts detailing the sixty-five co-located charter public schools in the city and how their respective students performed on state tests compared to similarly situated district public school students.

The results of this truly “apples-to-apples” comparison are impressive. While not every charter public school outperformed its co-located district public school in every grade, the difference was decisive in an overwhelming number of cases. For example, in the five buildings in which they were co-located with district public schools, a majority of the students in the KIPP charter network passed the 2018 math exams in twelve of their fourteen grade levels. By contrast, among the students in the traditional public schools sharing the same buildings, a majority passed the math exam in just one of their twenty grade levels.

Sowell’s analysis of charter school prowess is hardly an outlier. Just recently, Harvard professor Paul Peterson published a comprehensive, longitudinal study, finding:

Student cohorts in the charter sector made greater gains from 2005 to 2017 than did cohorts in the district sector. The difference in the trends in the two sectors amounts to nearly an additional half-year’s-worth of learning. The biggest gains are for African Americans and for students of low socioeconomic status attending charter schools.

The success of charter schools cannot be denied.

Fighting enemies, within and without

Yet, to anti-charter advocates, these facts are to be ignored, distorted, or discredited because the success of charter public schools has been achieved through unallowable means. And while the purveyors of these attacks remain an ominous and external threat to charter schools, there is a new development coming from within the sector that has the potential to undermine both the legacy and future of charter schools. Sowell refers to a “particularly striking—and perhaps dangerous—institutional change” occurring within leading charter schools to “promote anti-racist practices” that are much more likely to diminish the importance of individual student effort, sow greater racial division, and worst of all end up perpetuate disempowering stereotypes of Black Americans.

Perhaps a letter by Dave Levin, founder of the KIPP network, best exemplifies these new dangers. He recently apologized for how, over twenty-five years, he “as a white man ... and others, came up short in fully acknowledging the ways in which the [KIPP] school and organizational culture we built and how some of our practices perpetuated white supremacy and anti-Blackness.” Towards this end, KIPP has retired its longtime slogan “Work Hard, Be Nice” because “working hard and being nice is not going to dismantle systemic racism ... it suggests being compliant and submissive ... and it supports the illusion of meritocracy.”

It is not clear where these revelations from charter leaders are going. How can the practices that have yielded unbelievable gains for low-income, Black, and Brown children symbolize the perpetuation of white supremacy? These newly woke forces from within the charter sector threaten to inflict an even greater wound than the external oppositions that charter schools have now weathered for more than two decades. One has to hope they will not.

With formidable opponents attacking from the outside and corrosive ideologies now festering from within, it is a wonder the charter sector has managed to survive at all. Yet, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, “charter schools serve 3.3 million students in America, and there are five million more who would attend a charter school if space were available.”

It is this part of the story—the David versus Goliath nature of the charter sector—that I wish Sowell had also chronicled. The enemies of charter school may be formidable, but the battle is not lost. There are successful strategies the sector has deployed to push back against the gargantuan opponents arrayed against it.

I would know. For the last decade, I was CEO of a network of charter public schools in the heart of the South Bronx and the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Our faculty had the solemn responsibility to educate more than 2,000 students—primarily low-income, Black, and Hispanic kids—whose parents chose our schools because they want their children to develop skills and habits that would help them achieve a better life, becoming the agents of their own uplift. I am now designing Vertex Partnership Academies, a new network of character-based, International Baccalaureate high schools that will open in the south Bronx.

Leaders in the charter sector do not take on the grueling work of launching these schools because we are anti-union or ruthless “privatizers.” We are motivated by families who do not have time to sit around while their child languishes and wait for the public school system to transform itself. What do you tell the twenty-two-year-old mom of a five-year-old who needs a great elementary kindergarten class for her child, today?

In the current moment of riots and protests demanding racial justice, rather than embarking on a White guilt trip down memory lane, charter leaders must stress their legacy of accomplishment, particularly in educating low-income, Black, and Hispanic students. And we have to elevate the voices of parents themselves as a force that unions and other anti-charter advocates cannot dismiss or ignore any longer. Our families do not believe their children are doomed to be shackled by the horrors of America’s legacy of slavery. That is why they crave the ability to choose the good schools that middle- and upper-income families take for granted.

When the charter sector faced an existential threat in New York in 2013, leaders mobilized nearly 17,000 parents, aunts, grandmothers, and other family members to march across the Brooklyn Bridge wearing shirts that said “We Fight Inequality” and “My Child, My Choice.” A few months later, caravans of busses with 11,000 family members trekked to bitter cold Albany to advocate for school choice.

Parents, mostly Black and Brown, argued that hundreds of thousands of kids were trapped in poorly performing schools, and that low-income families like them must be given the option to choose charter schools. Even Democratic politicians, who now had concentrations of high-performing charter schools within their districts, publicly signaled their support. Those efforts led to amazing legislative victories for increases in per pupil funding, permanent public funding for leasing private facilities, and more flexibility in how charter schools could recruit and professionally develop our faculty.

Perhaps Sowell desired for Charter Schools and Their Enemies to paint the most dire picture of the sector, lest we forget how fragile our hard-fought victories are. But, on behalf of the 16,000 children in the South Bronx, and the more than 5,000,000 families nationwide who are waiting for their child to find a spot in a charter school, let’s hope his sequel publication is entitled “How Charter Schools Overcame Their Enemies”—all while focusing on the education of children.

Editor’s note: This was first published by Law & Liberty.