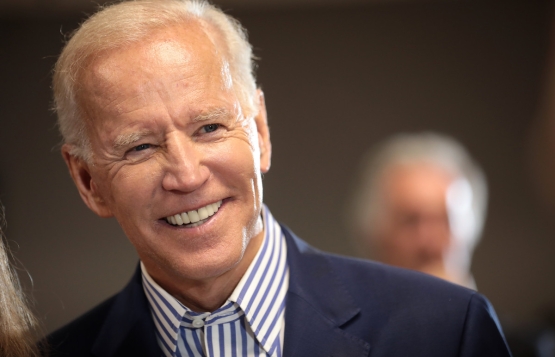

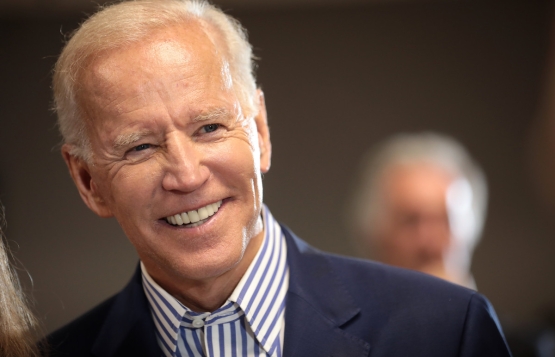

Biden’s soft touch might be the only hope for schools in blue districts to reopen

What will it take for President Biden to make good on his December promise to reopen a majority of U.S. schools within his first one hundred days?

What will it take for President Biden to make good on his December promise to reopen a majority of U.S. schools within his first one hundred days?

What will it take for President Biden to make good on his December promise to reopen a majority of U.S. schools within his first one hundred days? Especially given his comments at Tuesday’s town hall that the goal is to get K–8 students back in person five days a week, and that he thinks we can get “close to that”?

Biden himself says that more money is essential to pay for ramped-up testing, PPE, better ventilation, and additional staff. That’s why his massive Covid-19 relief bill includes billions for schools. But if a dollar deficit were the real issue, we’d have long since seen more progress in getting kids back into classrooms, given the significant cash infusions already included in the past year’s several relief packages. Or consider California, where Governor Newsom’s offer of $2 billion in extra money for schools willing to reopen was met with widespread shrugs. Note, too, that schools have been open all year—full time—in about a quarter of districts nationwide, many in red states not known for showering public education with cash.

The president’s offer of yet more money, then, should be seen for what it really is: part of a diplomatic offensive to help teachers and their unions feel good about getting on board the reopening train.

That’s because the fundamental challenge in getting schools reopened isn’t financial or technical. We know how to keep kids and adults safe, as shown by schools all over the country and world that have been doing this successfully since the fall. Make everybody mask up and wash their hands frequently, adjust routines to avoid large assemblies, and do whatever’s practical to improve air flow and ventilation. As multiple studies from the CDC and elsewhere have found, such mitigation efforts make schools much safer places for kids and adults than their surrounding communities.

No one can promise perfection. Some children and adults will get sick. But we must balance that against the real and significant harm to our children caused by keeping them at home. There’s the massive learning loss, especially among students of color. But there’s also the mental health strain of isolating at home, including a troubling increase in youth suicides, plus serious concerns about increased child abuse that’s less likely to be reported.

So what’s really keeping more schools from reopening? Some teachers are sincerely scared to death, and don’t trust their administrators to keep them safe. (Would you trust a big-city district bureaucracy to keep you safe?) They need to know that leaders understand their concerns and take them seriously.

Thankfully, our empathizer-in-chief seems to grasp this. President Biden has been meticulously careful not to get edgewise with teachers or their unions throughout his campaign, the transition, and his early days in office. First Lady Jill Biden, herself a member of the National Education Association, built further goodwill by inviting the heads of the two national teachers unions to the White House for a photo op. His administration has been careful not to take sides in intensifying battles at the local level between Democratic mayors and recalcitrant unions, especially in hot spots like Chicago, San Francisco, and Philadelphia. And the new guidance from his CDC provides cover to concerned teachers, as well, given its cautious recommendations about reopening schools when community spread remains high, as remains the case almost everywhere.

This soft touch is a stark contrast with the previous team, which was already at war with public school educators when President Trump and Education Secretary DeVos demanded in early autumn that schools reopen, despite surging Covid rates. That naturally led unions to harden their positions, especially in the deep-blue cities and states where they are most powerful—which are also the places that disproportionately serve our most disadvantaged students.

With the departure of Trump and DeVos, President Biden had a chance to restart the reopening debate. His strategy appears to focus on hugging the teachers and their unions in public, while pressuring them to come along in private. This is not unlike what union presidents themselves are trying to do, as Mike Antonucci points out—showing solidarity with their members while not trying to appear too unreasonable to other stakeholders.

Biden’s patience and behind-the-scenes cajoling appear to be paying dividends. Teachers in Chicago recently agreed to return to schools, a major win given the size of the district and its union’s reputation as among the most militant in the nation. San Diego teachers just approved a deal, and the District of Columbia, Baltimore, and New York are also slowly bringing kids back, too.

Still, that leaves millions of students in purgatory, learning remotely full time in cities including Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Los Angeles. When the president’s Covid-19 relief bill passes, as seems increasingly likely, that should provide yet more cover for unions to come on board.

If the Biden team is able to make good on his vow to reopen schools, it won’t be because of big bucks in his new relief bill, nor the new guidance from the CDC. It will be because he’s made good use of his office, his empathy, and his diplomatic skills to make teachers feel respected and safe enough to come back to class.

Barely a day goes by without another story reporting the negative effects of keeping schools closed. The issue is far more pronounced in blue states, where local teacher unions continue to stand in the way of reopening despite the entreaties of President Biden’s aides and their clumsy kowtowing to union brass. Meanwhile, Republicans have been having a field day with all of this, leveling accusations at the new administration and their union allies of putting politics ahead of kids.

As the trading of barbs continues, what’s easily lost is that kids are already back in school in much of the country, or are headed in that direction, thanks in large part to red states and their GOP governors. In states with a more purplish hue, it’s taken a bit more negotiation, as in Ohio where the state’s governor is using the carrot of teacher vaccinations as a stick to make schools reopen. The question now is how to engender similar movement in deep blue states with strong unions when they don’t want to get to yes. Other than hoping for Biden to become more assertive with his union friends, is there anything reformers can do about it?

Three recent articles, taken together, help to provide an answer. The first was written by AEI’s Rick Hess and published in The Dispatch. According to Hess, the school reopening debate is a case study in Politics 101:

In any political dispute, whether it concerns sugar subsidies or military base closures, decisions tend to favor organized interests and inertia tends to carry the day. Right now, that favors those who want schools closed. Changing this state of affairs requires more than impassioned pundits and a handful of frustrated parents (writes the pundit and parent). It requires changing the cost-benefit calculation for educational leaders.

It’s hard to overstate Hess’s point as the debate over reopening schools—at least when it comes to the science and the moral imperative—has largely been won. Schools should be open. But political progress has been elusive because of the unions’ savvy (e.g., AFT’s head honcho has been all over the news) and the palpable fear of Covid-19 that has taken hold of many educators and families alike.

The second was a deep dive into union activism penned by my friend Derrell Bradford in the pages of Education Next. Deftly tying multiple story threads together, Bradford argues that we’re in the throes of a de facto national teacher strike with a bonanza of a windfall on the line:

Biden’s proposed tripling of federal Title I education dollars annually, to about $48 billion from the current $16 billion, would allow for a significant expansion of local teacher headcount, bolstering union dues while circumventing the need to raise increased funds for teacher pay at the local level where the political and financial costs would be more sharply felt. These policy outcomes are quite possibly sufficient incentive to keep schools closed until they are enacted.

The key word here is “incentive.” The unions are playing a high-risk, high-reward hand of poker, where a loss of public good will is a possibility. But in looking at their cards, they see a lavish, once-in-a-lifetime political payoff that wouldn’t have been possible without the pandemic.

The question of incentives is also the thrust of the third piece, authored by the National Review’s Ramesh Ponnuru. With his trademark Vulcan dispassion, Ponnuru makes the case that bashing the unions does little if anything to help get students back into classrooms:

But what else did we think the teachers unions would do? They have a better reputation than other unions because most people value teachers and what they do for kids. Most of us know a teacher who is overworked and underappreciated. But the unions themselves don’t exist to pursue the interests of children, or the common good. Their job is to represent their members.

The unions’ current focus on what appears to be a minuscule risk to the safety of their members may be unreasonable. But looking after their safety is one of their leaders’ core responsibilities. Making sure children learn isn’t. That’s not an opinion about their character; it’s a fact about their incentives.

Casting aspersions at the unions is a favorite pastime among reformers—one that I’ve admittedly indulged in—but Ponnuru raises a valid point about which side is behaving rationally in this debate. Both Hess and Bradford suggest as much, too, in outlining the institutional, professional, and strategic reasons unions have for slow rolling reopening.

With millions of students now approaching a full year without in-person instruction in any form, reformers would do well to come together on how to alter the stakes in this game. This means governors have to step up and lead courageously by setting clear expectations for opening schools. Yes, it’s much harder in blue states, but not impossible. To wit, Virginia’s governor recently called on all schools to reopen next month. Districts quickly fell in line behind the plan. Rhode Island, a blue state in its purest form, is an even better example of vision and resolve. If every governor shared Gina Raimondo’s moxie, states would have thrown open their schoolhouse doors long ago.

What else might break the logjam in blue states? The ineptitude in cities like San Francisco could whet an appetite for change if current conditions are allowed to persist. Frustrated and angry parents in particular have strained old alliances and galvanized the space for new ones. The best thing reformers can do in this situation is to use a light touch and allow families to drive the conversation, letting the chips fall where they may. Still, it remains to be seen whether that will be enough to move the needle. The only thing for certain is that, from the get go, the unions deployed a coherent strategy and have a vested interest in preserving the current state of play.

Perhaps the biggest buzz in education-reform circles these days, and among the philanthropies that pay for such things, is community empowerment and community control. Instead of welcoming ideas, programs, strategies, and schools devised by distant experts, policy wonks, do-gooders, and state leaders—all of whom tend to be white and privileged—the traditional power relationships should be reversed, advocates say. Those who are supposed to benefit from reforms should now be in charge of deciding what needs to change and also be in charge of the institutions engaged in such change. Instead of “being helped” they should have ownership. Reforms should be “made with us, not to us” is often heard. Rather than thanking their benefactors, community members and leaders should decide what needs to be done, determine how it should be done, and direct the doing of it.

The “communities” referred to, in almost all these instances, consist of people of color—and sometimes members of other long-disempowered and discriminated-against populations, kept down over the decades by rich, powerful elites because said elites are greedy, entitled, condescending, and loath to give up any privilege or power.

It’s past time, we are told, to begin viewing education reform through the other end of the spyglass and to upend the power structures and leadership structures that have kept that from happening.

The impulse for all this is totally understandable and laudable—more on this below—and for a lot of people it’s not new at all. For as long as I’ve known and revered Howard Fuller, he has been making the same case for the same reasons. Outside the education realm, one can point a lot further back to Saul Alinsky, for example, Frederick Douglass, Dorothy Day—and Karl Marx, too, for that matter.

Its recent re-application to K–12 education reform in the American context, however, is coming from some less familiar places.

Consider the Walton Family Foundation’s new five-year strategy, which “prioritizes...championing community-driven change to ensure the foundation’s work reflects the voices and needs of communities in which it works,” as well as “diversity, equity and inclusion in the grants the foundation makes and the voices it engages.” Consider the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s K–12 program emphasis on “partnering” with schools and networks of schools rather than devising and promulgating programs of its own devising. Consider the foundation-supported City Fund’s “aim to invest in organizations led and informed by people of color and historically marginalized families.” Or the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s premise that “those impacted by policy issues are often best equipped to drive solutions and hold those in power accountable.”

Turning to the receiving end of ed-reform philanthropy, we find—among many examples—a determined move within the National Association of Charter School Authorizers to place “communities at the center” of future charter authorizing. NACSA CEO Karega Rausch wants his organization to “center this work in the hopes and aspirations and needs that local communities actually have for their kids.”

It’s worth focusing on charter schools in part because, as I’ve written many times over the years, they’ve almost always been community-centric if not necessarily creatures of their communities. I’m no fan of what’s happened to most locally-elected school boards, captives as they so often are of employee interests rather than reflecting the will of the larger community. And I have long described charters as a bona fide reinvention of “local control” in education as it was meant to be. Even now, more than two decades in, for all the hoopla about big charter networks, two-thirds of U.S. charter schools remain local institutions. Some are free-standing single-site schools—we used to call them “mom and pops”—while others are small, one-city networks including some great schools that Fordham is proud to authorize in Ohio.

They’re local, they’re very much in and of their communities, and like all schools of choice, they’re subject to the ultimate in local control: families that don’t like what they’re doing are free to walk out the door and down the street to enroll their children in a different school.

Yet for the most part, these and many other “local” charters don’t entirely match what today’s power-shifting reformers seem to have in mind. Though the schools themselves are attended mostly by the Black and Brown youngsters for whose benefit they were created, oftentimes their leaders, board members, rainmakers, funders, and/or a fair number of their teachers are mostly White and/or from out of town and/or individuals who grew up in middle class families, went to elite colleges, and do not themselves reside in the ‘hood.

As an authorizer, let me note, we at Fordham are aware that no community is monolithic—a reason we support school choice in general, as it allows families living on the same block to pursue differing education priorities, needs, and values. As an authorizer, we also have to ask whether “community control” of the schools in our portfolio would mean we could never pull the plug on a really weak one. Pretty much every school, regardless of its track record, is beloved by its students, families, and neighborhood. In the charter world, however, being liked isn’t supposed to be enough.

Crusaders like Fuller understand that and deal well with the complexity. But it’s complicated. And for the most part, at least until recently, the relatively privileged—and not-from-the-neighborhood—population of a many charter-school founders, leaders, teachers, and board-members has not been a problem for philanthropists, whose own demographics are not exactly community-centric, or for the larger ed-reform movement. It and its funders have sought to do what they saw as the right thing for needy kids, which meant respecting expertise and welcoming the energies of TFA types who would devote a couple of years to the inner city before going into finance or technology. It also meant cultivating elected officials regardless of race, party, or ideology, and certainly cultivating big-time philanthropy, even if the money came from people with names like Gates, Walton, Zuckerberg, Carnegie, and Broad.

Why the push to change that today? The immediate motives, goals, and concerns at work here are entirely understandable, worthy, even noble. The country has been forcefully, vividly, and painfully sensitized to the depredations of racism, paternalism, sexism, injustice, and inequity, even as it has also struggled under the burdens of an awful pandemic and a seemingly endless epidemic of sick politics. It’s time, a growing number of people appear to have concluded, for yesterday’s reformers to quit making decisions for those they set out to “help.”

Also coursing through our culture and politics these past few years, though mostly coming from a different direction and manifesting itself in ways most ed-reformers and philanthropists find appalling, is populism: the conviction among a lot of Americans that they, too, have been left out, manipulated, and disrespected by elites, and deprived of their fair share of just about everything. They, too, want to be in charge.

Please at least recognize the parallels!

More next week, if you can stand it.

In a time when the “traditional” K–12 educational experience is going through upheaval and reconfiguration into myriad pandemic-influenced shapes and sizes, it is important to note that many of the so-called innovations students are experiencing are not new. Sudden shutdowns of school buildings? Been there. Asynchronous lessons? Old hat. Fully-remote learning? So last century. Even the hybrid learning models that are burgeoning at the moment are entirely precedented.

A recent research report looks at the academic outcomes achieved by one such model: the four-day school week. Created for non-emergency reasons and opted into (and out of) willingly by school districts for decades, the effects of this long-standing, untraditional model on student achievement could give us some idea of how the Covid-19 version might fare in serving students.

While Oregon has allowed districts to choose to offer a four-day school week since the mid-1990s, Oregon State University researcher Paul N. Thompson focuses in this study on the period between 2005 and 2019, during which time the number of schools using such a learning model grew, peaked, and declined. That peak number comprised 156 schools across the state. Schools opting in obtained a waiver from the state’s department of education for the amount of required school days and were required to provide a minimum number of hours of education instead. The structure of the four-day week—specifically, what, if any, work is required of students on the off-day and how it is counted toward the hours requirement—is generally up to the schools to determine. It is not described in this report, but a previous analysis by Thompson and colleagues noted that nearly half of districts surveyed closed their buildings entirely for academics on the off-day. In Oregon particularly, the off-day was widely used for athletics and other extracurriculars, many of which counted toward the state’s physical education requirements.

The baseline academic data under study—student achievement on math and reading standardized tests for grades three through eight on the Oregon Assessment of Knowledge and Skills test—showed a marked difference. Analyzing a total of 3,172,170 individual test scores from 690,804 students, and applying a variety of demographic and other controls, Thompson found that math test scores were between 0.037 and 0.059 standard deviations lower, and reading scores were between 0.033 and 0.042 standard deviations lower, for students in four-day schools versus those in five-day schools. Schools with four-day school weeks also had a smaller percentage of students meeting proficiency thresholds in math (60.7 percent compared to 64.7 percent) and reading (68.1 percent compared to 70.9 percent). This amounts to around seven to ten fewer students scoring proficient in four-day schools than in five-day schools, depending on student-body size. English language learners fared worst of all subgroups in terms of achievement declines, but interestingly, students with special needs actually bucked the trend and scored very slightly higher as a group in four-day schools than in five-day schools. These data are clear and compelling, but could there be other factors at work than simply the change in schedule?

Because a number of schools moved from four-day to five-day schedules and vice versa during the study period, Thompson was able to use a difference-in-differences research design to determine that the reduction in face-to-face instructional time explained a majority of the test score declines observed in four-day models. And for schools that moved from a four-day to a five-day week, a one-hour increase in weekly time in school led to a 0.018 standard deviation increase in math achievement and a 0.006 standard deviation increase in reading achievement for their students. These are small increases in themselves, but have the potential to compound to greater significance over multiple additional hours.

Noting that many Oregon districts reported adopting a shorter week due to financial concerns, Thompson also looked at the potential trade-off between cost savings and achievement. Oregon districts were required to submit per-pupil spending details related to the shortened schedule to the state, and he compared this to similar data from studies in other states. A $1,000 per pupil cost savings realized by a shortened week yielded an achievement loss of between 0.094 and 0.189 standard deviations. Compared to other traditional cost saving approaches elsewhere (larger class sizes, reductions in force, etc.), the academic achievement losses experienced in Oregon were the same or lower than most, but still a net academic loss.

Many schools across the country have adopted four-day school weeks out of pandemic necessity. At the same time, we are seeing evidence of very alarming academic achievement losses. Data from pre-crisis times indicate that the two things are inextricably and negatively linked. The dire achievement plunges we are seeing today are magnitudes greater than this report shows, indicating sustained and exponential harm to student learning. We likely will not see achievement rise again until we can ensure more time in face-to-face education for our students. But even that will just be the start of the uphill battle.

SOURCE: Paul N. Thompson, “Is four less than five? Effects of four-day school weeks on student achievement in Oregon,” Journal of Public Economics (December 2020).

Back in May 2020, The U.S. Department of Education had to issue guidance clarifying that, yes, schools and districts were still required to provide language instruction services for English learners (EL) during remote learning. The need for this reminder is disheartening, given that, for many ELs, school closures mean they are missing out on opportunities to hear and speak English on a regular basis, which compounds the extent of their potential learning loss.

Even during business-as-usual schooling, the needs of EL students—despite being the fastest growing student population in K–12 schools today—often garner far less attention than enduring learning gaps suggest that they are owed. Although 55 percent of teachers have at least one EL in their classroom, only 2 percent of teachers are actually certified to teach ELs, and eleven states have no requirement for EL-only instructors to have any kind of specialist certification or endorsement.

Nor has EL instruction been given priority in general education teacher preparation. Only California and Texas, states with the highest percentage of EL students (19 and 18 percent, respectively), specifically mention EL-relevant content in their requirements for teacher candidates.

If this is the case, then we’d better hope we have some pretty darn strong EL-friendly instructional resources in our classrooms. But do we? A recent Rand Corporation report by Andrea Prado Tuma, Sy Doan, and Rebecca Ann Lawrence draws on data from 5,978 teachers who participated in the 2020 American Instructional Resources Survey to analyze their perceptions of whether the primary instructional materials they used during the 2019–20 school year met the needs of ELs, as well as the extent to which teachers modified the materials to meet the needs of their EL students.

Their findings seem to indicate that, yes, most teachers do believe that their instructional materials meet the needs of their EL students. Seventy-eight percent indicated that they either “strongly agreed” or “somewhat agreed” with this statement. Teachers who taught in majority-EL classrooms, however, were much more confident in their materials than teachers who taught in classrooms where less than 50 percent of their students were ELs. The researchers hypothesize that perhaps this indicates that teachers in more heterogeneous classrooms have a more difficult time finding appropriate instructional materials that meet the needs of both English speakers and English learners, while EL-majority classrooms were able to more closely tailor their materials to the needs of ELs.

Teachers serving a high percentage of ELs were also exceedingly more likely to report making extensive modifications to their main materials to better meet the needs of EL students, especially when they believed these materials were falling short. In contrast, only 6 percent of teachers who taught fewer than 10 percent ELs reported that they engaged in substantial modification. Teachers who had an EL-certification were significantly more likely to make extensive modifications to better meet their EL’s needs—although this difference became non-significant when it was taken into account that such teachers were more likely to teach in majority-EL classrooms.

The researchers use the findings of this study to make somewhat vague suggestions for stakeholders. Teachers in heterogeneous classrooms probably need better EL instructional materials, they say, and probably need PD on how to modify their existing materials.

But one substantial limitation prevents the authors from offering more substantive policy recommendations. Because the survey data don’t account for students’ learning outcomes, it’s impossible to get a clear picture of whether instructional materials are actually meeting EL needs. Nor do the data allow us to answer perhaps even more important questions: Are teachers, most of whom have little formal training in EL teaching, able to accurately determine the quality of their instructional materials with this population in mind? And, if so, do they have the skills necessary to appropriately modify insufficient materials to better meet EL needs?

Although this study provides a jumping off point for thinking about the needs of EL learners and their teachers, further research is needed so that schools, teacher preparation programs, curriculum manufacturers, and policymakers have a clearer understanding of how classroom assets and issues affect the support and education of our country’s growing EL student population.

SOURCE: Andrea Prado Tuma, Sy Doan, and Rebecca Ann Lawrence, “Do Teachers Perceive That Their Main Instructional Materials Meet English Learners' Needs? Key Findings from the 2020 American Instructional Resources Survey,” RAND Corporation (2021).

On this week’s podcast, Bibb Hubbard, founder and president of Learning Heroes, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss how to leverage parents’ newfound awareness of their children's academic struggles during the pandemic. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines whether in-person schooling contributes to the spread of Covid-19.

Dan Goldhaber, Scott A. Imberman, Katharine O. Strunk, Bryant Hopkins, Nate Brown, Erica Harbatkin, & Tara Kilbride, “To What Extent Does In-Person Schooling Contribute to the Spread of COVID-19? Evidence from Michigan and Washington,” NBER Working Paper #28455 (February 2021).

If you listen on Apple Podcasts, please leave us a rating and review - we'd love to hear what you think! The Education Gadfly Show is available on all major podcast platforms.

“Kentucky is set to be the first state to finish vaccinating teachers.” —EdWeek