There are, generally speaking, two ways to report students’ performance on tests. One is normative, and it compares a student’s performance to his peers. The second is criterion, and it compares a student’s performance to learning standards, indicating grade-level proficiency and is independent of peers’ test performance. American students have, as readers know, suffered from significant learning loss. Since the pandemic, students’ scores on criterion-based assessments like state summative tests and NAEP have dropped broadly across the country. Ironically, this drop in performance has caused norm-based assessments to award higher marks to lower performance, relative to pre-pandemic levels.

This is a problem when normative tests are relied upon to gauge the state of learning today and how much we’ve recovered from that learning loss. This is because norms have no relationship to content, standards, mastery, or proficiency. For example, current norms of a widely used national assessment indicate that, while its norms describe learning trends, “they provide no guidelines about necessary growth or achievement relative to any established academic standards.”[1] Another widely used assessment reinforces the difference between norms and standards: “Test norms are best used when decisions are being made that require you to compare a student’s score to that of other students. When you want to determine if a student is at risk of not meeting standards, [criterion-based] benchmarks should be used.”

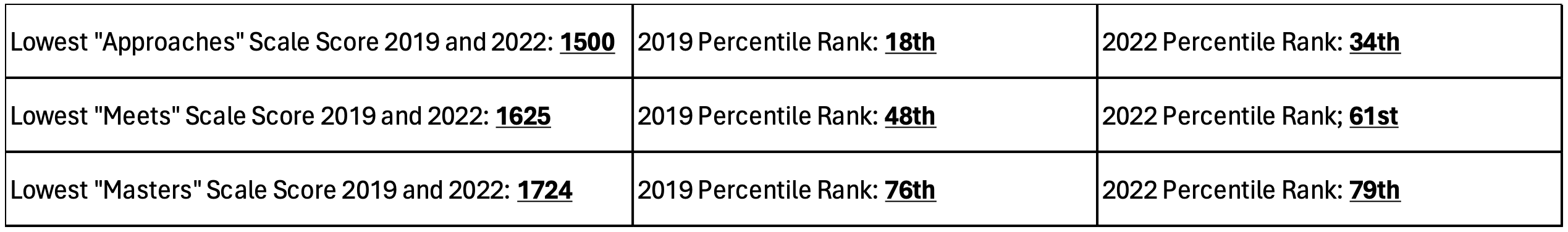

Consider Table 1, which shows criterion and normative scores on the Texas’s STAAR in 2019 and 2022, its primary standardized assessment for grades 3–11. The test did not substantively change over those three years, yet a student in 2022 who receives the same criterion score (e.g., Approaches, Meets, or Masters) on the STAAR test as a student in 2019 will receive a higher normative score. For example, in math, a fifth grade student who scored 1625, or the lowest score within the “Meets” category, would receive a normative score of 48th percentile in 2019 but a 61st percentile in 2022. The higher normative score has nothing to do with student learning; it is because students now are under-performing compared to their pre-pandemic peers.

Table 1. Texas STAAR criterion and normative scores in 2019 and 2022[2]

Consider, too, an illustration of how this problem plays out in classrooms today. Imagine it is 2019. “Ben” receives a 58 percent on his math test—an F. Fortunately for Ben, his teacher decides to grade on a curve, a norm-based practice. Ben is relieved when he receives a B+ on his test instead. We can consider Ben’s original grade—an F—to be his “criterion score” because it is based on how many grade-level learning standards he has mastered—learning standards that educators believe will prepare students for success in school and, ultimately, in life.

The grade Ben receives—a B+—is normative because it is determined by comparing how well Ben performed relative to his classmates. Calculating the curved score is entirely unrelated to what one might assume primarily determines grades—knowledge and mastery of math content. Similarly, norms like percentile ranks are calculated with zero information about grade-level standards, expectations, content, proficiency, etc.

Now, imagine it is 2024. “Gail” receives a 58 percent—an F—on the same math test that Ben took in 2019 and with the same teacher. Unfortunately, due to pandemic-related unfinished learning, the rest of Gail’s class is even less prepared than their cohorts prior to the pandemic. As a result, Gail’s classmates score lower than Ben’s class in 2019. The teacher grades on a curve again, and Gail is reassured to receive an A- as her final grade.

So Gail receives a higher normative score than Ben, despite the fact that both Ben and Gail know the exact same amount of information and possess the same skill level regarding the same topics, demonstrated on the same test with matching scores of 58 percent.

There are number of possible implications of using norm-based information, but three are especially noteworthy. The first is that it can lead to the under-identification of intervention needs. Norm-based percentile ranks play a prominent role in identifying students who need additional supports to realize success in school (via MTSS/RTI programs). For example, in many cases, students below the 40thpercentile receive additional instructional supports. For students with the same level of mastery of reading or math (criterion metrics), fewer would be identified as 40th percentile or lower, and fewer students would receive additional supports. This challenge can largely be addressed by ensuring normative scores are not used in isolation but always paired with grade-level or criterion metrics.

The second is inflated parental perception of student learning. It’s been widely reported that (1) there is something amiss when attendance is down, proficiency is down, and grades are flat, and (2) parents are largely uninformed about the fact that most kids are not operating at grade level. So, if Ben’s or Gail’s parents want to know if they are operating at grade level, where will they turn? Grades may not always be an accurate reflection of grade level mastery. State summative test scores are not available until after the school year ends. So they will likely turn to the most widely used interim assessments nationally: i-Ready, Star, or MAP Growth. Each of these interim assessments produces an abundance of information about scale scores and learning trends, but, in my experience, parents typically only remember the normative percentile rank as the answer to “how is my child doing” and “is my child on grade level”? Why? Because percentile ranks are familiar and easy to understand. That narrow view of student learning creates the illusion that students are outperforming pre-pandemic America—and that is just not true. (Some of pre- versus post-pandemic differences between normative and criterion data are outlined in a recent WestEd publication.)

Third, if new post-pandemic norms are going to create all these complexities, educators, administrators, and parents find themselves in a challenging catch-22. Pre-pandemic norms are not accurate nor applicable anymore because we are in a “new normal.” The implementation of new norms can create complexity and confusion, and yet new norms do provide the best and clearest picture of where students are. i-Ready will update its norms for fall 2024, and we encourage all other assessment programs to follow suit..

There are, however, a couple ways to mitigate the operational and perceptional challenges. One, normative data need to be paired with criterion data, and the two data points need to be used together to avoid misunderstanding and misinterpreting of where students are. And two, more broadly, data in education should ultimately represent and reinforce the idea that ambition and high expectations are foundational to significant and sustained learning impact. Elevating Gail’s grade because everyone else is doing less well doesn’t support the primacy of ambition and high expectations that we need in American education, both for the sake of each student and for the sake of our communities and country.

[1] Yeow Meng Thum and Megan Kuhfeld, “NWEA 2020 MAP Growth: Achievement Status and Growth Norms for Students and Schools,” NWEA, July 2020, page 84.

[2] Texas Education Agency (TEA) Texas STAAR Achievement Levels, Raw Scores, and Percentiles: https://tea.texas.gov/student-assessment/testing/student-assessment-results/raw-score-conversion-tables; detailed 2019 TEA Tables: https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/accountability/academic-accountability/performance-reporting/2019-staar-apr-5-math-rsss.pdf; detailed 2022 TEA Tables: https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/accountability/academic-accountability/performance-reporting/2022-staar-5-math-rsss.pdf.