Editor’s note: This is the second part in a series on teacher evaluation reform. Part one recalled how teacher evaluation became a thing. This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

Today, I’ll summarize the heyday of this movement, which lasted roughly six years from 2009 to 2015. It hit the rocks as quickly as it began—and not necessarily because it didn’t “work,” so to speak. Here’s how it happened.

What were we thinking?

There was broad support across the political spectrum for improving teacher evaluation. But it’s most deeply associated with that cast of characters called ed reformers, of whom I’m one. Our movement, sometimes portrayed as consisting of alumni from Teach For America’s first fifteen years, but better understood to include a multi-generational amalgam of frustrated civil rights organizations, maverick district administrators, and assorted malcontents, shared a set of beliefs that animated their work. Others may put it more eloquently, but my description of our thinking in the early 2000s would go something like:

- America’s achievement gaps are shameful—and fixable. We were exceptionally optimistic about the potential of every child to succeed academically. Poverty could not be accepted as determinative. Low performance stemmed from educational neglect and low expectations.

- Our optimism about children was combined with extreme cynicism about the systems that schooled them. These were the villains. They watched kids fail and then blamed them for it. They defended practices like “last in, first out” layoffs that may have been preferable to adults but were demonstrable harmful to students.

- There was scant margin for error. As blue collar jobs disappeared, kids would be punted into a thankless economy and forced to scrape for a comfortable profession. Failure at school would mean failure in life.

- Instead of fixing individual schools—or even districts—we needed to focus on whole systems. Think bigger. Stop tinkering around the edges. Don’t just raise student performance, eliminate the gaps entirely—to zero.

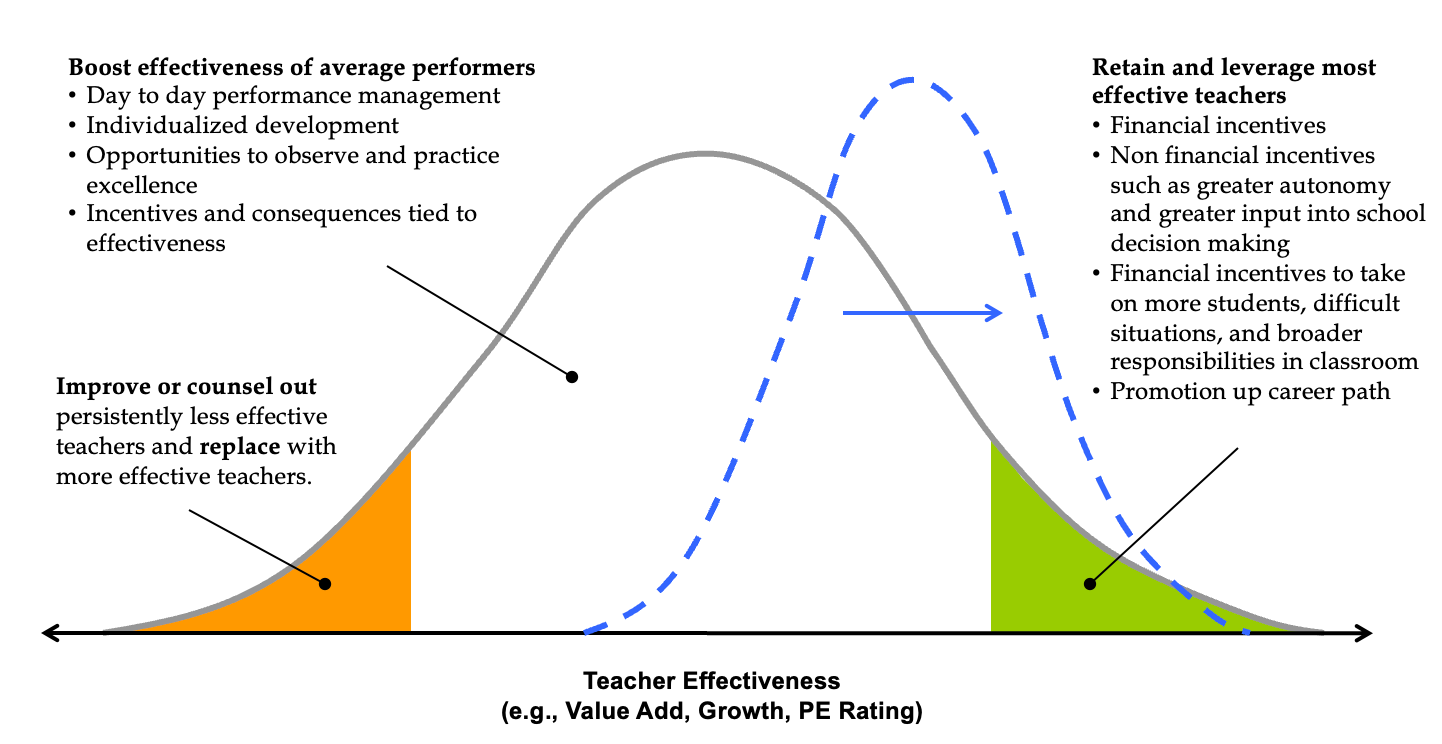

- The data were clear. Acting on the differences in effectiveness between teachers—by improving or dismissing the lowest performers and retaining the highest performers—offered the greatest potential to raise student achievement of any available lever. From heart, we quoted excerpts from research papers like “Having a top-quartile teacher rather than a bottom-quartile teacher four years in a row could be enough to close the Black-White test score gap.”

- Systems wouldn’t take this lying down. They were made to resist, to wait out. Any short-term change would be washed away overnight like a sandcastle.

I’m oversimplifying only slightly in saying we felt we had been presented with a math function. There were some low-performing teachers. Past patterns suggested they were unlikely to improve. If they exited the profession and were replaced by typical new hires—and if, at the same time, more of the highest-performing teachers were retained for more years—achievement would rise significantly. The question was whether we had the courage to do it.

What did we advise districts and schools to do?

New evaluation systems needed to yield accurate results and hold up when challenged in due process. Unions—which had expressed openness to modernizing evaluations—made clear that the evaluations must be objective. That was their term. New approaches couldn’t rely on the perfunctory classroom observations of principals, who were seen by the unions as keepers of personal vendettas. Standards had to be the same from one classroom and school to the next.

Reformers accepted this challenge with an excess of enthusiasm. In the process, I suspect we also took the bait. To meet the unions’ specs while achieving the goal of differentiating good teaching from bad, we got technocratic.

You can see this in a document we published at TNTP about a year after The Widget Effect. Teacher Evaluation 2.0 was a set of specific recommendations for redesigning evals. Summarized briefly:

- Annual evaluations. If we’re serious about improving instruction, a biannual (or even less frequent) process doesn’t deliver sufficient feedback.

- Clear, rigorous expectations. The bar should be excellence rather than minimally acceptable compliance, e.g., this lesson has a written objective, as some observation protocols required.

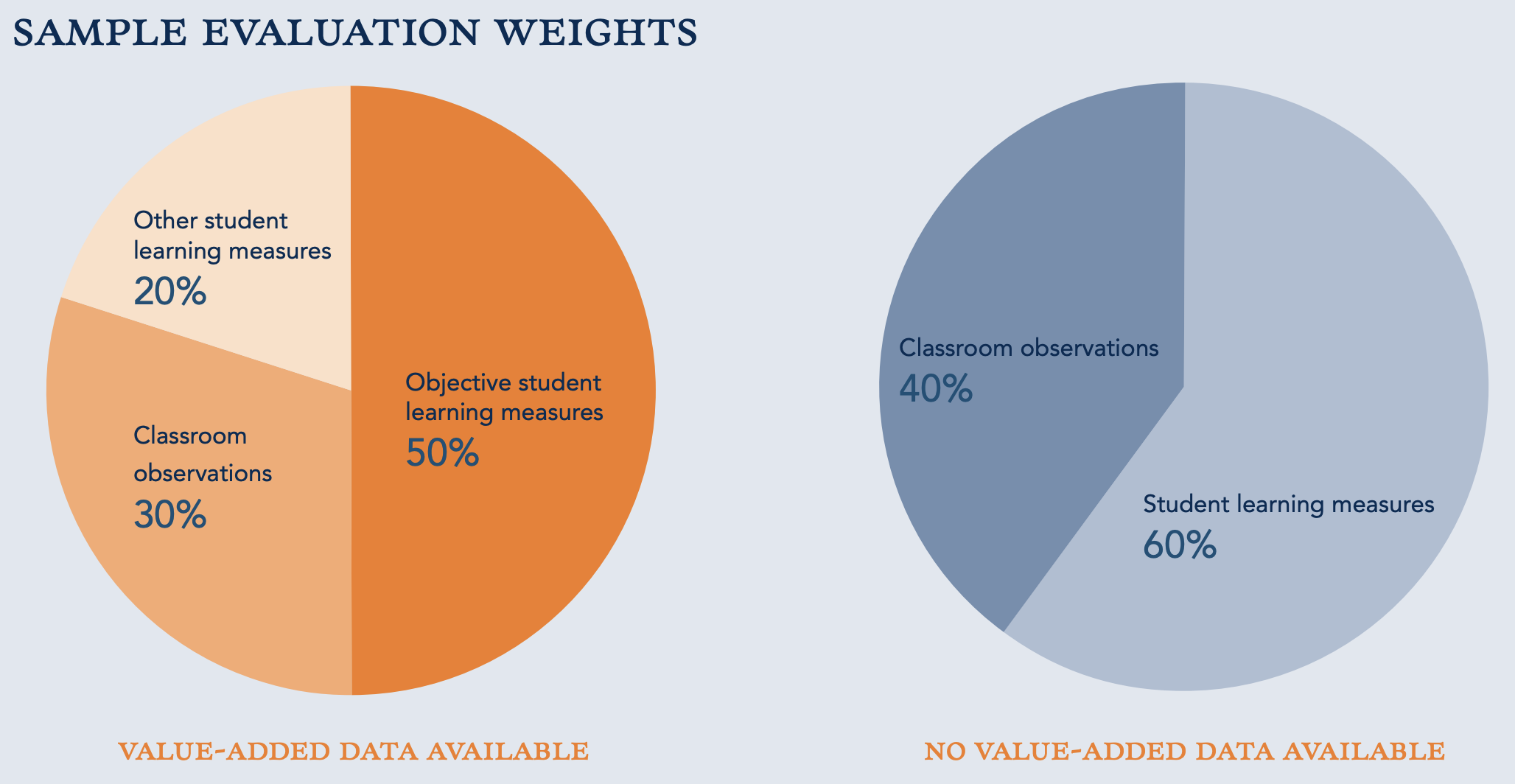

- Multiple measures. This was a biggie. The idea of using more than one data source was not controversial, but we suggested placing more weight on objective measures of student achievement—like growth in test scores—than observations. It was a radical departure from the way teachers had been evaluated. We’ll get into this in greater detail before this series is done, I promise.

- Multiple rating categories. Some districts used a simple binary of satisfactory or unsatisfactory. A teacher was A-OK or fired. We recommended four or five levels to create usable differentiation.

- Regular feedback. Evaluations should not depend on a single point in time where the principal breezes through with a clipboard. They should be frequent enough to be fair and drive improvement.

- Evaluations should inform decisions. Not just dismissal for low performers, but also pay advancement for top performers, opportunities to become a lead teacher or coach, and protection for top teachers against being laid off during hard economic times (in the wake of the real estate crash, layoffs were a very real threat).

With these design recommendations handy and snowballing momentum around evaluation, the stage was set for states to overhaul their systems in their quests for Race to the Top funds.

Away we went

Whoa boy, did things take off.

By 2016, forty-four states passed teacher evaluation legislation. The number of states requiring consideration of evaluation ratings when conferring tenure rose from zero—and that’s not a joke, pre-2009, you got tenure as long as you weren’t fired by a certain deadline—to twenty-three.[i]

In 2009, only four states required student outcomes to be the preponderant component of a teacher’s evaluation. In 2015, the number had grown to sixteen. The number of states requiring outcomes to count for some part of the final rating increased from fifteen to forty-three.

The success of evaluation reform on paper—in the law—was remarkable. How about on the ground? Much more complex. And less successful.

A group of early movers received constant press attention. The highest profile belonged to D.C. Public Schools, which rolled out their system, called IMPACT, for the 2009–10 school year. The state of Tennessee, one of the first winners of Race to the Top, piloted its system in 2010–11 and fully deployed it in 2011–12. Also, beginning in 2009–10, the Gates Foundation underwrote evaluation overhauls in three districts—Hillsborough, Florida; Memphis, Tennessee; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—as well as a collection of California charter networks.[ii]

These systems deserve a deep dive of their own, but we don’t have space to do it here. For our purposes, you mainly need to know that D.C.’s and Tennessee’s efforts were effective by most definitions. Independent research verified that student achievement improved, teachers responded to the new evaluations by getting better, and high performers were retained while low performers left at higher rates.[iii]

The Gates districts did not succeed—particularly because enthusiasm for implementing the new systems waned and teachers still generally received very high ratings.

In just about all cases, though, the political blowback against early adopters was fierce.

Along with that heat, two factors slowed implementation of new evaluations more broadly.

The first was the transition to the Common Core State Standards, which most states had committed to adopt. New standards meant new assessments with more rigorous definitions of a “proficient” student. It was not possible to calculate a student’s annual growth using their performance on one type of test in year A and a totally different test in year B. Many states paused consideration of student learning in teacher evaluations while the tests were in transition.[iv]

The second was rising tension around teacher dismissals. This subject received tons of public discussion in the early-mover districts and states. Were teachers really going to be fired? In significant numbers?

In some cases, the answer was yes. Central Falls, Rhode Island, fired all the teachers at its underperforming high school in February 2010. Somewhat ironically, this decision was not predicated on evaluations of individual teachers. It was a blanket move to clear the way for a school turnaround. Teachers were not given any due process. When President Obama embraced this tough love approach, he opened a rift with teachers unions and cemented the notion that improving schools meant firing teachers.

In 2010, the first results from D.C.’s IMPACT system came in. The Washington Post’s headline was “Rhee dismisses 241 teachers in the district.”

As the public perception of evaluation reform became more associated with firing low performers and less with recognizing and rewarding great teachers, political support declined. Teachers unions dropped their neutral/open stance and actively opposed new teacher evaluations. It happened relatively quickly.

In 2014, AFT President Randi Weingarten retreated on the use of student performance and publicly embarrassed the Gates Foundation by refusing to accept its money. Just a few months later, the National Education Association called on Obama’s Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, to resign for his support of changes to teacher evaluation and tenure.

While facing these defections from the left side of the political spectrum, the evaluation coalition had the same problem on the right. There were multiple drivers, but a major one was the Obama Administration’s offer to states of waivers from NCLB sanctions in exchange for adoption of its favored policies—including evaluation. Conservatives felt that the program amounted to micromanagement of local districts. Before long, Republicans were against just about everything Obama was trying to do in education—even some stuff they’d favored a few years prior.

The wave that propelled teacher evaluation to the top of the education agenda dissipated. By the time most states completed their pauses and began to officially implement their new laws, there wasn’t much heft behind them. In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo, who had been a hawk on teacher evaluation, reversed his position in 2015 and called for reducing the emphasis on student tests after families began opting their children out of them. Most states similarly backed off.

In an eye-opening 2017 paper titled Revisiting the Widget Effect, Matt Kraft and Allison Gilmour reviewed twenty-four states that had adopted teacher evaluation reforms and reported that less than 1 percent of teachers were being rated unsatisfactory in nearly all of them. After so much drama about teachers getting fired, few were.

A 2023 paper reported that, nationally, evaluation reforms had no effect on student achievement.

It didn’t take long for teacher evaluation to go from the hot new thing to declared a failure.

Why? What were the missteps? What have we learned from them? Those questions will require a post of their own. Next time, we’ll wrap up this series by going there.

[i] NCTQ did a great job tracking all of the policy changes in real time. Their 2015 yearbook is available here. Chad Aldeman also unpacked it for a 2017 retrospective in Education Next.

[ii] There are many more early movers, some of whom took big risks to implement their systems and got notably good results. I don’t mean to shortchange them here by omission. Cincinnati, New Mexico, Newark, and Dallas are just a few.

[iii] In D.C., researchers found that IMPACT achieved “substantial differentiation in ratings,” pressure on low performing teachers to improve. When teachers departed, “DCPS has been able to replace low-performing teachers in high-poverty schools with teachers who are substantially more effective.” D.C.’s performance on national tests improved dramatically. In Tennessee, a major study concluded that “evaluation reform contributed to student achievement gains and that evaluation reform operated to improve student achievement through two mechanisms: teacher development and strategic teacher retention.” Tennessee’s ranking on national tests also improved quite a bit. Lynn Olson did a nice write-up for FutureEd here. You can read about the disappointing results for Gates-funded sites here.

[iv] More than a few advocates felt that pushing for new standards and new teacher evaluations concurrently was too much—that the standards should have come first. Then, after teachers got used to them, go for the evaluations. If you wonder how we responded, I invite you to re-read the description of our thinking at the top of this post.