Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2024 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to answer this question: “How can policymakers and practitioners radically reduce chronic absenteeism—at least below pre-pandemic levels and preferably much further?” Learn more.

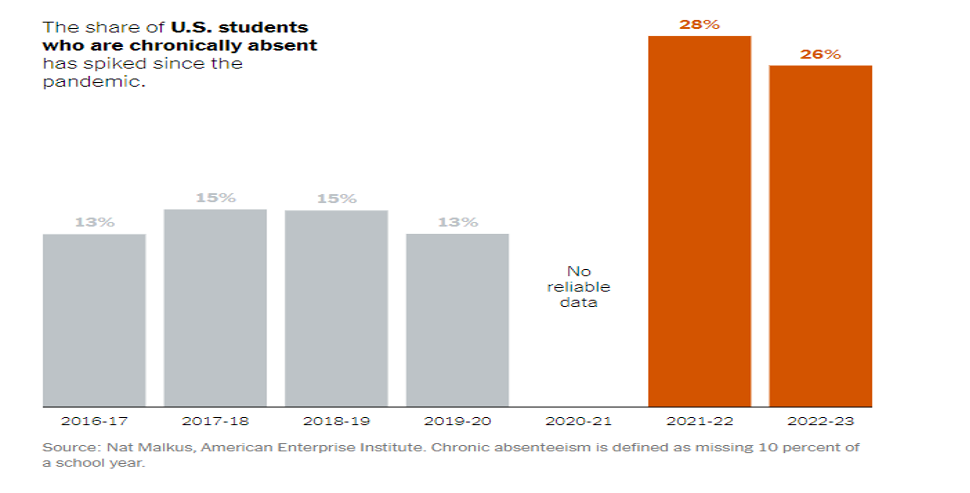

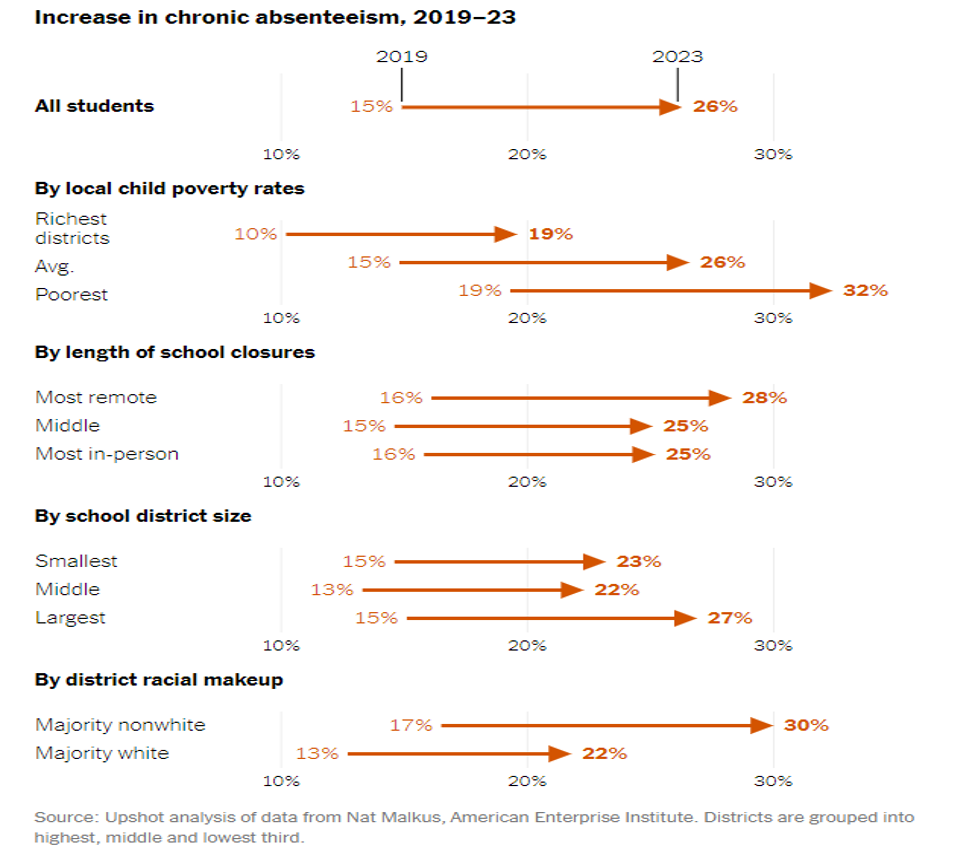

The fact that chronic absenteeism rates—defined as missing 10 percent of a school year—continue to rise, especially after the pandemic has been well established (Mervosh & Paris, 2024; Appendix I). That these increases cut across students’ achievement levels, district sizes, modes of instruction (in-person versus online), poverty, and households is equally well-documented (Mervosh & Paris, 2024; Appendix II). Nevertheless, there are sustainable, and promising, interventions that have been shown to noticeably reduce chronic absenteeism. I will briefly discuss some of these effective approaches below.

Woodbridge Elementary in Catonsville, Maryland, reduced its chronic absenteeism rate from 28 percent in 2021–22 to just over 9 percent in 2022–23. According to the report by Linda Jacobson in The 74, the school accomplished this, first and foremost, by recognizing and prioritizing student attendance. As a result, the school understood the patterns that increased absences, such as early-release days, and addressed that by offering an after-school program and wavering the $10 fee for students who have demonstrated absenteeism. This was followed by sustained monitoring and the result speaks for itself.

In the 2015–2016 school year, prior to Covid-19, 50,000 public school students in Connecticut public schools (9.6 percent of the student population) were chronically absent. Predictably, this was further exacerbated by the pandemic in the 2019–2020 school year. The Learner Engagement and Attendance Program (LEAP) was inaugurated in April 2021 to address this pressing chronic absenteeism problem, which was now worsened by the pandemic. The program essentially involved conducting well-coordinated, meaningful home visits with students identified as chronically absent in fifteen districts in the state of Connecticut. In the spring of 2022, LEAP was evaluated by researchers from Wesleyan University, Central Connecticut State University, and the University of Connecticut using mixed-methods analyses. Results indicated statistically significant findings in increases in attendance rates directly related to the LEAP intervention. Specifically, there was an initial 4-point increase during the first month of this intervention for students exposed to it. The increase persisted steadily to an average of about a 7 percentage point increase by the summer of 2021, rising to about a 15 percentage point average increase “in the 6 months or more after treatment” (CCERC, 2022, p. 8). Even more noticeable were the remarkable gains by Hartford Public Schools where the attendance rates improved by almost 30 percentage points (ibid.).

Although many schools and school districts utilize home visits as a strategy to moderate student attendance issues, the remarkable results of the LEAP should warrant deeper understanding. Therefore, the question then becomes: How were home visits done differently in the LEAP case? The study identifies the following specific attributes of this strategy:

- Personalized, dynamic support: Dependent on family’s needs

- Continued training and support for the visitors

- A process of collaboration (e.g., determining caseload assignments)

- Home visitor fluency in the language used in the home

- Commitment to establishing connections with families

- Collaborative advocacy for students (e.g., parents, home visitors)

(ibid.)

The district leaders in LEAP identified the opportunity to collaborate and learn from other districts and the flexibility of implementation, particularly the use of funds afforded by the state of Connecticut to schools as the main reasons for its success.

The home visitors and the families reported the following benefits:

- Improved family-school relationships

- Increased student attendance

- Increased student engagement

- Increased student achievement

- Increased feelings of belonging

- Increased access to resources for families

- Increased expectations of accountability

- Greater gratitude and appreciation

(ibid.)

It is noteworthy to point out that, according to the study report, home visits in this program could be at a student’s home or over Zoom or phone. Unsurprisingly, significantly larger impacts were reported for true home visits (i.e., where the visitor physically went to the student’s home) as opposed to the “visits” done via Zoom or phone. It is reasonable to assume that the six characteristics listed above are more likely to be attained when a visitor physically visits a student’s home. There is a level of personalization that this affords that is difficult to replicate with Zoom or phone. Equally noteworthy is the fact that effects of the LEAP treatment on English language learners (ELL students) in the targeted schools were significantly below—only about half as large as non-ELL students. This may be worth further research.

Regarding challenges, one is funding. Specifically, the late arrival of funding delayed the project to a degree. Staffing, including but not limited to hiring and training the right personnel for the work, was also a challenge. Sustainability must be addressed because the leaders believe that a two- to three-year commitment will be more helpful overall for all stakeholders. Other challenges included teacher resistance, family resistance, and fearful families (as a result of immigration status).

In conclusion, it is important to highlight the key ingredients of effective interventions that have been empirically shown to substantially reduce chronic absenteeism. Research shows that when these components are integrated with fidelity into attendance-improving interventions in schools and school systems, chronic absenteeism can be drastically curtailed. Early identification and intervention that can immediately address and prevent chronic absenteeism from snowballing; mentoring programs, family engagement initiatives, and personalized support strategies; collaborative efforts involving schools, families, and communities; targeted interventions based on individual student needs and circumstances; and prioritizing and creating a supportive and inclusive environment that encourages regular attendance and student engagement. Finally, continuous monitoring and evaluation of intervention programs are necessary to assess their impact and make necessary adjustments for long-term success. (Eklund et al., 2020.)

Appendix I

Adapted from: Mervosh, S. and Paris, F. (2024, March). “Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere,” The New York Times.

Appendix II

Adapted from: Mervosh, S. and Paris, F. (2024, March). “Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere,” The New York Times.

References

Center for Connecticut Education Research Collaboration (CCERC), (2022). An evaluation of the effectiveness of home visits for re-engaging students who were chronically absent in the era of covid-19. Retrieved from: https://www.attendanceworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CCERC-Report-LEAP_01_24_2023_FINAL.pdf

Connecticut State Department of Education (2017, April). Reducing chronic absence in Connecticut’s schools: A prevention and Inter vention Guide for Schools and Districts. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/SDE/Chronic-Absence/Prevention_and_In tervention_Guide.pdf?la=en

Eklund, K., Burns, M. K., Oyen, K. A., DeMarchena, S. L., and McCollom, E. M. (2020). Addressing chronic absenteeism in schools: A meta-analysis of evidence-based interventions. School Psychology Review, pp 1-17. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345485326_Addressing_Chronic_Absenteeism_in_Schools_A_Meta-Analysis_of_Evidence-Based_Interventions

Jacobson, L. (2024). Report: Schools won’t recover from COVID absenteeism crisis until at least 2030. The 74. Retrieved from: https://www.the74million.org/article/report-schools-wont-recover-from-covid-absenteeism-crisis-until-at-least-2030/

Mervosh, S. and Paris, F. (2024, March). Why school absences have ‘exploded’ almost everywhere: The pandemic changed families’ lives and the culture of education: “Our relationship with school became optional.” The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/03/29/us/chronic-absences.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap