Helping students recover from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the other crises of the past year is likely the greatest challenge that most of today’s educators will ever face. It will take extensive time, skill, and collaboration between leaders, teachers, staff, and families. And it will look different from community to community—and even from school to school.

One key question is how instructional leaders might sequence the implementation of various pieces of a recovery plan, such as the one recommended in The Acceleration Imperative, and how to bring them into a coherent whole. See below for thoughts about that, and a model student schedule that indicates what all of this might look like in practice.

Recommendations

- Put the basics in place before adding new elements, especially high-dosage tutoring. Adopting and helping teachers implement a high-quality curriculum is job number one. Many elementary students, especially those in high-poverty schools, will need extra help to recover from the loss of instructional time related to the pandemic. Done right, high-dosage tutoring shows great promise in helping such students return to grade level. But doing it right means integrating tutoring with regular classroom and small-group instruction and using the same high-quality instructional materials in all cases. Successful high-poverty schools that already had evidence-based instructional strategies and high-quality instructional materials in place before the pandemic might be ready to start integrating tutoring into their programs. But other schools have to walk before they can run.

- Build a positive and supportive school climate. Many students will return to school with significant mental-health needs because of the significant trauma associated with the pandemic, the economic downturn, and America’s reckoning with racial injustice. This will lead some of them to want to act out or shut down at school. But by building strong relationships, ensuring school policies and practices reflect and engage diverse families, and setting high, common, school-wide expectations for behavior and academic achievement, schools can help students feel safe and optimistic and keep them focused on learning.

- Don’t bite off more than you can chew. The only recommendations that will help students thrive are ones that are implemented thoughtfully, with fidelity, and with attention to detail. Aim for quality over quantity, and save some steps for later.

- Make teachers’ jobs doable. Consider asking teachers to team up via “departmentalization,” for example with one teaching English language arts and another teaching math to both of their classrooms. That may be especially helpful at schools that are implementing new high-quality curricula, given that each teacher would have fewer subjects to master. Alternatively, schools with several years of experience with high-quality instructional materials might consider “looping,” where teachers stay with their current students and follow them into the next grade in the fall to maintain strong relationships. All schools, districts, and networks should also consider focusing on “priority” instructional content, as identified by Student Achievement Partners.

- Embrace external support. Most schools should get help from professional learning organizations with expertise in the high-quality curricula their district or network has chosen. Such curricula come with embedded assessments that produce actionable data. External support organizations can help schools and teachers make good decisions around mid-course corrections.

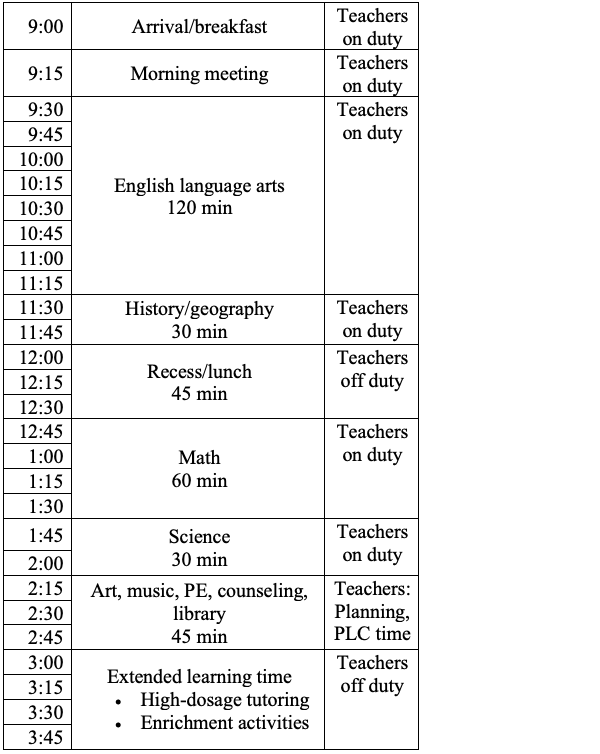

Sample student schedule

A school’s precise schedule will depend on the time requirements for its chosen curriculum, along with various constraints, such as collective bargaining agreements and transportation logistics. Those specifics aside, here’s one example of a schedule that makes room for all of the elements discussed in The Acceleration Imperative plan.

Reading List

Betts, F. (1992). How Systems Thinking Applies to Education. Educational Leadership, 50(3), 38-41.

Bryk, A., Gomez, L., Grunow, A., LeMahieu, P. (2105). Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bryk, A., Sebring, P., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., and Easton, J. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Deming, W.E. (2018). The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education (3rd. Ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fleming, K. (2021). I-Flex: A New Teaching Modality for Post-Pandemic Recovery. Core Education.

Leonard, J. (1996). The New Philosophy for K-12 Education: A Deming Framework for Transforming America’s Schools. Milwaukee, WI: ASQ Quality Press.

Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Scholtes, P. (1998). The Leader’s Handbook: Making Things Happen, Getting Things Done. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.