Earlier this month, Michael Petrilli wrote about America’s top-quartile students making gains from 2009 to 2019 over their already high baseline—in math, reading, and science—and our lower-quartile kids declining from their already low baseline. As Joanne Jacobs observed, “The smart got smarter.” Importantly, this happened before Covid complications.

Why? Petrilli lists possible causes: Maybe it’s non-school issues like kids becoming screen zombies, the Great Recession harming families, or assortative mating. Maybe it’s school-based issues like funding cuts, looser accountability, and Common Core–aligned curricula.

These are great hypotheses, to which I would add two more, specifically for math.

1. Pedagogically, there’s been a change since 2009 in what happens during a typical math class, particularly in elementary schools.

Without getting bogged down in the never-ending Math Wars, it’s safe to say a common approach for a fourth grade teacher used to be to teach one lesson to all the kids in the class. The teacher would pull struggling students into the conversation, which might slow down the overall pace. Advanced kids were often bored.

Over the last ten years, however, elementary teachers increasingly assign all the students in the class to work independently on computers in the room.

This mirrors broader trends. PISA 2018 data show 71 percent of American students using laptops in class, compared to 37 percent globally. And that’s only gone up. In fact, even from pre- to post-pandemic, we see a rise here. A Christensen Institute 2021 survey of 1,042 teachers found a general rise in all manner of adaptive learning tools from 6 percent to 30 percent from before Covid to after.

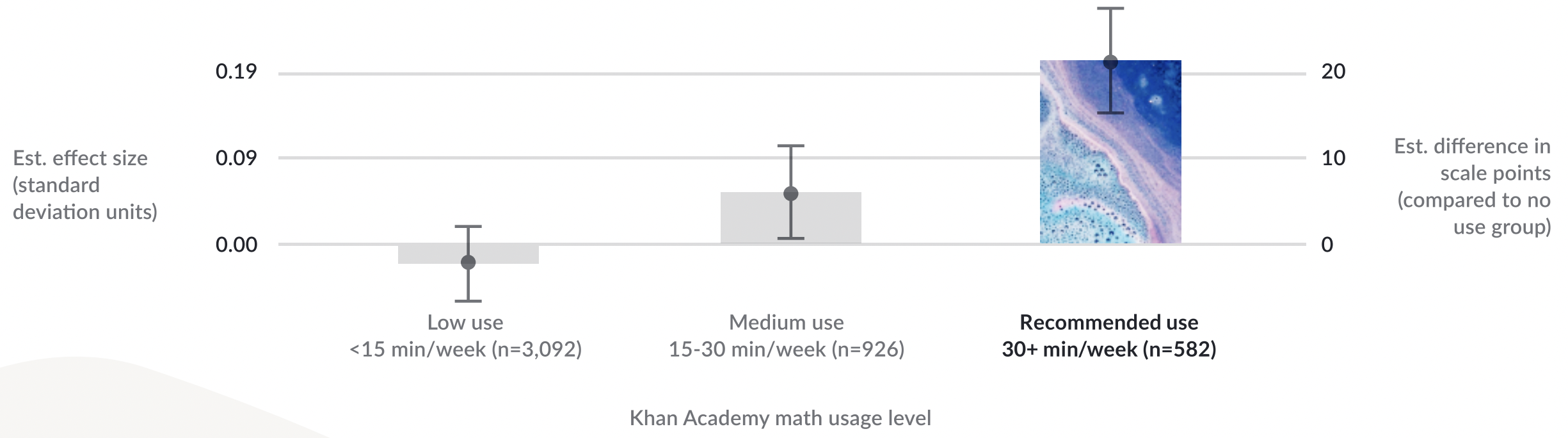

The best empirical evaluations tend to show gains for the more disciplined kids who actually do the math problems—but that, often, the typical student doesn’t do much. For example, in a 2018 study conducted in Long Beach, California, kids who used Khan Academy for thirty minutes per week made nice gains. That’s the pretty blue and pink rectangle on the right in the figure below that comes from the study.

Figure 1. Association between use of Khan Academy and 2018 Smarter Balanced Assessment math scores, compared to students with no use

Unfortunately, that was 582 kids. Another 3,092 kids did less than fifteen minutes per week. Those are the kids on the left side of the graph, in the small grey rectangle. They saw zero gains (even slightly negative). So the most diligent kids in the study pulled away from the other kids.

Maybe NAEP is capturing this change to elementary school math class.

Certainly it’s plausible for teachers to circulate and give personal human attention to strugglers while more advanced students are learning on the software. How often does that happen in real life? We don’t know. But we can probably all agree that, at minimum, advanced students are now more able to learn math at a slightly faster pace. Moreover, just to be precise, math software often works particularly well with the unusual student who is more diligent than their peers (i.e., lots of effort into the assigned problems) yet also mathematically weaker at baseline. But that’s not the typical use case, where a stronger math student is also more likely to spend more minutes trying hard on the math software.

My own hypothesis is that strugglers can lose the plot entirely online—that the “hints” from the software aren’t yet advanced enough to get kids “unstuck.” But that day will come! The software will improve. For now, though, sometimes strugglers just shut down when stuck and simply stop doing problems (or if teacher nudges them to try, they randomly click to nominally complete the assignment).

2. Second, private tutoring in the U.S., especially in math, has surged since 2009.

Economist Edward Kim tackles this topic in his 2021 study. He writes:

From 1997–2016, the number of private tutoring centers grew steadily and rapidly, more than tripling from about 3,000 to nearly 10,000.

Second, the number and growth of private tutoring centers is heavily concentrated in geographic areas with high income and parental education. Nearly half of tutoring centers are in areas in the top quintile of income.

So perhaps private math tutoring—not what does or doesn’t happen inside schools—drives some of these NAEP learning gains for the top quartile. Empirically, we know high-quality tutoring helps kids. People like Susanna Loeb and Kevin Huffman vie to bring more of it to public schools. Yet these programs face significant operational obstacles.

Consider this analogy: Pediatricians encourage parents, even (and especially) poorer parents, to buy fruits and vegetables for their kids. Docs realize fresh food is expensive, that there are food deserts without access, and there are other limiting factors. Yet they still try to nudge parents towards better nutrition expenditures.

I wonder if the pediatrician-vegetable approach is worth considering for private math tutoring. Should we seek to convince more middle- and lower-income families to buy tutoring for struggling math students as a complement to our efforts inside schools?

As best I can tell, nobody is telling poor parents what the rich parents already know (and do), that math tutoring is akin to eating your vegetables. Even programs that offer to make private tutoring free are under-used, like one in New Hampshire. Why? Parents with less social capital don’t quite grasp that you can like your public school yet still want to add tutoring on top.

On the other hand, we don’t have the same high-quality research data about private math tutoring as we do for in-school tutoring. Think about it. Tutoring in schools can be randomized. A math center like Kumon or a neighborhood tutor can’t easily randomize their customers, so they have no true control group for evaluation purposes.

I hope to find a way to solve that and launch some new research about private tutoring quality! If it turns out to be good for families, maybe encouraging greater consumption of it can be one tool in the broader effort to help our nation’s strugglers.