Interdistrict open enrollment is the biggest school-choice program that practically nobody ever mentions, perhaps because it’s less conspicuous and more socially acceptable than its cousins, private school vouchers and public charter schools. But it could be doing so much more for the children of Ohio.

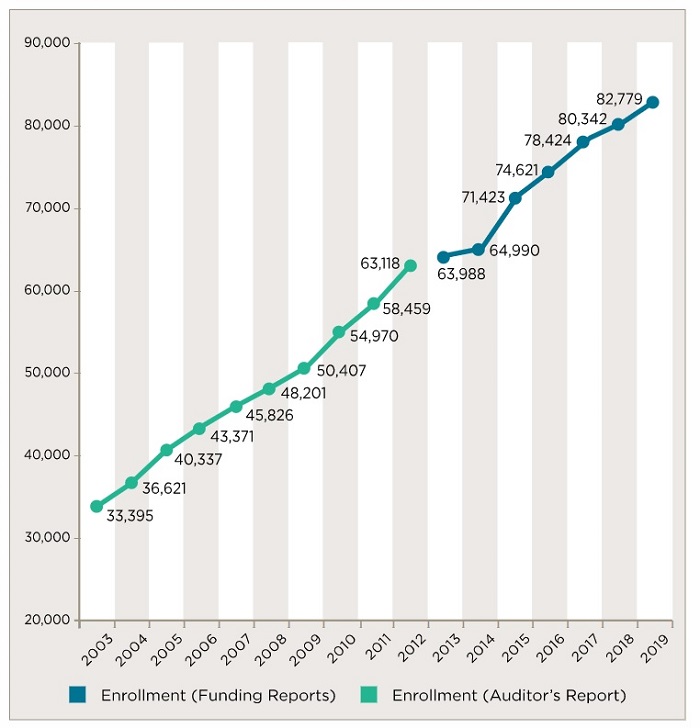

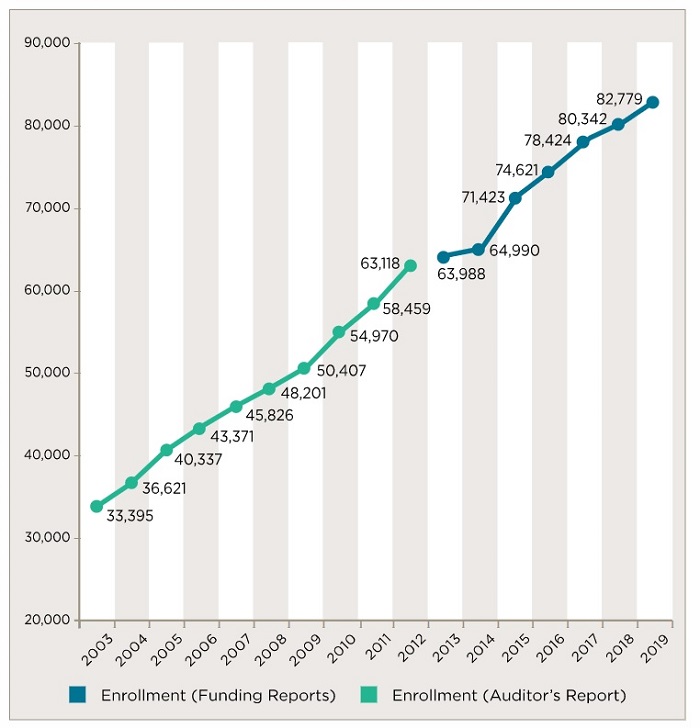

Essentially, open enrollment allows students to register and attend classes in a school district other than the one where they live. It’s popular, too. As the graph shows, more than 80,000 Ohio students availed themselves of the opportunity in 2018–19.

Figure 1: Annual student participation in interdistrict open enrollment 2003-2019

Don’t blame us at Fordham for its relative obscurity. Open enrollment crops up all the time in the Ohio Gadfly, and three years ago we published a report by professors Deven Carlson and Stéphane Lavertu that analyzed its academic impact. They found that open-enrolling over multiple years is linked to test-score gains, albeit modest ones, and that Black open enrollees especially benefit. Open enrollment throughout high school also boosts the odds of on-time graduation.

Earlier this month, a Fordham policy brief recommended that Ohio shift away from a punitive, top-down school accountability system to one focused on transparency and school choice. As part of that, we proposed requiring every district in the state to participate in open enrollment, which is not the case today. Currently, each local school board decides whether its district will take part and, if so, whether it will admit students from any Ohio district or only from adjacent districts. Each participating district also decides how many transfer students it can accommodate and establishes a fair process for admitting them (it can’t cherry pick). That’s pretty much it.

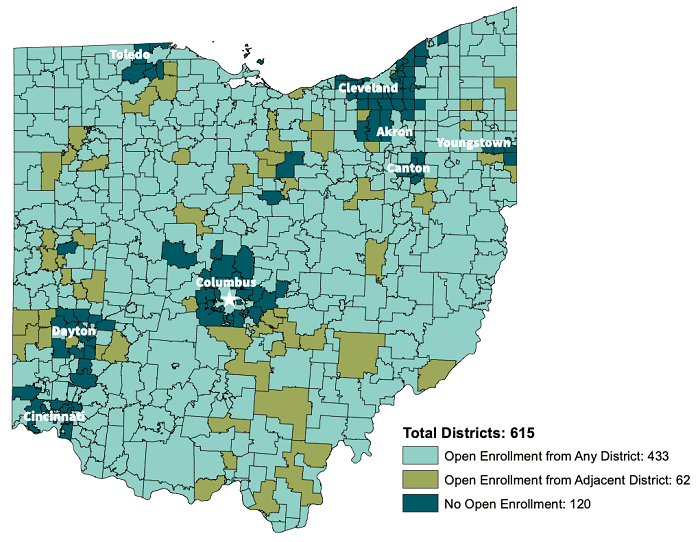

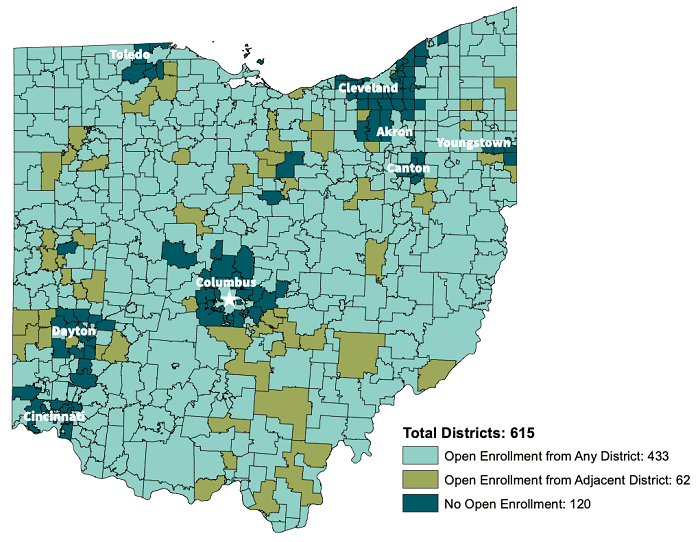

Given how many districts participate, that process must not be too stressful. In recent years, 70 percent of districts accepted students from anywhere in the state and another 10 percent welcomed pupils from neighboring districts. But participation isn’t what most people would call equitable. Figure 2 helps visualize it:

Figure 2: Ohio school districts by open-enrollment status 2013-14 school year

While the map’s a few years old, the picture it shows is true today: Across huge swaths of the state, nearly every school system participates. But look again and you will see that, around Ohio’s major cities, it’s a different story. Their choice-hostile neighbors, mostly prosperous suburban school districts, are at the crux of Fordham’s recommendation. Consistent with the research of Carlson and Lavertu, we believe that Ohio’s most disadvantaged students—many of whom live in cities surrounded by districts walled off to open enrollment—could benefit from access to more public school choice.

It’s easy for districts to opt into open enrollment. The question is why so many suburban districts, one of which I live in, don’t roll out the welcome mat.

A legitimate objection to open borders is “we’re completely full.” Some suburban school districts are fast growing and their school buildings may well be full or nearly so. But surely that’s not true in every district (or every building) that has opted out of open enrollment. In any case, all we’re suggesting is that districts participate in open enrollment to the extent they have existing capacity. Participating districts would never be required to build a new school or expand an existing one. If the district has no openings, it simply doesn’t take any students that year.

The other usual objection to open enrollment is that it costs too much, and at first glance there’s something to this. The average amount spent per pupil in Ohio in 2018–19 was $12,472—including state, local, and federal revenues—but a student entering via open enrollment brings just $6,020, all of it state funds. Why would any districts take nonresident students? The answer lies in the difference between fixed and variable costs.

Suppose a third-grade elementary classroom in a non-participating district has eighteen students. This district generally aims for twenty-two pupils per class in grades three through five. Its per-pupil funding for its existing students already pays for the teacher, building administration, support staff, and other fixed costs. If the district opted into open enrollment and accepted four additional students, it would receive an additional $24,000 without likely increasing any fixed costs. As long as the variable cost of another student, such as purchasing textbooks or a Chromebook, is less than $6,000, the district still comes out ahead financially by taking part in open enrollment. Its own residents won’t have their taxes raised to “make up the difference” between the money an open-enrolling student brings with her and the average cost of education in the district.

In sum, any Ohio school district can participate in open enrollment. And the vast majority do. Yet there remains a ring of non-participating districts around the state’s urban centers. It’s not an issue of capacity or cost, as every district decides for itself how many students can enroll and state dollars more than cover the variable costs. Whatever is causing those suburban doors to remain closed, it’s time that the state insist that they open up to open enrollment. They’re public schools, aren’t they?