- Here are some thoroughly debunked—but hard-to-kill—myths about schooling. —Educational Leadership

- Federal education policy needs to give teachers the tools and flexibility to address pandemic learning loss through acceleration and remediation. —Joel Rose

- A poll finds that so-called “anti-racist education” and slow school reopenings could hurt the Democratic party, with repercussions for state and local elections. —National Journal

- “Philly’s Black-led charters schools have alleged bias by the district. Now the claims will be investigated.” —Philadelphia Inquirer

Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2021 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can schools best address students’ mental health needs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging academic instruction?” Click here to learn more.

A miserable student with great academic scores is not an American education story worth celebrating. Besides, it’s a mistake to expect students to thrive academically when they suffer socially or emotionally. All learning takes place in a social-emotional context, and when such context is neglected or abused, it should come as no surprise to see student mental health challenges pop up or get worse. Students’ need time to home in on social-emotional knowledge and skills. We’re better off in terms both of academics and student mental health when we take their social-emotional learning (SEL) seriously.

At this stage of SEL policy maturation, schools and school systems do at least rhetorically take the subject of SEL seriously; teachers and principals understand the value of SEL and believe it’s needed in their halls and classrooms. The trouble is that it’s all too easy to implement SEL poorly: Schools lack high-quality SEL instructional materials, and they lack high-quality professional SEL opportunities. They don’t have meaningful, dedicated time to teach it, much less enable students to learn and practice it. In SEL policy circles, I regularly hear the refrain, “integrate SEL!” as the thing to do, but what narrow focus risks ending up being is a non-evidence-based do-it-yourself sprinkling of SEL added into the cracks and corners of math, history, science, and English language arts classes—the “core four.” Interweaving SEL through the course of the learning day, within the core four and elsewhere, is a worthy endeavor and should be part of comprehensive implementation as a way to reinforce and develop SEL competencies, but it’s secondary to the whole of the SEL project and will not alone deliver on a promise of socially and emotionally competent young people.

To get our SEL house in order, we need to start on the first floor, not as a mile-wide-inch-deep add-on or afterthought, but as a meaningful subject in its own right, something directly teachable, something broadly useful for students’ futures, something warranting teachers’ study, care, and attention, something demanding of HQIM (high-quality instructional materials) and HQPL (high-quality professional learning). Because SEL permeates so much else in youth learning and development—not to mention school climate, curricula, and pedagogy—it should be thought of as foundational, something important for all students, for all teaching and learning. Borrowing an idea that originated with recently retired, award-winning high school teacher, Keeth Matheny, SEL should be considered the fifth core.

SEL as the fifth core would produce better overall mental health outcomes than targeted (tier II), intensive (tier III) or sprinkled SEL would. This claim follows from the prevention paradox: “a large number of people exposed to a small risk may generate many more cases [of an undesirable outcome] than a small number exposed to a high risk.” In other words, it’s better to aim SEL at the whole population of students to prevent undesirable mental health outcomes, rather than aim mental health interventions only at those students who show signs of heightened mental distress or disorder—if we wish to produce better student mental health outcomes.

Dedicated SEL is the preventive tool for the job. It protects against emotional distress for young people, enhances positive attitudes and prosocial behaviors, and enables them to manage mental health challenges. SEL dovetails with trauma-informed practices and is associated with other aspects of mental health that increase students’ attachment to school and motivation to learn, while reducing risky behaviors.

I should hasten to add that some students will still need more targeted and intensive mental health interventions. Universal SEL should not be thought to replace those but to serve in complement to them, commonly under an MTSS (multi-tiered system of support) or a theory of proportionate universalism. (Accepting the prevention paradox, proportionate universalism “suggests that health interventions [including policy] need to be universal, not targeted, but with intensity and scale proportionate to the level of disadvantage and/or social need.”) After all, while SEL works on mental health, it is primarily an educational endeavor, not a healthcare intervention, per se. Importantly, investing in SEL, with educators (ideally) leading the charge, means mental health professionals can be freed up to more successfully attend to tier II and III work. It offers schools and school systems an alternative to more expensive mental health investments that risk falling off a fiscal cliff when federal Covid-19 relief funds run out.

As novel as “SEL as the fifth core is,” it’s not all that new. Many schools across the country already dedicate class time for SEL, have HQIM and HQPL for it, implement it under MTSS, and reinforce SEL competencies throughout the learning day. What is new is that SEL as the fifth core accepts SEL as a subject in its own right and acknowledges SEL’s significance to education.

Jordan Posamentier is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at the Committee for Children. Disclosure: Committee for Children offers research- and evidence- based SEL programs and will offer an SEL for Adults (SELA) program beginning this year.

Meeting the needs of the diverse and growing number of English learners (ELs) is a pressing challenge for many schools, districts, and charter management organizations. Although many general education programs and curricula do not provide all of the specific supports ELs need, pull-out programs for most students generally do more harm than good. Specific English-language instruction is appropriate for students with the lowest levels of proficiency, but emerging and developing learners should primarily participate in mainstream grade-level instruction with targeted supports aimed at building their academic vocabulary and oral and written language. This will be particularly important as schools address ELs’ unfinished learning in the wake of the pandemic. We acknowledge that some consent decrees require pullout programs for EL students, however.

Recommendations

- Ensure EL students can participate in whole-class, rigorous instruction through scaffolds, including by grounding activities in academic vocabulary and using a curriculum that includes specific EL supports.

- Provide intensive small-group instruction and regular opportunities to develop written language skills based on students’ specific learning needs.

- Engage families and build on students’ prior knowledge, including home languages and cultural assets.

- Use federal funding earmarked for ELs to offer extended instructional time over and above the regular school day, such as summer and after-school programs and small-group tutoring.

Rationale

Despite interruptions in in-person schooling, districts and schools must identify and offer targeted supports and accommodations to EL students. A new “EdResearch for Recovery” guide notes that federal waivers issued in spring 2020 are unlikely to recur and recommends using new digital tools to better serve ELs. These include direct outreach to families, such as through translated text messages, as well as new online professional learning for teachers and paraprofessionals.

Perhaps the most widely respected guidance on EL instruction has emerged from a project out of Stanford University called Understanding Language. Co-chaired by scholars Kenji Hakuta and María Santos, Understanding Language has considerably advanced educator knowledge about the importance of rigorous, grade-level instruction for ELs. The initiative has articulated six principles for effective lesson planning and delivery:

- Provide ELs with opportunities to engage in discipline-specific practices that build conceptual understanding and language competence in tandem.

- Leverage students’ home languages, cultural assets, and prior knowledge.

- Ensure standards-aligned instruction for ELs is rigorous, grade-level appropriate, and provides deliberate and appropriate scaffolds.

- Account for students’ English proficiency levels and prior schooling experiences.

- Foster autonomy by equipping EL students with the strategies necessary to comprehend and use language in a variety of academic settings.

- Employ diagnostic tools and formative assessments to measure students’ content knowledge and academic language competence.

In its Practice Guide on the subject, the Institute for Education Sciences considers evidence from nineteen separate high-quality studies. The guide supports small-group interventions for EL students, but also stresses “enhancing the core instructional program” in three of its four recommendations. These are:

- Teach a set of academic vocabulary words intensively across several days using a variety of instructional activities.

- Integrate oral and written English language instruction into content-area teaching.

- Provide regular, structured opportunities to develop written language skills.

- Provide small-group instructional intervention to students struggling with literacy and English language development.

The guide also notes that teachers should find ways to group English learners with their non-English-learner peers because students in heterogeneous groups are likely to benefit from hearing opinions or oral language expressions from students at different proficiency levels. Other discussions of “what works” underscore the importance of explicit and intense instruction in academic vocabulary and the related need for “engaging students in academic discussions about content.” Thankfully, several high-quality English language arts curricula on the market are designed to support teachers in delivering instruction that meets the needs of EL students.

Quality language and literacy instruction occurs throughout the school day and across content areas. All teachers in the building, including history, math, science, and other disciplines, should incorporate these recommendations.

Reading list

Baker, S., Lesaux, N., Jayanthi, M., Dimino, J., Proctor, C. P., Morris, J., Gersten, R., Haymond, K., Kieffer, M. J., Linan-Thompson, S., and Newman-Gonchar, R. (2014). “Teaching academic content and literacy to English learners in elementary and middle school (NCEE 2014-4012).” Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Bunch, G., Kibler, A., and Pimentel, S. (2012). “Realizing Opportunities for ELLs in the Common Core English Language Arts and Disciplinary Literacy Standards.” Presented at the annual meeting of the Understanding Language Conference, January 2012.

Goldenberg, C. (2013). “Unlocking the Research on English Learners,” American Educator. Summer 2013. 4-11.

Goldenberg, C. (2008) “Teaching English Language Learners,” American Educator. Summer 2008. 8-23, 42-44.

Mavrogordato, M., Callahan, R., DeMatthews, D., and Izquierdo, E. (2021). “Supports for Students Who Are English Learners.” EdResearch for Recovery.

Santos, M., Darling-Hammond, L., and Cheuk, T. (2012). “Teacher Development to Support English Language Learners in the Context of Common Core State Standards.” Presented at the Understanding Language Conference, January 2012.

“Understanding Language,” Stanford Graduate School of Education (Retrieved May 12, 2021).

NOTE: On May 11, the Ohio Senate’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on Senate Bill 145, a proposal to revise school and district report cards in the state. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy provided proponent testimony on the bill. These are his written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

I’d like to start by commending the bill sponsor and the committee for tackling this important and incredibly complex issue. School and district report cards perform a variety of critical functions. For parents, the report cards offer objective information as they search for schools that can help their children grow academically and reach their potential. For citizens, they remain an important check on whether their schools are thriving and contributing to the well-being of their community. For governing authorities, such as school boards and charter sponsors, the report card shines a light on the strengths and weaknesses of the schools they are responsible for overseeing. And, finally, as we are reminded during challenging times like this, it can help public officials identify schools in need of extra help and resources.

Because of the many roles it plays, it’s essential that Ohio get it right when designing a report card. The current report card has some important strengths and has even drawn national praise from the Data Quality Campaign and the Education Commission of the States. Nevertheless, there are facets of the report card that can and should be improved. Fordham published a report in 2017, Back to the Basics, calling for a variety of reforms to Ohio’s report card framework including simplifying it and making it fairer to schools serving high percentages of economically disadvantaged students.

As you consider how to improve the report card, we urge you to keep four principle-based questions at the forefront.

- Does the report card support equity and ensure high expectations for all students and that each student counts?

- Does the report card advance transparency and offer parents and communities clear, simple, honest information about school performance?

- Is the report card fair and does it give every school the opportunity to demonstrate growth and improvement?

- Is the report card accurate and ensure components are measuring what is intended?

SB 145 significantly reworks the state report card framework. What follows is a summary of the most important changes with a short analysis of how they adhere to the principles that I’ve described.

- Switching to a star rating system: While Fordham remains a fan of the simplicity and transparency inherent in using A to F grades, we recognize that a state system that views a “C” as average performance creates a disconnect for families that often view a “C” on a student’s report card as a time to intervene. For that reason alone, a shift makes sense. The adoption of a 5-star framework is an excellent alternative. It benefits from being widely used to rate preschools, hospitals, and even products and services on Amazon and Yelp. This is a huge advantage when compared to text-based descriptors that can be either misleading or hard to understand in districts like Columbus where families speak dozens of languages. A 5-star rating system is simple and maintains transparency.

- Maintaining, but modifying, the overall rating: Akin to a GPA, an overall rating offers a broad sense of performance by combining results from disparate report card measures. It focuses public attention on the general academic quality of a school contributing to both transparency and fairness. In contrast, a system without a final rating risks misinterpretation. It enables users to “cherry pick” high or low component ratings that, when considered in isolation, could misrepresent the broader performance of a school. SB 145 goes a step farther to increase the usefulness of overall grades by ensuring that student growth—a measure fairest to high poverty schools—will never be less than 25 percent of a school or district’s overall grade. It also introduces half-stars to provide for greater differentiation in the overall ratings.

- Reducing the number of graded components: Simplicity when presenting ratings is critical for a report card to be useful. Report cards for school districts currently have 15 different grades. When you grade too many things, you diminish the value and usefulness of every measure. SB 145 slashes the number of graded measures to six components and one overall grade.

- Adding context to every graded measure: While already using a well understood 5-star rating system, SB 145 goes a step further to add even more context to the ratings. It calls for the inclusion of text descriptions to supplement rather than supplant the star system, colors to add clarity so that a 3-star rating will be shaded green helping to ensure communities understand it represents acceptable performance and doesn’t come with a negative connotation, and trend arrows to show within a component if a school’s performance is improving or declining. These changes will make the report card fairer and more accurate by increasing the context around the ratings.

The changes just described focused on the overall report card framework. Next, I’ll dive into some of the changes surrounding the individual report card components. These are critical improvements, because poorly structured components feed into the overall rating and harm public confidence in the report card.

- Streamlining the achievement measure: SB 145 eliminates the indicators met component and bases the rating solely on performance index. This simplifies the measure and contributes to equity because the performance index doesn’t just give a school credit when a student “passes” a state assessment but also when students achieve above and beyond the proficiency mark. It properly keeps the focus on every student reaching his or her potential. Some have advocated for a sixth category under performance index. We oppose doing that. It would ruin long-term comparability and could require increasing the length of state assessments.

- Changing value-added (student growth): SB 145 makes a couple of changes to the value-added component that should increase fairness. First, it shifts to a 3-year weighted average when calculating growth which ensures that one bad year won’t sink a school’s rating. It also eliminates the current demotion when one individual student group doesn’t perform well. Importantly, the performance of student groups will still impact a school’s rating but will be a part of the equity measure.

- Adds additional data around graduation ratings: The bill doesn’t make major changes to the graduation rate component as its structure is generally locked-in by federal requirements. It does provide additional context by disclosing how many students with disabilities are continuing their K-12 education—consistent with law that allows them to remain a student until age 22.

- Shifting from gap closing to equity: SB 145 reworks the component known as gap closing and renames it equity. The current gap closing component allows schools to earn credit when a student group hits either performance index or value-added goals. This creates a very real risk that the academic performance of a student group could be hidden and the group won’t get the supports and resources it deserves to make strong academic progress. The equity component under SB 145 requires that both achievement and growth for each student group, not one or the other, are factored into the rating. This will enhance the overall focus on equity in the system.

- Restructuring the Early Literacy measure: At-Risk K-3 Readers, the current early literacy component, is one of the most criticized elements of the report card. It focuses solely on the percent of a school’s struggling readers that it helps to catch up. This opens the door for situations where 90 percent of a school’s students read on grade level, but the school receives a low rating for helping its struggling readers. SB 145 tackles this issue by basing half of a school’s rating on the critical task of helping struggling readers to make progress. The other half though is based on the percent of third graders who demonstrate reading proficiency. By considering both improvement and overall performance, the new early literacy measure is fairer to all schools and supports equity by maintaining an emphasis on the importance of all students learning to read. This committee has heard calls for this measure to be based on the promotion rate associated with the third-grade reading guarantee. That would be a huge step backward. Ohio currently has a third-grade promotion rate of 95 percent but a proficiency rate on the third-grade reading assessment of only 67 percent. Success must continue to focus on third-graders reading on grade level. The measure in SB 145 does just that.

- Overhauling prepared for success: Early literacy may be criticized, but many in the education community despise the prepared for success component. Their concerns are not unfounded: The measure was constructed too narrowly and had an overly ambitious—perhaps even unrealistic—grading scale attached to it. That being said, it’s probably the most important measure on the state report card. It looks beyond state test scores—something we’d all like to do—to determine how ready young adults are when they leave high school. For transparency and accuracy purposes, this component should be reformed. But it shouldn’t be abandoned. SB 145 does just that. It eliminates the current two-tier bonus structure, greatly expands the ways students can demonstrate readiness for college and career, and gives credit to schools and districts for year-to-year improvement. The new measure will be fairer to schools, especially those with low baseline readiness rates, while also supporting equity by maintaining high expectations for all students.

Through its adherence to the principles of equity, transparency, fairness, and accuracy, SB 145 would create a state report card that reinforces a key tenet of education policy. Namely, that all students—given the proper support—can learn and achieve at high levels. We urge this committee to support this important piece of legislation.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony. I’m happy to answer any questions that you may have.

Trouble continues at the National Assessment Governing Board (NAGB), the policy body for the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Last week, I wrote about the draft “gag order” that board chair (and former Mississippi governor and RNC chair) Haley Barbour had issued to members, which would radically cramp their ability to communicate with each other and with outside advisors, critics, friends, and random folks. Subsequently, the board’s executive committee and staff have reportedly set about to find a less burdensome way of allowing members to engage in reasonable communications without running afoul of government-wide open-meeting requirements. We’ll hope that goes well.

Meanwhile, however, a legitimately controversial new framework for future reading assessments is back on the board’s agenda at its quarterly meeting this week, and it’s not looking good, either for comity within the board or for the future of the country’s foremost assessment of students’ reading prowess.

NAEP’s reading assessments in recent years rely on a 2009 framework that replaced one in use since 1992, but results have been able to be reported on an unbroken trend line dating all the way to 1992 (save for a “dotted line” prior to 1999 when testing accommodations began for children with disabilities). It’s a very important continuous gauge and one that shouldn’t lightly be replaced.

Assessment frameworks do get revised, updated, and sometimes replaced from time to time, however, and in late 2017, NAGB’s Assessment Development Committee (ADC) began a review of the reading framework, including a quest for expert input, research, and advice. A year later, the board awarded a contract to WestEd to “conduct an update of the NAEP Mathematics and Reading Assessment Frameworks,” as well as specifications for the tests themselves. That led to the assembling by 2019 of an elaborate set of consultants, committees, and staff: a thirty-two-member “visioning panel,” a seventeen-person “development panel,” an eight-member “technical advisory committee,” and ten WestEd employees.

They were ambitious, to put it mildly, and some of their ambitions were destined for controversy. The “visioning” group, in particular, wanted future NAEP reading assessments to incorporate reading in various media, not just words on paper; to emphasize the “deep reading” and “disciplinary reading” that are stressed in some new state academic standards (and the Common Core) and a variety of new reading tests used elsewhere; to recognize that “texts inevitably are cultural and political in nature”; to take account of differences among test-takers, not only in cultural and racial contexts, but also in levels of motivation and interest; and to compensate for differences in students’ background knowledge and vocabulary.

The goal was to develop a new reading framework that the board would adopt in time for the 2025 assessment cycle, which has since shifted to 2026 due to an overall Covid-induced delay in much of the NAEP calendar. But when a draft was put out for public comment in mid-2020, it soon became clear that reaching agreement would not be easy.

Thousands of comments flooded in. Many welcomed the developers’ very different “vision” of reading and its assessment. But there was also pushback on a host of issues, including two that proved especially volatile. The drafters had set out to reframe reading and its assessment in “socio-cultural” terms, seemingly in opposition to the “cognitive” terms that have long undergirded the assessment process—and not just in reading. And in the name of “equity,” the drafters proposed a variety of changes in test design, administration, scoring, and analysis, as well as provision of various “scaffolds” for test-takers, such as supplying background knowledge to help them understand the content or meaning of terms and texts that they encounter in the course of the assessment. The lead advisors on this new framework (notably David Pearson and Gina Cervetti) have done their utmost throughout to minimize or compensate for the role of background knowledge in NAEP’s assessment of students’ reading comprehension, even though—as thoroughly documented by the likes of cognitive psychologist Dan Willingham, E.D. Hirsch, and many others—such knowledge is omnipresent (or not) and fundamental, which becomes immediately obvious when one exits the classroom and enters the real world of reading. They and a host of other framework advisors and staff members have also striven throughout the process to view reading through a “socio-cultural” lens rather than as a universal skill.

This led observers such as Johns Hopkins professor (and former New York State education commissioner) David Steiner and Emory English professor Mark Bauerlein to warn that making such changes in NAEP’s approach to reading would actually mask crucial information that educators need to help children read better. “Rather than allowing poor performance to serve as a signal that large knowledge gaps should be fixed through better education,” they wrote in City Journal, “we will simply lower the impact of background knowledge on the reported test performance.... If NAEP follows this route,” they concluded, “its assessment will no longer be a reading test that we can trust to demonstrate where students need more help—and where teachers should focus their efforts.”

Much debate followed within the board, following which changes were made in this very lengthy and dense document. The current version, which goes before NAGB this week (though final decisions have been put off until August), runs more than 150 pages. The ADC and its advisors have indeed made a number of revisions, but most appear to be cosmetic and rhetorical, intended to mollify critics more than to alter the fundamental changes that the new framework would make in reading assessment.

The impact of those changes goes far beyond NAEP, of course, as the framers of this framework understand and presumably intend, for a recasting of NAEP’s view of reading proficiency and its way of testing that proficiency will gradually percolate through the entirety of K–12 education in America, seeping into state academic standards and assessments, into textbooks, teacher preparation, and much more.

A number of NAGB members expressed serious reservations about the ADC’s recasting of reading, at least as troubled by how it is justified and presented than in the actual changes it will produce in the test materials that kids will face, although it’s not yet clear whether those changes will result in NAEP having to start a new trendline when it reports future reading scores. The heat generated by these intra-board disagreements is a problem in its own right, as one of NAGB’s foremost assets over the past several decades has been its capacity to reach consensus on important matters. Will this important twenty-six-member governing body henceforth come to resemble the factionalized, politicized, schismatic (and gridlocked) ways of so many other key policy bodies, most visibly the U.S. Congress? Yet nothing is more fundamental to what NAEP does and what NAGB presides over than assessing the most basic of all academic skills, the first of the three R’s.

Seeking to find a way out of this grave situation, Board member Russ Whitehurst, himself the founding director of the Institute of Education Sciences and a formidable authority on education research, volunteered to edit the framework document. His goal was to shorten it, make it accessible to ordinary readers and purge it of the faux research, controversial rationales, and inflammatory rhetoric that had made it so contentious.

The ADC chair threw a fit, insisting that Whitehurst shouldn’t do this, but Chairman Barbour encouraged him to proceed. And about ten days ago, Whitehurst submitted his slimmed down, cooled down, and simplified revision, noting as he did that his edits “do not require any changes in the plans for the 2026 reading assessment.” It was, in my view, a huge improvement that might actually lead to something the entire board—and, more importantly, an on-edge, overheated country—might comfortably live with.

But what followed was pretty awful. On Friday evening, through the dubious magic of Zoom, I watched ADC members (all of them, as far as I could tell) savage the Whitehurst redraft—and Whitehurst himself—for having dared to mess with their handiwork. Worse, they may have been egged on by a NAGB staff member who, when circulating the Whitehurst edits to board members, accompanied them with her own lengthy memorandum purporting to show how all of his edits did violence to the committee’s own redraft. This was the most glaring example of staff manipulation of members of a governing body that I’ve seen in a long while, seeming to exploit the fact that the ADC is itself comprised almost entirely of well-meaning teachers and other building-level practitioners and laymen, rather than experts on the sometimes-obscure issues and research that’s involved.

The session resembled a Maoist “denunciation” of someone for not wholeheartedly supporting the cultural revolution. Fortunately, the chosen victim, Russ Whitehurst, had wisely opted not to be insulted and reviled in person. In that sense, it was actually more like a modern-day faculty meeting or editorial board meeting where an absent individual gets “canceled” for deviating from the progressive party line.

Whitehurst was excoriated up one side and down the other for his effrontery, for being out of step with feedback the committee had received from “the field,” but above all for changing the framing and rationale for the new framework itself.

Before the ADC members piled on, several members of the technical panel that had advised them on the new framework rushed through a confusing presentation of an ambiguously-worked survey of state testing directors. The techies sought to present those survey results as evidence that states try to exclude “knowledge” from their reading tests. That’s not what I was seeing as the slides flashed past on the screen, nor did anyone pause on the sticky question of whether vocabulary itself is a proxy for knowledge that state tests do not in fact exclude.

The “get Russ” attack that followed was led by committee member Christine Cunningham, whose day job is Professor of Practice in Education and Engineering at Penn State and who is, to my knowledge, the only academic on the ADC. She is formidably articulate and was loaded for bear, but her own training is in biology and science education, not cognitive science or reading. Almost all the evidence she cited regarding education research came from a single source.

Dr. Cunningham swiftly took the (virtual) floor and was prepared with a lengthy bill of particulars as to what she found wrong both with Whitehurst’s rewrite and with his motivation in doing it at all. She periodically interrupted herself to ask fellow committee members to raise their hands to signal agreement with her on various points. Another observer analogized this to a series of “loyalty oaths” among committee members. And yes, the other members did pile on, all decent, well-intentioned people, but not visibly conversant themselves with the research base for reading comprehension.

Students’ background knowledge was one big issue. Dr. Cunningham clearly belongs to the faction that thinks it should have no place in the assessment of reading comprehension. The other big issue was whether to ground the new reading framework in a “cognitive” understanding of reading or a “socio-cultural” view. Dr. Cunningham insisted on the latter and declared (citing her sourcebook) that the “latest” research requires it.

It was, frankly, a horror show—but nobody on the NAGB staff said a word, not even to remind committee members that Chairman Barbour had invited the rewrite. Unless cooler heads somehow prevail, we can expect further fireworks and denunciations at this week’s meeting of the full board. Which leaves me wondering whether there’s any way to unscramble these eggs at this point—and what this portends both for the future of reading assessment and for the future of the National Assessment Governing Board.

Editor’s note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute recently launched “The Acceleration Imperative,” a crowd-sourced, evidence-based resource designed to aid instructional leaders’ efforts to address the enormous challenges faced by their students, families, teachers, and staff over the past year. It comprises four chapters split into nineteen individual topics. We're publishing each as a stand-alone blog post.

Targeted interventions for elementary students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) should not occur at the expense of their also receiving quality whole-group instruction with the remainder of the class. As much as possible, every opportunity should be provided to offer student supports that scaffold grade-level instruction, particularly in English language arts, where the development of academic vocabulary and the opportunity to advance oral language competency are vital to literacy success.

Recommendations

- Keep struggling students together with their general-education classmates as much as possible, even as their specific learning challenges are also being addressed in small-group Tier 2 settings. The actual instruction students receive in lower-performing groups can be inferior to that received by students in higher-performing groups, much like how assigning students leveled reading books can keep them permanently behind their peers.

- Structure small-group Tier 2 interventions to maximize their positive impact. The literature is clear about the value of small-group intervention for twenty to thirty minutes per day to help students with learning difficulties or unfinished learning.

- Focus Tier 2 time on high-impact skills and topics. In reading, small-group interventions should focus on foundational skills and fluency or comprehension issues related to specific content in the curriculum. The science is long on the benefits to students with reading disabilities of extra time spent on explicit, repetitive, structured instruction that can help them make the connections between the sounds of spoken words and the letters that represent those sounds. Though more of the literature on multi-tiered instruction has occurred in reading, the principles are equally appropriate for students struggling with mathematics.

- Select and use high-quality instructional materials that include robust discussions, guidance, and tools to scaffold lessons to meet the needs of all learners. Tier 2 interventions should be provided using the core curriculum and be additive, augmenting rather than replacing students’ participation in grade-level lessons as part of the class. Again, much of the benefits of such curricula are experienced in a whole-class setting.

Rationale

In its Practice Guides on Response to Intervention strategies in reading and math, the Institute of Education Sciences cites numerous studies recommending “intensive, systematic instruction in small groups to students who score below the benchmark on universal screening.”

In reading, it is recommended that instruction address foundational reading skills identified through screening tools, and that small groups meet between three and five times a week for twenty to forty minutes each time.

In mathematics, the evidence indicates that instruction in these small groups should be explicit and systematic. Lessons should focus on common underlying structures in solving word problems, use visual representations, and build fluent retrieval of basic arithmetic facts.

Reading List

Alsalamah, Areej. (2017). The Effectiveness of Providing Reading Instruction Via Tier 2 of Response to Intervention. International Journal of Research in Humanities & Social Sciences. 5(3), 6-17.

- Studies of Tier 2 instruction have not been done on schools where Tier 1 instruction is necessarily strong.

Anderson, Richard C., Hiebert, E., Scott, J., Wilkinson, I., Becker, W., and Becker, W. (1988). BECOMING A NATION OF READERS: THE REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON READING. Education and Treatment of Children, 11(4), 389–396.

- Cited here as the source of concerns about the differences in how lower-level and higher-level students are engaged by teachers.

Gersten, R., Beckmann, S., Clarke, B., Foegen, A., Marsh, L., Star, J. R., & Witzel, B. (2009). Assisting students struggling with mathematics: Response to Intervention (RtI) for elementary and middle schools (NCEE 2009-4060). Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C.M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., and Tilly, W.D. (2008). “Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to Intervention and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. A practice guide. (NCEE 2009-4045).” Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Hoff, Naphtali. (2002). “An Analysis of Appropriate Groupings and Recommended Strategies and Techniques for Reading in the Classroom.” Independent Study Research Paper, Loyola University.

- Teachers tend to ask more stimulating questions when working with higher-level students.

Johnson, E. S., and Boyd, L. (2013). Designing Effective Tier 2 Reading Instruction in Early Elementary Grades with Limited Resources. Intervention in School and Clinic, 48(4), 203-209.

- Interventions should include knowledge-building activities.

Shaywitz, S. and Shawywitz, J. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. Alfred A. Knopf.

Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2021 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can schools best address students’ mental health needs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging academic instruction?” Click here to learn more.

As vaccine distribution picks up pace across the country and governors join President Joe Biden’s push for schools to return to in-person instruction by May, leaders are moving quickly to ensure that reopenings happen safely. The School Superintendents Association, AASA, estimates that the average district will spend more than $1.7 million on safety protocols, such as facility improvements and personal protective equipment—much of it allowable expenses under the new $1.9 trillion stimulus package.

But physical health precautions shouldn’t be the only considerations for defining a “safe” school reopening. While young people, on the whole, have fared better physically than adults during the pandemic, researchers say isolation—such as that caused by school closures and quarantining—is leading to a “mental health tsunami.” In a recent survey, two-thirds of parents said their child had experienced mental or emotional challenges, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts, in the last month.

Unfortunately, this was a problem long before COVID-19. About 20 percent of students need mental health services, with the onset of half of cases occurring by age fourteen, and only a small portion will access appropriate care. Early intervention, however, can mitigate long-term consequences of mental illness. Yet the infrastructure for students to receive mental health services at school is woefully underdeveloped. Only one in five students obtains needed mental health services through school.

Nearly half of public school students are enrolled in a school without a psychologist on staff, and less than 3 percent of schools nationwide meet the recommended social worker-to-student ratio.

Classroom teachers and staff are often the first adults outside the family to interact with students experiencing psychological distress. Thankfully, the recent stimulus packages allow schools to allocate funds toward mental health-related services, which could include professional development to train teachers and staff members to recognize signs that students are struggling. With the appropriate training, teachers and other school staff can learn to manage conversations with students to help them navigate challenges and, if necessary, connect them with mental health support services.

Here are four ways schools can prioritize mental health as part of a safe reopening plan:

1. Prepare teachers and staff to recognize signs of distress among students.

Identifying signs of psychological distress in students can’t rest entirely on school counselors and psychologists. Every adult member of a school community should be the eyes and ears for students who are struggling. Professional development programs can empower school employees to recognize emotional and behavioral cues that might point to more serious mental health concerns. That identification, as well as the skills to approach, talk to, and if necessary, refer students in psychological distress, is integral to supporting school mental health initiatives. As teachers and staff members become more adept at recognizing the signs, the safety net expands, providing a safer and more trusting environment, so learning can move forward. Employees equipped with these skills provide a strong, sustainable foundation for promoting wellness and school safety.

2. Increase availability of mental health services and resources.

When asked about providing mental health services to students, 75 percent of surveyed public school principals cited inadequate funding as a barrier, as well as access to mental health professionals and community support. Allowing local education agencies to use stimulus funding for these services is a good start. But district leaders must prioritize school-based mental health services. Access to mental health resources should be as important a component of school safety as pandemic-related protocols like social distancing, wearing masks, and disinfecting classrooms.

3. Address stigma through mental health literacy.

A simple approach for schools looking to promote mental health is to encourage conversations that normalize the topic and propagate positive attitudes. Minimizing the shame and guilt students experience as a result of mental health concerns is a critical component in eliminating stigmas that prevent students from seeking help. When administrators, teachers, and staff have the resources and skills to support students who are struggling, the culture shifts. Fostering positive student-teacher relationships also helps prevent teacher stress and burnout, increasing job satisfaction. A nurturing school climate provides a safe place for students to seek mental health support services, which ultimately will strengthen learning and academic success.

4. Teach students to manage feelings through social-emotional learning.

Social-emotional learning helps students regulate their emotions and behaviors. An analysis of programs that focus on emotions, relationships, and decision-making revealed better academic performance and fewer problems with conduct, emotional distress and substance use, all of which contribute to school safety. Through social-emotional instruction, students learn to identify their feelings, form positive relationships, set achievable goals, and demonstrate empathy toward peers and adults. School districts can train teachers to incorporate lessons on social-emotional skills into their curricula, then give students an opportunity to put those skills into practice.

—

Historically, there has been a need for schools to prioritize mental wellness—not only for students, but for teachers, as well. The pandemic has shined a spotlight on the need for a broader definition of school safety, one that considers the social and emotional needs of the school community. Let’s seize upon this era of increased awareness to focus on emotional well-being and ensuring that schools can provide students with a safe, supportive environment where learning can thrive. For that to happen, school leaders and policymakers must be ready to prioritize prevention through a mental health lens.

Editor’s note: This first appears in the 74 Million.

There’s not a lot that right and left agree about right now, but one big thing is the sorry state of civil debate. Whether the fault lies with social media, institutional erosion, or something else, the result is the same: a nation of people who aren’t good at listening to ideas they don’t already hold, assessing them thoughtfully, and discussing them in respectful terms.

That helps explain the surge of interest in revitalizing civics education—although that interest too takes different shapes and is expressed in different terms on left and right and around the country.

Indeed, it may be useful to set aside the obvious left-right divides for a moment in order to focus on how different are the views to be found across this broad, diverse land.

While it may seem far afield, consider that hotly debated touchstone of Americana: barbecue. With barbecue, there’s a broadly shared notion of the goal—to cook an enjoyable meal, usually involving protein—but lots of different views on just what “enjoyable” entails and how to get there. With barbecue, the differences pertain to decisions about sauce, cooking style, cut of meat, and more. With civics, the differences pertain to what students are expected to know, how it’s taught, what students are asked to do, and so forth.

For the longest time, civics instruction emphasized knowledge: how Congress creates laws, what the Supreme Court does, how federalism works, what’s in the Bill of Rights, and so forth. That focus was healthy, as far as it went, if poorly executed. Today, essential knowledge about civics (and U.S. history) are elegantly distilled into the hundred questions asked of immigrants seeking to be naturalized as U.S. citizens. (Last year, the Trump administration substituted a more challenging 128-question version. Recently, the Biden administration reverted to the 100-question version first used in 2008.) We love those questions, both versions of them, and believe that students who can answer them before graduating high school are far better prepared for citizenship. Kudos to the Joe Foss Institute (now part of Arizona State University) for encouraging states to make passing that test a requirement.

Yes, we’re knowledge junkies. But we also understand that cramming kids with information is just the beginning. Especially when it comes to civics, it’s crucial that students also understand what they know and why they’re learning it.

Students need to be able to wrestle with big questions and formulate their own answers. In civics, in particular, they also need to learn how to function as citizens and why it’s important that they learn to do so.

The “roadmap” for teaching civics and U.S. history recently released by the “Educating for American Democracy Project” does a nice job of posing those questions in ways that teachers can turn into curricula and lessons across the primary and secondary grades. The authors term it “an inquiry-based” approach that’s “organized by major themes and questions, supported by key concepts.” The upshot is an emphasis on questions rather than answers, making the roadmap more malleable to state and local (and school- and teacher-level) priorities. We think this is a healthy thing, much as a nationwide roadmap for barbecue would be better off guiding would-be chefs through the many regional preferences rather than insisting that (say) “barbecue sauce requires mustard.”

The roadmap points, we think, to sound core principles for civics (and history) education. It features unapologetic discussions of patriotism, Constitutional democracy, and virtue, and American students certainly need more of those.

At the same time, one of its principles calls for “inspir[ing] students to want to become involved in their constitutional democracy and help to sustain our republic.” While we like the sentiment, the phrasing here leans into the contentious realm known as “action civics.” Things get heated in that area because, while there are plenty of sensible ways to engage kids in practical civics, there are also too many examples of the push toward “action” conscripting students into progressive issue advocacy. By contrast, it’s hard to find examples of students being allowed—much less encouraged—by their schools and teachers to mobilize for right-leaning causes.

Things get even more contentious because some of today’s ardent civics reformers seek to involve Uncle Sam in backing their efforts, especially via the billion-dollar Educating for Democracy Act. Much of the funding it authorizes would flow by formula to states, with the rest going directly to some of the many organizations active in the civics field. And anyone familiar with this space would note that more than a few of the organizations eager to pocket federal dollars seem intent on using taxpayer resources to turn more kids into like-minded activists and agitators.

Of the Educating for Democracy Act, Emory professor Mark Bauerlein has written, “It’s standard left-wing practice to speak in traditional liberal terms while letting radical content filter into a project at the implementation stage, after public attention has waned.” National Review’s Stanley Kurtz has repeatedly raised similar cautions. And the National Association of Scholars has formed a “coalition to stop action civics.”

These critics are not wrong to flash a warning light, particularly if Uncle Sam gets involved. We’ve lived through too many painful examples where the federal embrace turns a legitimate state-and-local (or private) initiative into a political football.

Ultimately, all civics instruction needs to teach essential knowledge about civic responsibilities, constitutional rights, and how republican government works. Beyond that, as with barbecue, there are going to be dozens of recipes. While we worry about the versions of action civics that may hold sway in some deep blue outposts, our real concern is the prospect of woke bullies using federal funds and clout to push their agendas on unwary and unwilling communities across the land.

The “roadmap” offers a potentially constructive path forward, one that will necessarily be interpreted and implemented in different ways around the country. Some of those ways we will assuredly applaud, others we’ll deplore. That’s the American system in action. Hell, it’s not a bad lesson in civics, all by itself.

Editor’s note: This was first published by The Hill.

NOTE: Today, the Ohio Senate’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard invited testimony on HB 110, the state budget bill. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy was invited to testify on topics related to school funding and interdistrict open enrollment. These are his written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a charter school sponsor.

Last week, I touched on a host of school funding and education policy issues in House Bill 110. In that testimony, I mentioned some of the strengths of the House school funding plan, including its elimination of funding caps, the increased focus on providing adequate resources for low-income students, and the shift to direct fund choice programs. The House should be commended for their work in those areas. In today’s testimony, however, I’ll limit my comments to three specific areas in school funding that merit further discussion: guarantees, interdistrict open enrollment, and outyear funding.

Guarantees

Ohio has long debated “guarantees,” subsidies that provide districts with excess dollars outside of the state’s funding formula. These funds are typically used to shield districts from losses when the formula calculations prescribe lower amounts due to declining enrollments or increasing wealth. In FY 2019—the last year in which funds were allotted via formula—335 of Ohio’s 609 school districts received a total of $257 million in guarantee funding. The guarantee, it’s worth noting, isn’t directly tied to poverty: A number of higher-wealth districts benefitted from the guarantee in 2019.

Guarantees undermine the state’s funding formula whose aim is to allocate dollars efficiently to districts that most need the aid. Districts on the guarantee receive funds above and beyond the formula prescription, while others receive the formula amount—sometimes even less due to the cap. Because guarantees are usually related to enrollment declines, they effectively fund a certain number of “phantom students” who no longer attend a district.

Among the main ideas of HB 110 is to get all districts on the same formula. That’s exactly the right goal. But while the legislation removes caps, it does not adequately address guarantees. Let me raise three specific issues:

- Permanent guarantee. In a new section of law (3317.019), House Bill 110 creates a permanent guarantee that ensures no district loses state funding on a per-pupil basis starting in FY 2024. While no estimates have been released on how many districts this may apply to, or what the cost to the state may be, it’s concerning to see the continued reliance on guarantees to fund some districts.

- Supplemental targeted assistance. In another new section of law (3317.0218), House Bill 110 would send excess money outside of the formula to districts where significant numbers of resident students have enrolled in choice programs. Certain low-wealth districts where more than 12 percent of students attended public charter schools or used private-school vouchers in 2019 would receive an annual bump in state funding, anywhere from $75 to $750 per pupil. This policy, which is akin to funding phantom students, is estimated to cost the state $56 million per year. That may not sound like a large amount of money, but it’s happening at the same time the budget is being phased in and districts are receiving less—sometimes much less—than the formula says that they should.

- Staffing minimums. Though not a guarantee in a traditional sense, HB 110 includes something like it in its base cost model. School districts—though not charter schools—are guaranteed a minimum number of special teachers, and SEL and administrative staff, even when the plan’s specified staff-to-enrollment ratios would have resulted in lower staffing support. Such minimums boost the base costs of low-enrollment districts, thus creating a small-district subsidy that is funded like a de facto guarantee within the base cost formula.

Interdistrict open enrollment

Open enrollment is an increasingly popular public school choice program, especially among families living in Ohio’s rural areas and small towns. More than 80,000 students today use interdistrict open enrollment to attend public schools in neighboring districts. Research commissioned by Fordham has shown that students who consistently open enroll benefit academically, especially students of color.

Under current policy, the funding of open enrollees is fairly straightforward. The state subtracts the “base amount”—currently a fixed sum of $6,020 per pupil—from an open enrollee’s home district and then adds that amount to the district she actually attends. Apart from some extra state funds for open enrollees with IEPs or in career-technical education, no other state or local funds move when students transfer districts.

In a wider effort to “direct fund” students based on the districts they actually attend, House Bill 110 eliminates this funding transfer system for open enrollment. Open enrollees are included in the “enrolled ADM” of the district they attend and thus receive the same level of state funding as resident pupils of that district. While this seems to make sense at face value, the approach results in significantly lower funding for most open enrollees relative to current policy, creating disincentives especially for mid- to high-wealth districts to accept open enrollees.

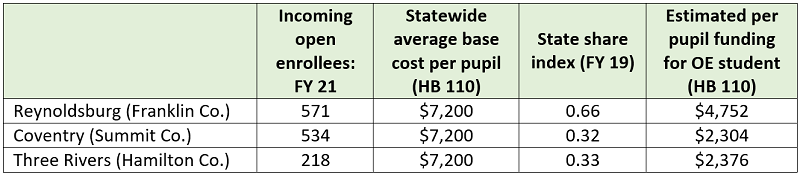

The table below illustrates how applying the state share reduces funding for open enrollment, using three districts that have significant numbers of open enrollees this year. Note, we use the district’s state share index from FY 2019 and the average statewide base cost under HB 110, because those data were not available in the funding simulations. What we see is that open enrollment funding is significantly reduced relative to the current $6,020 per pupil once the state share is applied. Will districts like Coventry and Three Rivers continue to offer open enrollment when per-pupil funding is cut by more than half? Will wealthy districts that currently refuse to participate open their doors when the state funding is so low? Remember that under current policy districts voluntarily participate in the program—it’s not required—so the funding amounts are crucial to opening these opportunities to students.

Illustration of open enrollment funding in HB 110

Some have suggested that the new formula when fully phased in won’t create a disincentive in regards to open enrollment and will adjust to produce a funding amount similar to what open enrollees currently receive. If true, that’s fantastic. It’s not in the legislative analysis, and it’s not explicitly in HB 110. This is too important to leave to chance. Please add language to ensure that open enrollees continue to receive adequate funding.

Outyear funding

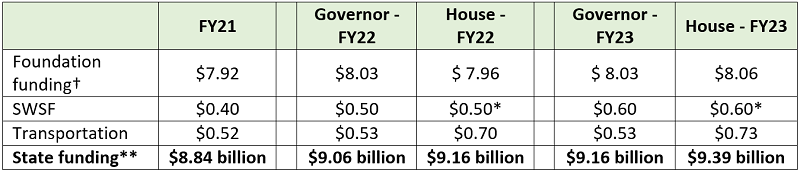

As has been widely reported, the overall price tag of the House funding overhaul is estimated to be an additional $2 billion per year. Yet, as the table below indicates, HB 110 calls for generally modest increases in education spending in the next biennium. Relative to the Governor’s plan, the House raises state education funding by roughly $100 million in FY 2022 and $230 million in FY 2023. Most of those dollars go into transportation rather than into the classroom.

An overview of state education funding, current and proposed (in billions)

*In the House plan, the Student Wellness and Success Funds remain a standalone line item, but are used to fund an increase in the economically-disadvantaged component of the funding formula and the SEL portion of the base cost model. **This excludes federal and local dollars, various smaller state expenditures (e.g., educator licensing and assessments), and money for K–12 education not funded via ODE budget (e.g., school construction dollars and property tax reimbursements). † This includes the additional $115 million that was included in the omnibus amendment to the House budget.

The six-year phase-in of the funding increases called for by HB 110 explains the relatively small increases. While this gradual approach may have been necessary, it continues to raise questions about how the rest of the funding model will be paid for. Will future lawmakers need to raid other parts of the state budget to pay for increases, as HB 110 does with the Student Wellness money? Or are they leaving the heavy lifting—possibly raising taxes—to future lawmakers? And what happens when there are calls to re-compute the base costs using up-to-date salaries and benefits, instead of 2018 data? We’ve already heard this committee discuss the need for an additional $454 million to fund based on FY 2020 salary levels. While it might be fine to use three-year-old salary data now, won’t using FY 2018 data be a problem in FY 2026? This alone gives considerable uncertainty about how this funding model can be sustained over the long run.

***

Funding the education of 1.8 million Ohio students is an incredible responsibility, and I commend legislators in both the House and Senate for their diligent work in this area. Creating a fair, sustainable—and student-centered—funding model remains one of the most challenging areas in education policy. For the past two decades, Ohio has made significant progress in funding education, and with additional, smart reforms, we can continue to create a system that is fair, equitable, and built to last.

Thank you for inviting me to share my thoughts and I welcome your questions.

As Ohio’s General Assembly continues working on the biennial state budget, policymakers have the unique chance to pursue meaningful education reform for Ohio’s K–12 students. Given the dark rain clouds of the past fourteen months, we are all grateful to see a silver lining emerging. Ohio is currently considering the largest school funding overhaul in at least twenty years—the best opportunity in a generation to make a difference for Ohio schoolchildren and their families.

The pandemic has disrupted elementary and secondary education like nothing else in our lifetimes. Schools have been shuttered, students sent home to learn in online “classrooms,” and curricula rewritten to cope with new realities. Public school administrators grappled with the risks and complexities of reopening. Many parents have wondered how well their children were really learning in remote environments. Others didn’t have to wonder; they saw firsthand that their children were not thriving online. And parents across the Buckeye State have been forced to reconsider the pros and cons of their local public schools in ways they had never done before.

In fact, an interesting recent poll shows that 66 percent of parents with a child at home agreed that at least a portion of funding should follow students in what is sometimes called the “backpack” model.

Enter education savings accounts—often referred to by their acronym ESAs—which satisfactorily address the sentiment of those same 66 percent of parents and the unique challenges facing families in the wake of the pandemic.

As the name suggests, ESAs are special savings accounts funded with state education dollars, which are designated for families to spend on education expenses. ESA funds can be used to pay for a wide variety of educational products and services, including laptop computers and other necessary technology for distance-learning, software, online courses, private tutoring, other support services, and curriculum enhancements.

ESAs also give parents greater control over their children’s education by directly giving them additional financial resources to help pay for more personalized learning tailored for each student’s individual educational needs.

No school or system, whether public or private, has a proven silver bullet strategy for educating students during a pandemic. And no one-size-fits-all model will properly educate every child—whether there is a pandemic or not. Unfortunately, the current proposals being considered by our elected officials still fund our public school systems rather than the students they are tasked with teaching.

ESAs are more flexible than Ohio’s existing voucher programs because ESAs would allow parents to pay for more than just tuition. Rather than continue funding school systems, Ohio—like its families—should reevaluate its approach to education and education-related spending to accommodate present and future realities.

Even before the pandemic interrupted two academic years, the Nation’s Report Card warned that African American and Hispanic students, as well as students in low-income households, were suffering from persistent academic achievement gaps. The pandemic is unlikely to have closed those gaps.

Indeed, more students than we would like to admit have probably slipped through the educational cracks over the last year.

Through ESAs, Ohio could help students at every income level, of every race, and in every neighborhood of the state pay for learning that is right for them. Nine other states have pioneered ESA programs tailored to meet their students’ needs. Ohio is falling behind and should join the growing movement toward funding the unique needs of students rather than one-size-fits-all business as usual.

In the wake of this devastating once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, this biennial budget offers Ohio’s General Assembly a corresponding once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. We must reassess K–12 education and carefully design and implement an ESA program, with guardrails to ensure that funds are easy to access and appropriately spent, but without onerous burdens or bureaucratic meddling. Ohio should take a student-first approach in order to significantly improve education outcomes for students in every corner of the state. Sometimes, the hardest thing is to recognize the silver lining when it appears. The General Assembly should act now—for the sake of all Ohio students.

Robert Alt is President and Chief Executive Officer of The Buckeye Institute.