Discussions about the power of literacy are ceaseless. We acknowledge that literacy is the backbone of all learning, and we know that raising a student’s literacy abilities increases scores across the content areas (Cromley, 2009; Martin and Mullis, 2013). This is intuitive and, as a result, English language arts and literacy scores have been a part of every high-stakes accountability initiative, and funding for literacy matches that priority. We focus on and fund literacy efforts. But why does the power of our dialog and the magnitude of our investments not match our actual results?

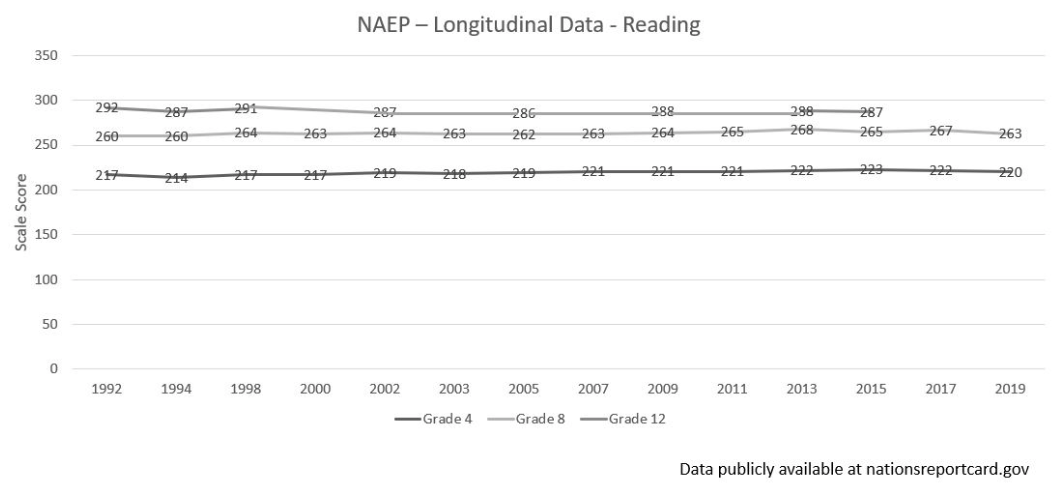

Despite being a top priority, NAEP data show stagnant proficiency rates for reading across decades (See the Figure 1). Similarly, in most states, the highest rates of proficiency are seen on grade 3 reading tests, but then fewer students are proficient by the end of grade 5, and still fewer yet at grades 8 and 10. Over the years of school, proficiency rates drop considerably and the gap between the highest and lowest performing readers gets wider.

Figure 1. National Assessment of Educational Progress scale scores, reading, 1992–2019

Understanding the predictive implications of whether a student is reading on grade level by the end of grade 3, more than thirty-five states have enacted programs designed to ensure just that, many including significant accountability measures such as retention. If proficiency on reading at grade 3 is achieved, that’s wonderful. But if students then fall behind by grade 5, grade 8, or grade 10, the race is clearly not won. As Hirsch (2006) notes, “It’s in the later grades, 6–12, that the reading scores really count because, after all, gains in the early grades are not very useful if, subsequently, those same students, when they get to middle school and then high school, and are about to become workers in citizens, are not able to read and learn.”

I am VP and Chief Academic Officer of Renaissance, a company focused on literacy and assessment tools to accelerate learning. As part of our work, we just launched a resource that lists the most essential discrete skills for each grade level based on custom-developed learning progressions for each state’s standards. Despite supposed variances between standards sets, there are some distinct commonalities. The distribution of essential skills across the grades offers some insights, and when one toggles from state to state, a consistent pattern is seen—the highest number of skills is generally (forty-three out of fifty-one instances—fifty states plus D.C.) found in grade 1.

During the first few years of school, many essential literacy skills must be directly taught. This echoes the current dialog about the research-documented need for all students to receive explicit and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, which is currently known as the “Science of Reading” movement. This area of literacy acquisition, which Hirsch (2017) refers to as “the mechanics of early reading,” is “an important gain” (2017). But what many have not come to understand is what must happen for reading growth to continue after the mechanics of reading are explicitly taught.

Though there is more we can do in the early grades, our larger problem is increasingly not with the beginning of our students’ journey of literacy acquisition. Our bigger problem is the later grades where reading growth flatlines. In these years, the number of skills drops substantially. We have less that we must directly teach to students, but there is much more that must be done with them.

This is because “after one has learned the mechanics of reading, growth depends, more than anything, on our ability to build up students’ knowledge base and vocabulary” through wide reading (Lemov, 2016; Pinker in Hirsch, 2016; Shanahan, 2011, 2014; -- as cited in Schmoker, 2018, pg. 27). This is why the Common Core places so much emphasis on text quality and complexity, and also calls for us to “markedly increase the opportunity for regular independent reading of texts that appeal to students’ interests to develop both their knowledge and joy in reading” (CCSS).

In the first phase of literacy acquisition, much must be directly taught to students (e.g., phonics skills). After they acquire these skills, they actually “self-teach” through extensive reading and exposure to text, assuming we create the time and conditions (Share, 1995; Share, 1999; Fogarty, Kerns, and Pete, in press). As Schmoker (2011) notes, “once students begin to read, they learn to read better by reading—just reading—not by being forced to endure more reading skill drills.”

Hirsch (2017) boldly states that “once decoding has been mastered and fluency attained, relevant knowledge becomes the chief component of reading skill” and asserts that “every cognitive scientist specializing in the subject would agree with that statement.” He argues that developing students “knowledge is by far the most promising avenue to carry us out of the reading slump we are in” and claims that schools must “realize that the secret of answering [the complex questions of today’s high stakes tests] will not be hours of practice of ‘inferencing skills’ and ‘close reading skills’ but can only be answered through the student’s prior relevant knowledge of words and topics” (Hirsch, 2017, pg. 30 – emphasis added).

The role of knowledge in reading comprehension is critical to consider because, as Willingham (2017) notes, writers “judge what their readers already know and what must be made explicit in the text, and write accordingly.” If readers have the assumed information, comprehension occurs. If not, all meaning can be lost. Consider the following simple sentences and the knowledge they assume:

- It was a herculean task.

- They reacted like Pavlov’s dogs.

- That became her Waterloo moment.

- You’re charging at a windmill.

Our challenge, then, becomes not only teaching the discrete literacy skills that students need—primarily in the early years—but also the general knowledge that writers assume. What are the names, dates, places, people, and ideas that students need to know to be literate in the world? This knowledge needs to be part of our curriculum as well. Is it? Too often, knowledge is not as thoughtfully considered as various skills. Until such time as it is, our literacy scores will remain a flatline.