For years, empirical research has emphasized the importance of student engagement, yet the education research world spends little time focusing on young people’s perspectives. Last year, to amplify the voices of students, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute published What Teens Want from Their Schools, which commissioned a survey asking high schoolers about their classroom experience. Its results painted a broad portrait of student engagement, as well as how their view America’s education system.

To mark the beginning of the new school year, on September 14 we published the first in a series three blog posts examining those results. It explored how young people feel about different activities, from teacher lectures, to group projects, to student presentations. (The general answer? Not very enthusiastic, but it depends on individual teachers and classrooms.) This is the second in that series, and it looks at what students say about their own approaches and attitudes toward school.

Students aren’t passive receptacles of education “content,” no matter how exciting the lesson; their active inputs, like effort, persistence, and other positive habits, are just as vital to engagement and learning. As Michael Petrilli and one of us pointed out recently in Education Next, “When students work harder, they learn more.” Yet student effort is frequently, and mistakenly, overlooked by reformers, who treat it as an output—a natural result of better teachers and schools—rather than an input from students. In reality, it’s both, and a key piece of the engagement puzzle. So what are teenagers bringing to the table?

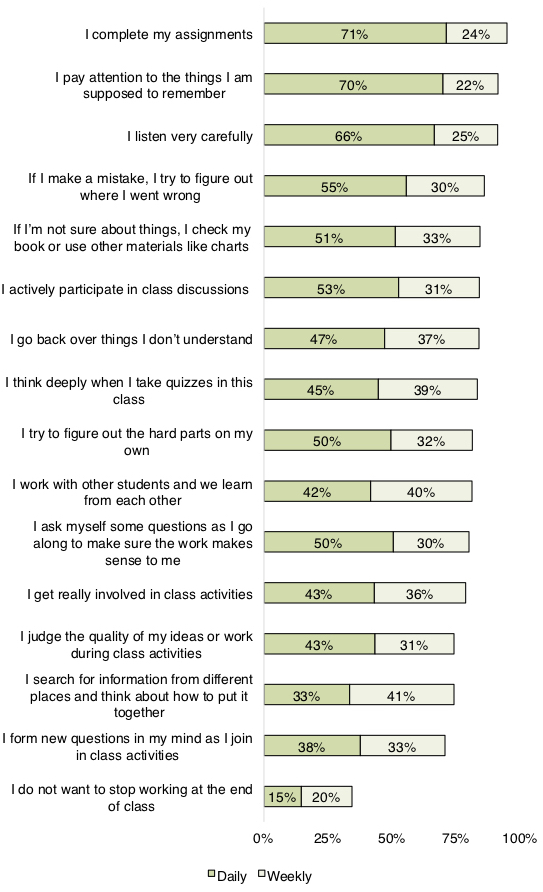

With that in mind, Fordham asked students nineteen questions on how they think about studying and classroom work. These survey questions include self-ratings of cognitive experiences (e.g., “I try to figure out the hard parts on my own”), behaviors (e.g., “I complete my assignments”), and classroom effort (e.g., “I listen very carefully”).

The results show—surprise!—that teens are inconsistent, with a wide difference between daily and weekly behavior. For nine out of sixteen positive practices, less than half of students say they exercise the behavior on a daily basis, but for fifteen of the positive practices, over half of said they exercise the behavior at least weekly. And as figure 1 shows, 90 percent report that they listen carefully, pay attention to the things they are supposed to remember, and complete their assignments. (But the news that over one-fourth of that group does those things weekly rather than daily isn’t exactly heartening.)

Figure 1: Over half of students say they exercise most positive behaviors at least weekly

Another less-than-shocking result is that students admit to often doing much less than their full potential. One in four (26 percent) reports frequently pretending to work, while half admit to frequently letting their minds wander, and almost a quarter say they do so daily. (See figure 2.) The fact that so many students are putting in less than 100 percent might help to explain why NAEP results are so disappointing, and why 40 to 60 percent of first-year college students require remediation.

Figure 2: A quarter of students report pretending to be working daily or weekly

The truth is that the results raise more questions than they answer. Why pay attention some days, but not on others? Is the difference made by the teacher, the subject, the activity, or something more personal, like hours of sleep or whether a distracting friend is in class? The data don’t tell us.

What we do know (what teachers already knew) is this: There are a lot of students who are phoning it in at least some of the time. While many students are working hard, a good number admit to faking work and frequently zoning out—and there’s substantial overlap between those groups. Some of the students who “listen very carefully” daily or weekly are also those who say they let their minds wander daily or weekly. So how can we convince those part-time listeners to participate fully in their own education?

That question brings us back to engagement, which we already know is an area for growth. Notably, the only positive learning experience that less than half (34 percent) of the students report having weekly was the one that asked about their feelings rather than about their behaviors: “I do not want to stop working at the end of class.”

To expect disengaged high school students to somehow morph into college-and-career ready graduates is simply unrealistic. As important as curricula, materials, standards, facilities, teacher training, and a hundred other factors in education may be, we cannot expect that, even if all those things were magically solved, student engagement—and effort—will just fall into place.