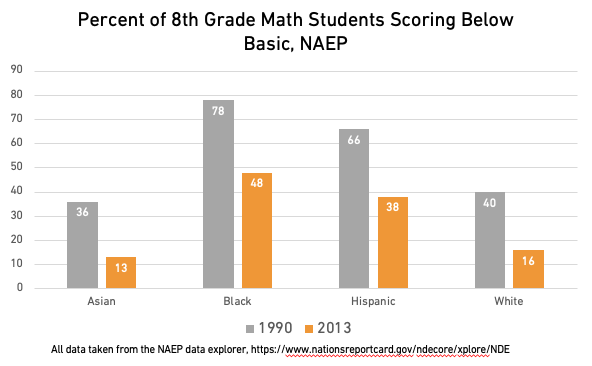

In 1990, 48 percent of our nation’s eighth graders had very weak math skills. How did we know? They scored in the lowest performance category, Below Basic, on the national test given to a sample of American students every two years.[1]

By 2013, something remarkable had happened. The share of eight graders Below Basic was just 26 percent.

Even better, the progress was shared across every demographic group. For example, the percentage of Black students with Below Basic scores dropped from 78 to 48 percent.

It was an incredible victory for American schools. Fewer struggling math students meant more opportunities to complete advanced coursework, qualify for good jobs, and earn higher wages.

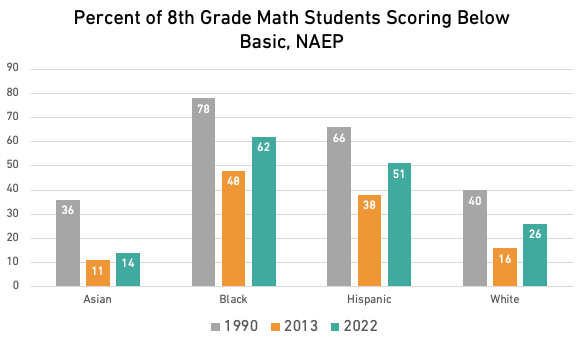

Unbeknownst to us at the time, 2013 turned out to be the high-water mark. Achievement stopped improving. First, it stagnated. Then, toward the end of 2010s, it began to decline. And finally, along came Covid.

Below, you can see the picture as of 2022. The share of low performing math students increased compared to 2013 for each racial group—with especially large jumps for Black and Hispanic eighth graders. Much of the progress from the earlier period eroded.

Why did this happen?

Short answer: No one seems to know.

This goes far beyond the pandemic

We’re in the midst of an education depression. By depression, I mean an extended era of shrinking outcomes and opportunity. I hesitate to call it a “great” depression because that feels hyperbolic. But the duration—over a decade already—makes the term plausible.

I’m not the first to describe this problem. Mike Petrilli and Chad Aldeman are just a few of the policy-world voices who have been sounding the alarm for years. Journalists have covered it. In the past month alone, Kevin Huffman wrote about it in the The Washington Post and Jessica Grose of The New York Times generated chatter by calling it the crisis that neither presidential candidate has a plan to address.

But due to a generalized stance of denial in the public sphere, this is still news to many people. If that’s true for you, don’t feel bad. Plenty of education conversations at the state and local level revolve narrowly around recovering from Covid learning loss—as if it would be a momentous victory to return to 2019 achievement.

Wrong. Our true problem is larger. For more than thirty years, education indicators almost uniformly got better. We occupied ourselves by arguing (sometimes aggressively) about whether they were improving fast enough and whether marginalized students could close gaps entirely with more privileged students.

Those debates are no longer happening. Why? Because we’re moving in the wrong direction. Who wouldn’t love to return to the good old days when our biggest grievance was the velocity of our victory? It’s now become easier to ignore the big problem than to fix it.

Is there any evidence of this so-called “depression” beyond national test scores?

Yes, loads of it.

- Absenteeism. Longtime readers remember that I covered this issue in detail last fall, and there’s still regular mainstream news coverage, so I’ll spare you a lengthy recap. At its core, absenteeism reflects disengagement from school on the part of students and families. In 2014, just 14 percent of students were chronically absent. In 2023, it was 26 percent. Figures are up in every single state that measures absenteeism.

- Higher education. Participation in college has moved steadily in one direction—up—for pretty much the entirety of American history. Until recently. In 2012, 41 percent of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds had enrolled in a two- or four-year school. In 2022, enrollment declined to 39 percent. That drop is small, but dig beneath the surface and there are surprising trends. Enrollment in two-year colleges was down 34 percent over the decade, with declines particularly driven by White students, who are more likely than peers to express skepticism about the quality of education colleges are offering. The FAFSA debacle has further depressed enrollment. Views of higher ed have split along partisan lines. A college crisis is brewing.

- Reading. Let’s put achievement aside for a moment. We prioritize literacy among elementary students partly to create lifelong, passionate readers. How’s that going? In 2012, 27 percent of thirteen-year-olds reported that they read for fun “almost every day.” By 2020—in surveys taken before the pandemic—the figure had dropped to 17 percent. That’s a big change in eight years. For the first time since the survey was launched in 1984, the share of kids who “never or hardly ever” read for fun—29 percent—exceeded the share that reads almost every day.

Make a list of educational outcomes that matter to you personally. Then look up whether those measures were better for your local community in 2013 than they are now. I’m willing to bet you’ll see much the same pattern.

Why does this depression attract so little notice?

There was an era from the 1980s until Barack Obama’s second term characterized by heightened national attention to learning standards, school improvement, choice, and test-based accountability. Almost everyone uses the same term for it: education reform.

This past decade—which has been seen a shift away from reform priorities in addition to falling performance—has no name. It’s the nameless depression.

When I ask folks about this, they bring up a few dynamics:

- Losses were concentrated among low-performing students. We have roughly the same number of high-performers on national tests as a decade ago. Far more students are receiving perfect scores on the ACT exam. Elite colleges are awash in qualified applicants. At the same time, we have more struggling students—and their achievement levels are noticeably lower than was the case for strugglers in 2013. Old gaps have re-opened. But elite, affluent communities with highly educated (and influential) populations have been substantially spared.

- We can blame COVID. In some respects, this is reasonable. Learning setbacks related to the pandemic were enormous and lasting. But it’s misleading to suggest that our educational downturn began when schools sent kids home in March 2020. The depression was well underway. Covid only exacerbated it. We can’t use Covid as a permanent get-out-of-jail-free card. Nor should public officials over-celebrate small gains that only cement our anemic recovery.

- Test scores lost credibility. Data showing declining achievement have been clear and publicly available. But in the wake of the reform movement, nobody wanted to discuss it. In the 2010s, teachers unions and fed-up parents waged war on testing—nearly succeeding in removing the federal requirement to assess students annually in math and reading.[2] Additionally, almost every state changed its tests—some more than once—during the transition to new learning standards. It was difficult to compare results from one year to another. The construction dust led observers to overlook a national pattern.

- There were conflicting signals. Not every indicator has deteriorated in the past decade. High school graduation rates, for instance, have climbed significantly, from 80 to 87 percent. Hard to complain about good news. But graduation rates are almost entirely controlled by local schools. If they relax expectations and inflate grades—which is exactly what researchers find they’ve been doing—graduation rates will rise even if students are performing worse. Academic leniency has papered over learning deficits in many communities.

What now?

The original Great Depression ended when the American economy mobilized for World War II. We can’t wait around for a geopolitical event to fix this mess. We need leadership.

Some things for us to do:

- Acknowledge reality. It’s time to stop pretending. This applies to everyone—not just education officials. Funders and non-profits are just as guilty of hiding out in recent years. I’m on the email distribution list for dozens of organizations. Most of them never mention the crisis we’re in. It’s long been fashionable to say we are “data driven,” but the past decade suggests that’s a hollow claim. Having the wrong frame for our situation has prevented us from setting the right course.

- Resist the urge to find a simplistic scapegoat. Remember, our declines are evident in all fifty states. There is no national conspiracy to deliver poor results. Schools have focused on the priorities we’ve given them in the best ways they know. We can’t write off long-term trends to hot-button issues—like book bans or DEI initiatives—that draw big heat in a handful of places. My concern is that we have not been clear with schools about what’s most important and we have asked them to focus on too many things outside their core competence.

- Brace ourselves. In just a few months, we’ll have a new president and another round of NAEP results. We don’t know whether we’re about to see signs of hope or new reasons for despair. Based on state test scores released for 2023–24, I am not optimistic about big gains on NAEP.[3]

- Pass a new federal education law. The Every Student Succeeds Act, enacted in 2015, has been a dismal failure. It is wholly unsuited to our present challenges. We need bipartisan congressional leadership to develop a successor for the new era. Where will that leadership come from?

- Stop playing small ball. In the face of this depression, it often feels like our available solutions are piecemeal. Let’s start by establishing clear goals. Where will we be in 2030? 2035? And how big must our ideas be to get us there?

Next month, I’ll accept my own challenge and offer a few possibilities. Thanks for reading.

Editor’s note: This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

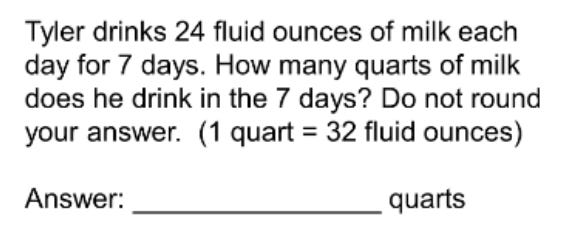

[1] If you are curious to learn more about what “Below Basic” means, the good folks from NAEP have you covered here. One of the examples they provide is below. Just nine percent of eighth grade Below Basic scorers answer this item correctly:

[2] This is ongoing. On election day, the Massachusetts Teachers Association is likely to succeed in passing a ballot resolution to remove the requirement that high school graduates pass exit exams.

[3] Here are roundups of state results for New York, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Texas, Oregon, Arizona, and Maryland. The general trend is slight improvement year-to-year, but most states remain below 2019 performance levels—particularly for low income students.