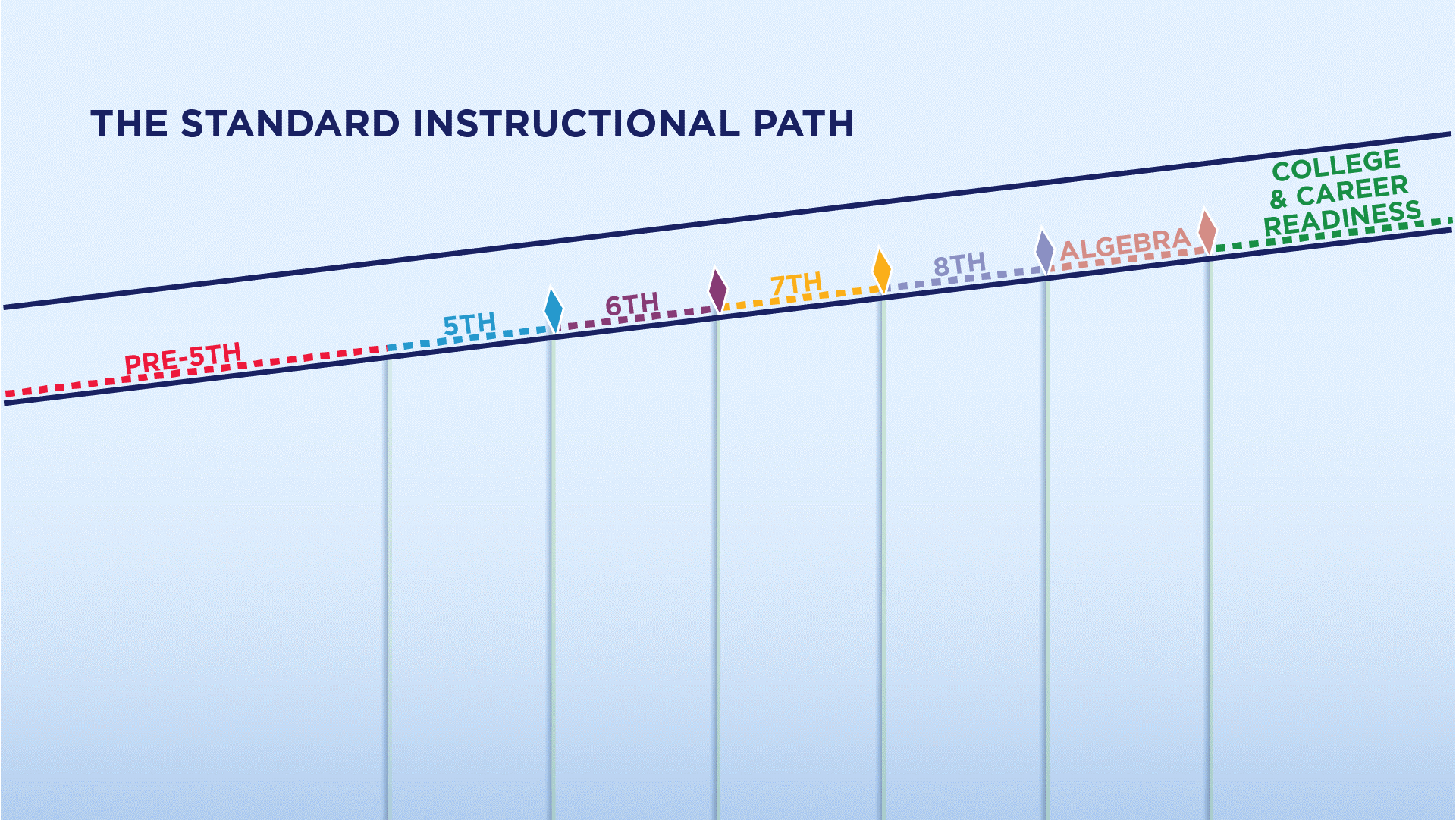

Standards are written to reflect the instructional path that students should follow throughout their educational journey. In math, that includes concepts such as basic algebraic thinking in the early elementary grades, multiplying fractions in the fifth grade, working with ratios and rates in the sixth grade, and so forth. Let’s call this the “standard instructional path.”

At the end of each school year, students take a state summative assessment (marked by the filled diamonds in the chart below) that reflect student performance relative to the current year’s standards.[1]

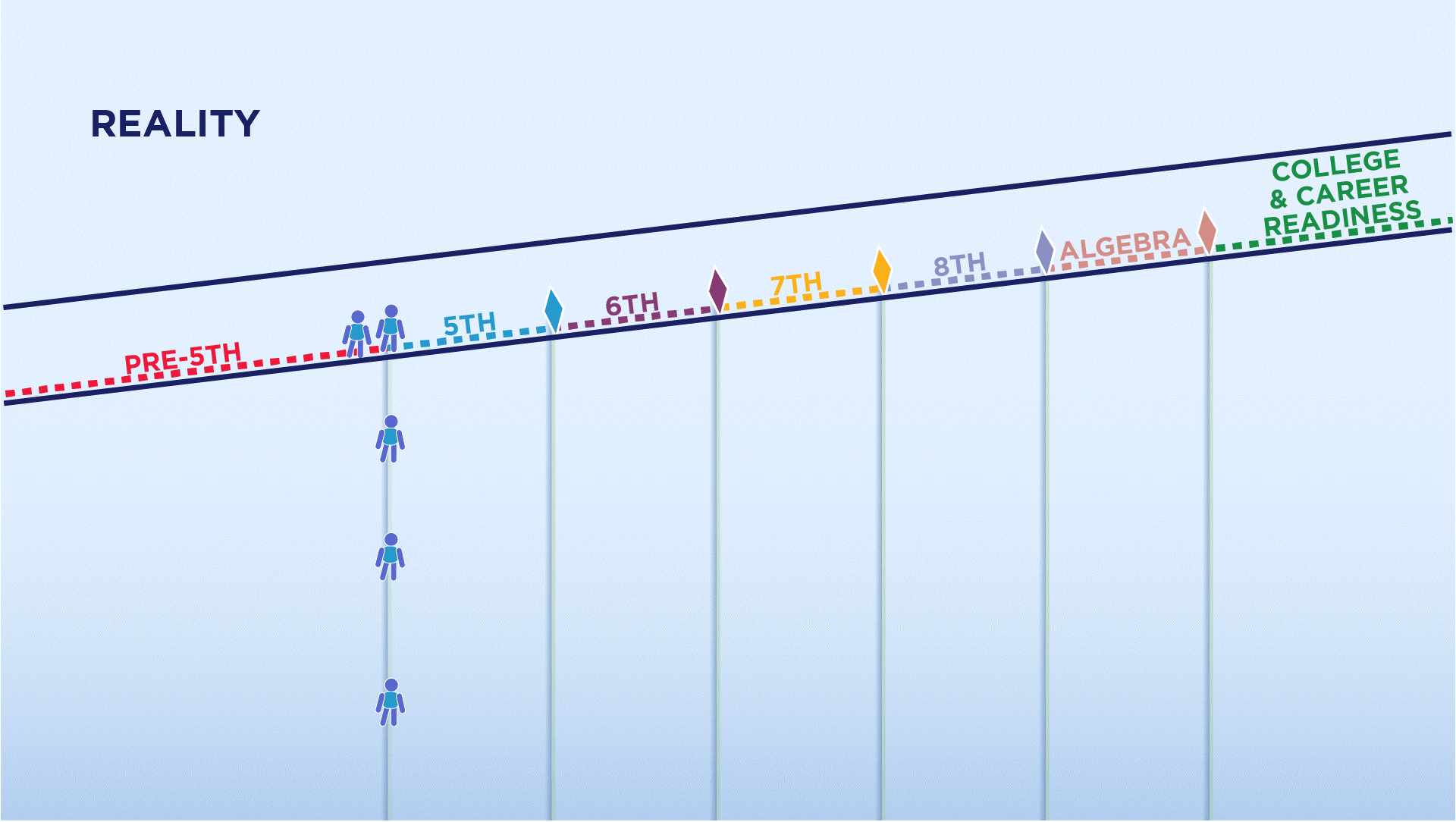

While the standards themselves are clear and coherent, they provide little guidance about what to do for the millions of students who begin the school year without the precursor knowledge required to succeed with grade level material. This is especially problematic in math, given it’s so cumulative. A student is going to have a hard time learning how to calculate the area of a circle if they haven’t yet mastered multiplication.

Since only about two in five students begin fifth grade on the standard instructional path, how should schools best address the strengths and needs of students with unfinished learning dating back to elementary school?

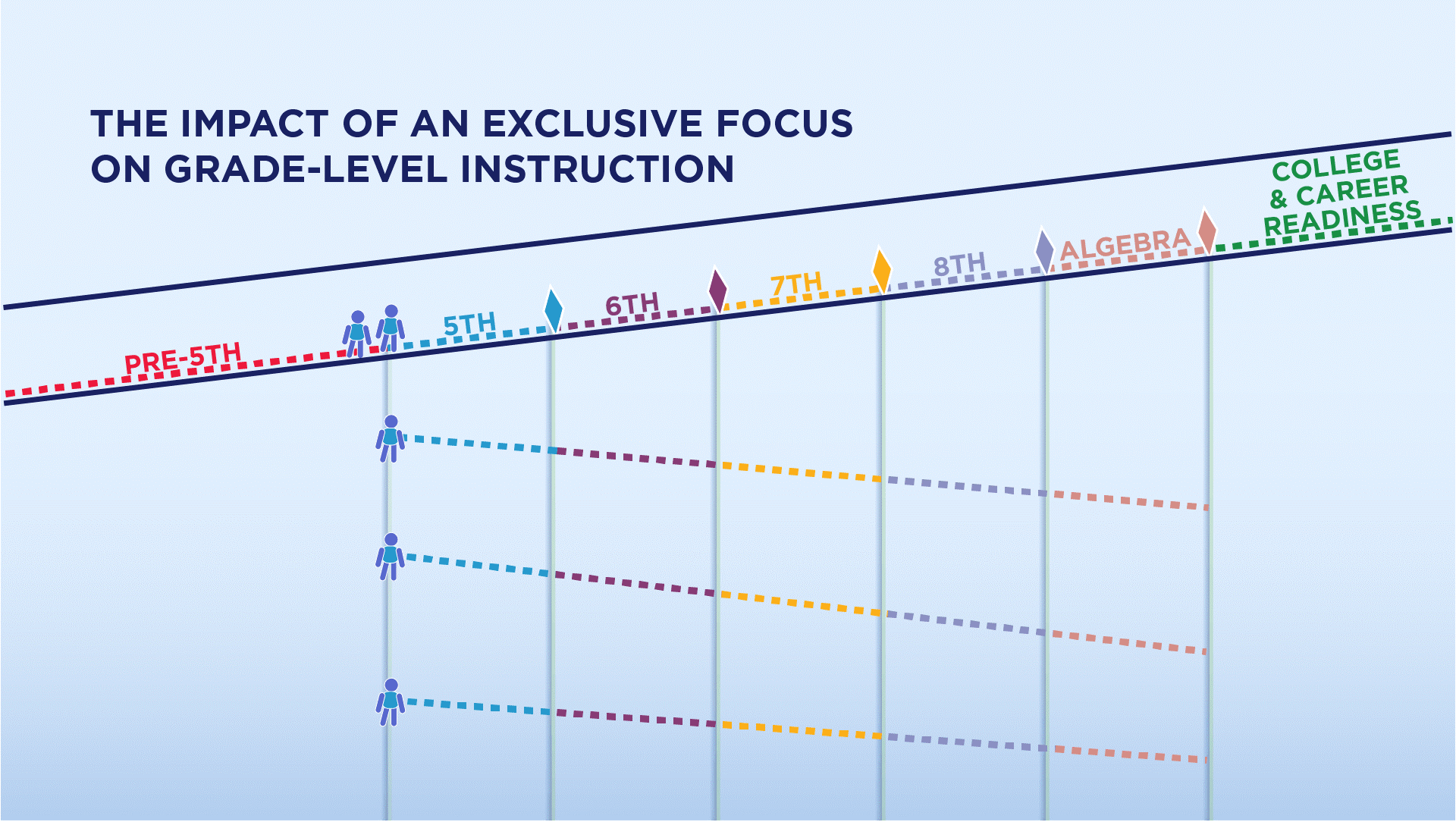

Some argue that good teaching is enough to get students caught back up. They insist that high-quality teachers with expectations focused on grade-level material can always find ways to get students back on the main path. This belief is essentially cemented into federal and state education policy, as accountability systems are based on grade-level assessments.

But in math, there’s not much evidence to suggest catching them up in a single year is practical—certainly not at scale. Not only have researchers shown the probability that schools can pull this off to be remarkably thin, but there’s mounting evidence that in trying to do both, students are falling further behind (see The Iceberg Problem).

That doesn’t mean that educators should simply meet students where they are. Growth only matters if it is in service of college and career readiness. In some situations, “meet them where they are” can become a proxy for perpetual remediation, particularly for historically disadvantaged student populations. Expectations matter, and there’s no doubt far too many students attend schools that simply don’t expect enough.

But in math, an exclusive instructional focus on grade level content that ignores students starting points is not the solution either. That approach is more aligned with equality than with equity.

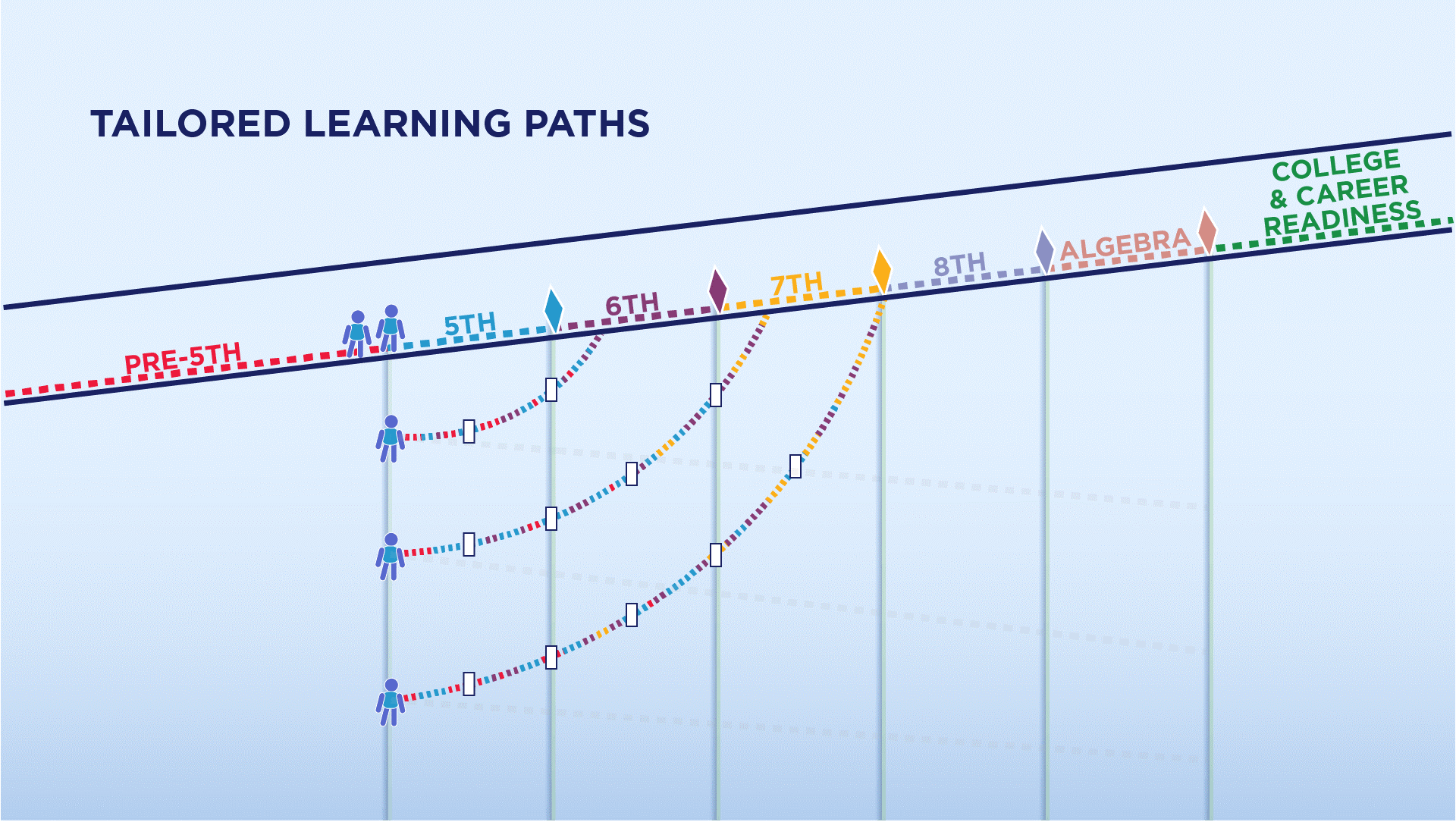

What’s instead required is the development of tailored paths—customized instructional programs that combine pre-grade, on-grade, and (in some cases) post-grade skills in order to connect where students are to the standard instructional path. For some who aren’t as far behind, these tailored paths may take a single year. But for those who are multiple years behind and who aren’t able to access more instructional time, they may need a bit longer. In all cases, schools would then need assessment and accountability systems that are aligned with each student’s unique path to get there (the white rectangles below).

Through our work with Teach to One: Math, we’ve been piloting these kinds of tailored learning paths for several years. In some partner schools, we had the freedom to implement this approach with fidelity because those schools operated under local accountability systems tied to student learning growth on adaptive, multi-grade assessments. But in others, schools pressed us to ensure more “standard path” instruction than we would have recommended because of concerns around grade level assessment and accountability.

What’s worked better?

According to a third party study of all three-year implementations (with an n of 739 students), programs that operated under accountability systems tied to learning growth improved 38 percentile points, while those more focused on ensuring exposure to grade level content grew 7 percentile points. In growth-aligned schools, that corresponded to an improvement in the percent of students on a college ready trajectory from 19 percent to 40 percent. In schools that prioritized more grade level exposure, the percent of students on a college-ready trajectory still improved, but not as much (12 percent to 22 percent).[2] In one district, ongoing efforts to both meet students unique needs while also prioritizing grade level exposure ended up with a muddied implementation and an indeterminate evaluation.

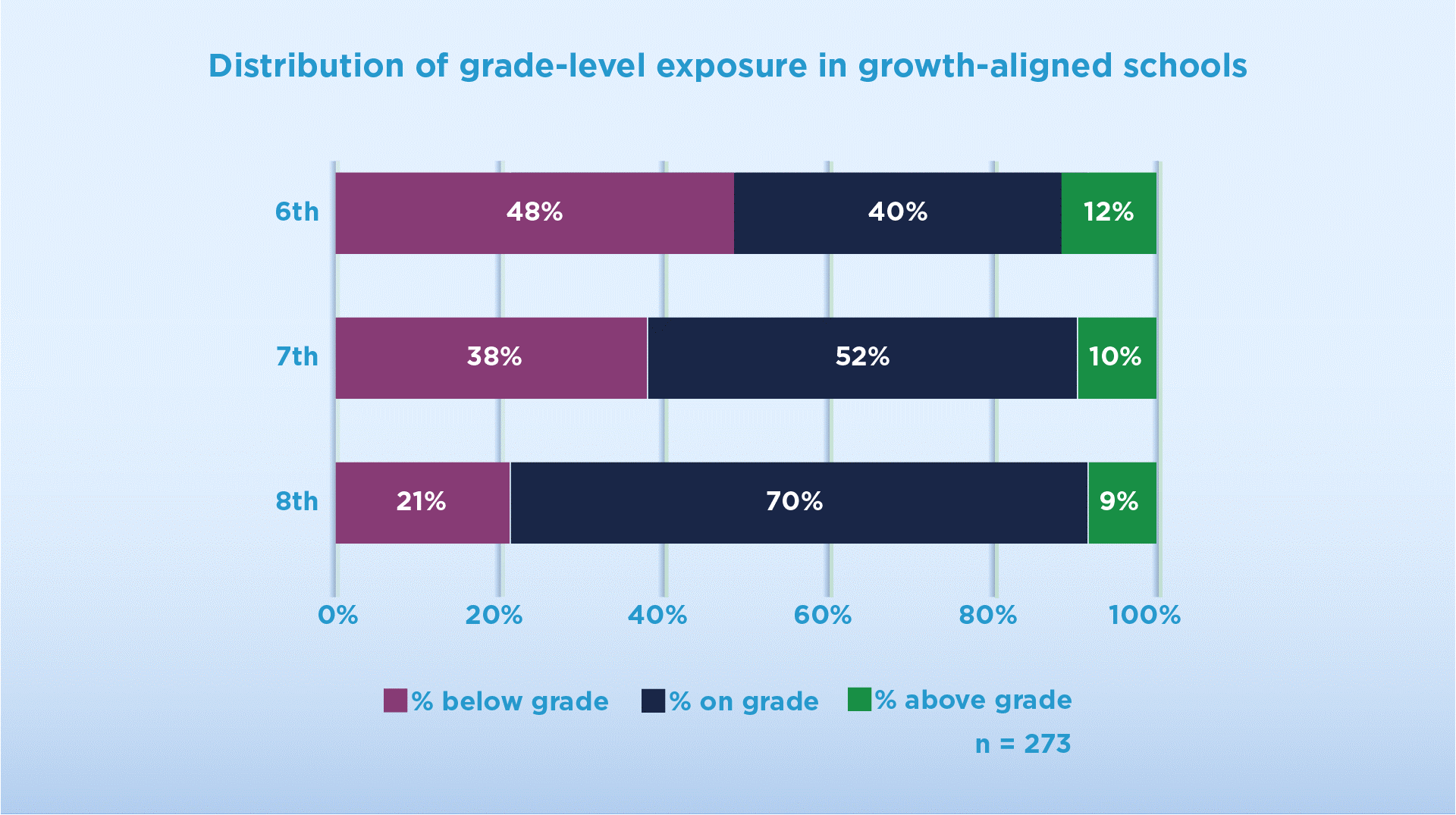

And it’s not as if students who began middle school far below grade level spent all of their time on pre-grade material. The chart below shows how the distribution of pre-grade material declined over time in those schools focused on learning growth.

More research would be required before we can conclusively determine that tailored learning paths are more likely to drive long term proficiency. But given both its early promise and the evidence that a focus on grade-level material may be causing students to fall further behind, how might our national K–12 strategy include efforts to foster the development of these kinds of tailored learning paths?

The first step is to recognize that tailored learning paths require a different way to think about accountability that’s less focused on annual grade level assessments. Policymakers should not retreat from insisting upon high expectations for all students, but must also find ways to create space in policy for tailored paths that span multiple grade levels to emerge. Texas’s work around Math Innovation Zones is an early example worth following.

But more importantly, tailored learning paths aren’t likely to develop within the traditional model of schooling. Schools can’t simply train teachers to diagnose each student’s unique strengths and needs and then build and implement a tailored path—all within the confines of their classroom. It’s just too far beyond the scope of what any single teacher can reasonably accomplish.

That’s why innovative learning models that break from traditional notions of whole-class instruction are so essential to addressing the needs of students who are multiple years behind where they should be. Our nation has lived with the same basic delivery model of one-teacher-thirty-students-in-a-box-with-a-textbook for more than a century. It’s time to modernize it.

Innovative learning models can now be designed in ways that integrate research, teacher talent, practical know-how, and (yes) technology so that schools can better organize meeting each students’ unique strengths and needs. They could also solve for other important objectives, such as social and emotional development, more opportunities for parent involvement, more authentic learning experience for students, and more controls that minimize racial and ethnic biases in the classroom. These worthwhile endeavors are far more likely to succeed if they are embedded within thoughtfully-designed learning models, rather than being one more thing for teachers to get trained on and then figure out how to execute.

Here’s a bit about the model that we’ve built, but we need others to emerge as well. With the right incentives, today’s charter management organizations, publishers, product companies, universities, and others could all compete to design new models that replace textbooks as the core “technology” used in schools today. And in exchange for supporting the R & D to develop them, the model providers themselves would do something that today’s textbook companies generally don’t do—share in the accountability for student outcomes.

Leveraging serious R & D to drive improvement in our nation’s schools has not been a core element of reformers’ playbook over the last few decades. Meanwhile, over $100 billion of R & D over the last decade has helped to double our national output or renewable energy while reducing coal to its lowest level in more than a generation. In health care, R & D is what’s fueled the development of new ways fight disease and improve and prolong quality of life. In defense, R & D is what’s enabled our forces to rely upon military strategies that put fewer American lives at risk on the battlefield.

Future generations will wonder why it took our sector so long to move in this same direction.

The best way to support students who are multiple years behind is to design adoptable, innovative learning models that are organized do just that. Absent that, the profound limitations of the traditional classroom model make it highly unlikely that the tailored paths they require can ever be reliably provided.

[1] Note that advanced students are able to progress through algebra by the end of the eighth grade and take the algebra state assessment rather than the eighth-grade state assessment.

[2] Based on MAP Growth College Readiness Benchmarks study linking performance on MAP to the trajectory required for achieving on ACT score of 22.