Editor’s note: This was first published by The 74.

Just before the winter holidays, the National Center for Education Statistics released new data on school staffing in the 2021–22 academic year. The data are provisional, but they represent the best look yet at how school staffing levels have changed over the course of the pandemic.

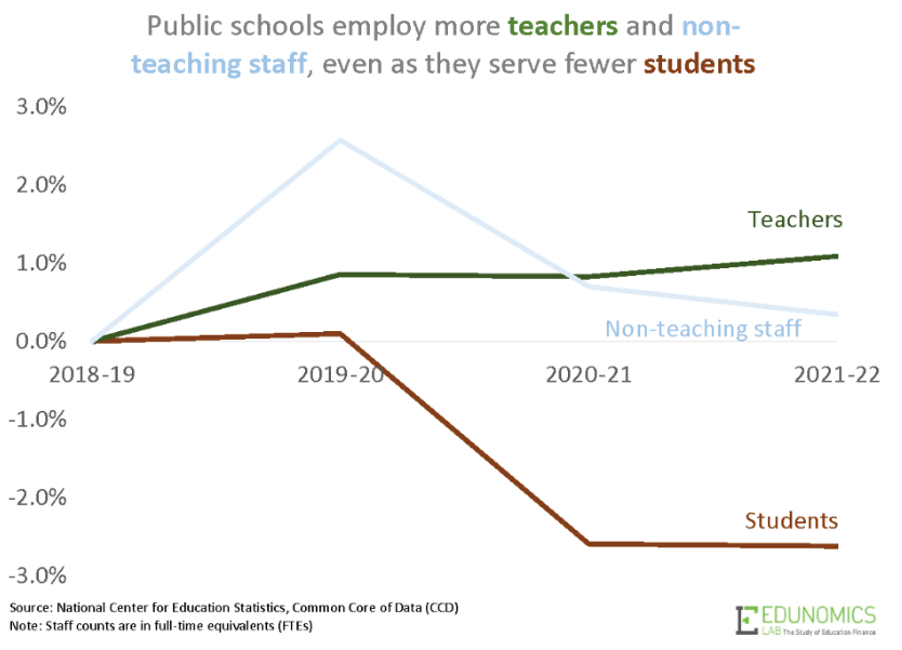

As I forecast in September, the new data show that schools have been adding teachers, even as they serve fewer students.

The first graph below tells the national story. Student enrollments (in red) fell in the first full year of the pandemic and have not recovered. In total, student enrollments in public schools are down 2.6 percent (1.2 million) from the 2018–19 academic year. Meanwhile, those same schools employed 32,000 more teachers (a gain of 1.1 percent, in green).

There was a very small dip in the number of teachers from 2019–20 to 2020–21 (a decline of .03 percent nationwide), but that has since reversed, and the U.S. is now safely above pre-pandemic levels.

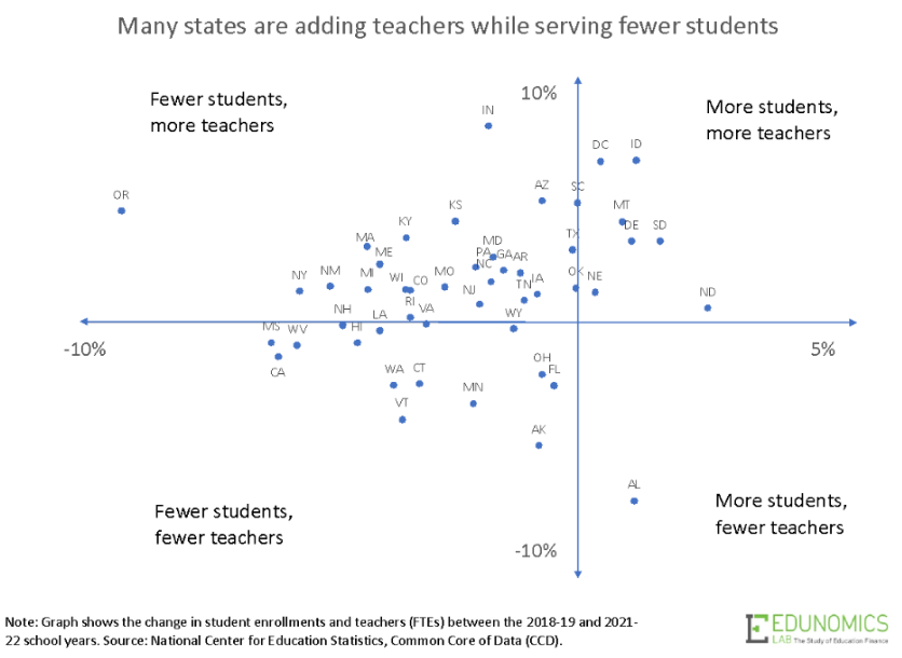

There’s wide variation across the country, but public schools in many states have been adding teachers while serving fewer students. The next graph compares the change in student enrollment versus the change in the number of teachers by state from the 2018–19 to the 2021–22 school years. Complete data were available for forty-seen states and Washington, D.C.; of those, forty had a lower pupil/teacher ratio last year than they did in the last year before the pandemic. Data for all years aren’t available yet for three states—Illinois, Nevada and Utah—but they also appear to be lowering their student/teacher ratios.

The new NCES figures are from last school year, but they help answer some questions that other federal datasets can’t address. For example, according to the latest payroll figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in public K–12 schools is still down somewhat from February 2020.

The bureau’s data are the timeliest available, but they can be somewhat misleading in that they count each individual employee regardless of how many hours they work or in what role they serve. So a school with fifty full-time and twenty half-time employees would count as having a total of seventy.

The NCES data more accurately reflect a school’s total available staff time because they are calculated in terms of full-time equivalent employees (FTEs), which takes into account the number of hours an employee works. Two half-time employees equal one full-time worker, so in the example above, NCES would count that school as having sixty FTEs (fifty full-time plus twenty half-time employees). According to the NCES data, public schools nationwide employed 65,000 fewer FTEs last year, or about 1 percent less than their pre-pandemic total.

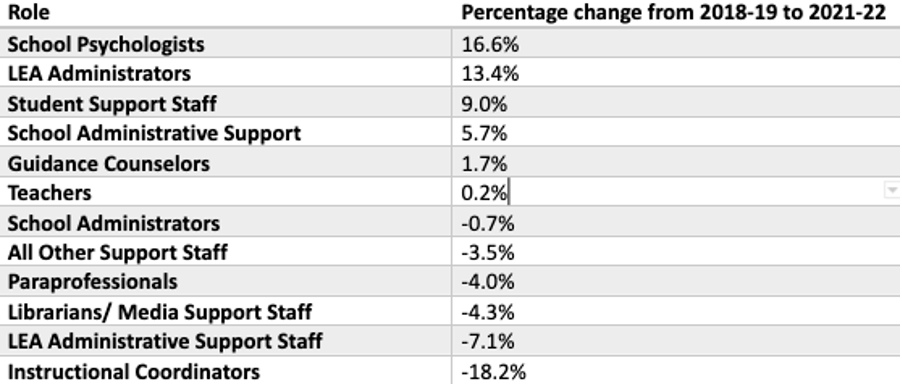

But the NCES data also allow researchers to unpack employment changes by role. In addition to more teachers, schools now employ more student support staff, a category that includes attendance officers and providers of health, speech pathology, audiology, or social services. The number of school administrative support staff, guidance counselors, district administrators, and school psychologists are also all above pre-pandemic levels.

So which types of employees did schools lose? In numeric terms, the categories with the biggest declines are paraprofessionals (down 34,000 FTEs) and a group of workers NCES classifies as “all other support staff.” This is the second-biggest category of workers in schools, after teachers, and it includes plant and equipment maintenance, bus drivers, security, and food service workers. Schools had 41,000 fewer FTEs in this “other” category of workers, thanks in part to a massive hiring slowdown in spring and summer 2020 and continued school closures well into the following academic year.

These gaps can force the remaining employees to take on additional responsibilities. That may be a big reason why teachers are reporting higher workloads and anxiety, and why they’ve been asked to fill in on other non-teaching tasks.

However, to help schools to improve their services and be responsive to student needs, it’s important to be precise about the exact staffing challenges schools are facing. Contrary to warnings of a mass teacher exodus or a nationwide teacher shortage, policymakers should remain focused on local context, specific shortages, and potential solutions to address schools’ actual needs.

Written and published while the author was with Edunomics Lab at McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University.