The data are out, and as everybody now knows—and as Mike Petrilli foresaw—they’re pretty grim. Here’s the short version, straight from the National Center for Education Statistics:

Grade 4 mathematics scores improved between 2022 and 2024, a two-point gain that follows a 5-point decline from 2019 to 2022.... Eighth-grade scores in mathematics showed no significant change.

The most notable challenges evident in the 2024 data are in reading comprehension. Reading scores dropped in both fourth and eighth grades since 2022, continuing declines first reported in 2019, before the pandemic.... In 2024, the percentage of eighth-graders’ reading below NAEP Basic was the largest in the assessment’s history, and the percentage of fourth-graders who scored below NAEP Basic was the largest in twenty years.

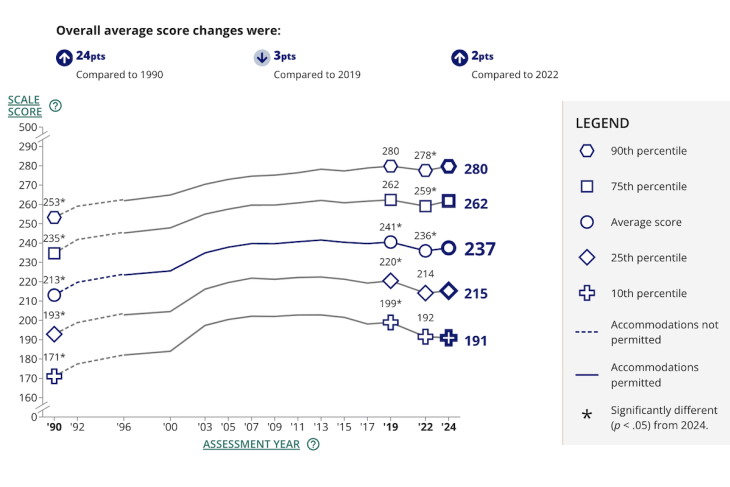

In eighth grade, the data also show widening gaps since 2022 between higher- and lower-performing students as higher performers regained ground lost and their lower-performing peers continued to decline or show no notable progress.

In eighth-grade mathematics, this widening gap is most pronounced. Lower-performing students declined, while higher-performing students improved. As a result of this divergence in performance, the average score in 2024 was not significantly different than in 2022.

In fourth-grade mathematics, the gap also grew as the scores of the lowest performing students did not change significantly from 2022, while the highest performing students’ scores increased.

In reading, lower-performing students struggled the most. At both fourth and eighth grades, the scores of students at the 10th and 25th percentiles in 2024 were lower than the first NAEP reading assessment in 1992.

As usual, the Nation’s Report Card contains a vast trove of information, both national and state-level, that analysts will pore over for years to come, and like the blind men’s elephant, one comes away with different impressions of what’s going on depending on what part of the report one focuses on and what one is comparing, especially what previous years are chosen for comparison.

Meanwhile, though, the University of Washington’s Dan Goldhaber, not known for overstatement, told the Washington Post that “I don’t think this is the canary in the coal mine. This is a flock of dead birds in the coal mine.”

Others, perhaps especially state leaders, feel the need to put a cheerier spin on their NAEP results. In Maryland, where I live, the State Board of Education took satisfaction from how the Old Line State has improved its rankings vis-à-vis other states. In eighth grade reading, for example, it rose from twenty-fifth to twenty-first, while admitting that “results have not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels.” (To me, what’s more consequential is that one full third of Maryland eighth graders remain “below basic” in reading and only one third are “proficient”. What does that portend for a state’s future?)

Much of this week’s NAEP talk is about widening gaps between high and low achievers—and there’s no denying that a flat average can (and does) mask gains in the upper levels and losses down below. We see a lot of that in the new results and of course it’s worrisome. So, too, is the overall failure—so far—of America’s obsession with “science of reading” in the early grades to arrest the decline in fourth grade reading scores. (The Maryland average is up from 2022 but far below all prior years—as 41 percent of the state’s fourth graders remain “below basic,” which is to say basically illiterate.)

Also getting much jabber—of course—is how weakly the country as a whole has “recovered” from the dire effects of pandemic school closures—especially considering how much extra money was poured into schools to counteract those effects.

Yet journalists, analysts, and politicians alike will remain frustrated by NAEP’s inability to explain why scores are where they are and have or have not changed. Like most report cards, this one describes the patient’s present condition. It supplies no diagnosis, much less a comprehensive discussion of causation. Which leaves everyone free to speculate, theorize, and pontificate. A favorite explanatory candidate for 2024’s dire performance is chronic absenteeism, perhaps combined with phones and screens and the fact that few kids today can be spotted just “reading a book” in their spare time.

Personally, I ascribe much of the mess to America losing interest in standards and accountability—and our national leaders’ neglect of educational achievement as a national priority. After four consecutive presidents for whom this was a priority, for example, we’ve now had two in a row—and likely now commencing a third—who were (to my knowledge) never heard to utter the words “academic achievement."

But maybe that’s just me.

The head-scratching, soul-searching, gut-spilling, and blame-casting will surely continue for many months to come—and it’s a fine thing at least to have this great big problem back in focus. Yet I don’t expect it to prove a “Sputnik moment.” We won’t find a consensus, we probably won’t do much more about it than we’ve been doing, and everyone’s attention will gradually shift back to their private issues, the craziness in Washington, and the menacing world outside.

N.B.: All of this is about grades four and eight. This Report Card tells us nothing about what’s happening in the high-school years. We last saw those scores in 2019, at which point 30 percent of twelfth graders were reading below basic and just 37 percent were at least proficient.