“I wish I could say this hate began with Donald Trump and will end with him,” former Vice President Joe Biden said on Tuesday. “It didn’t and it won’t.”

It’s true, of course, that racism and hate are nothing new, and the same surely goes for the partisanship and polarization gripping our nation. The culture wars are generations old, and the current season of attack and outrage opened with the dawn of social media platforms, not in 2016. We all abhor it and yet cannot seem to escape it, except in fleeting moments.

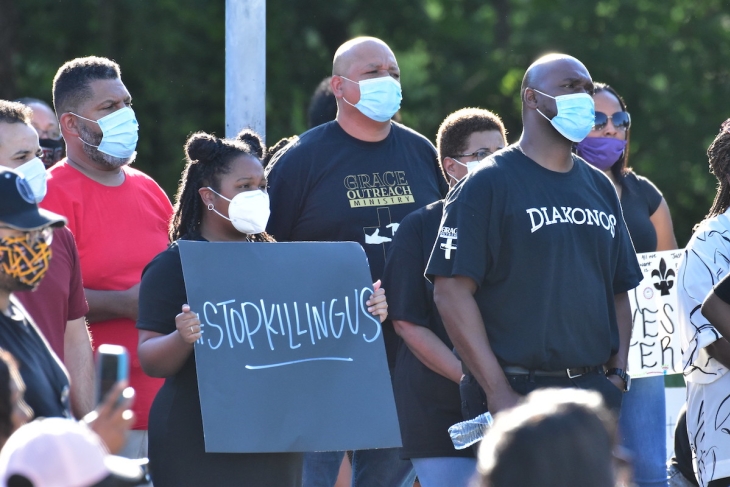

Moments like the early days of the pandemic, when “we’re all in it together” felt like more than an empty slogan, when signs sprouted up and evening applause erupted to thank essential workers—the doctors and nurses, but also the truck drivers and grocery store clerks. And yes, in the aftermath of the awful murder of George Floyd, a black man suffocated to death by an “officer of the peace,” a man whose cries for help went unheeded by four policemen, sickeningly unmoved by his distress.

For maybe a day or two, the nation, consumed with grief and anger, was pulled together by a common understanding that Floyd’s murder was an abomination. That coming on the heels of Amy Cooper, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, and in the context of a COVID-19 crisis ravaging the black community, this was no time to revert to our old arguments about race in America. As Trevor Noah said so eloquently, the dominos are falling. Perhaps this is a chance for something new—especially if the inexcusable violence and looting stops and the peaceful protests continue.

—

Back in our little corner of the world, in the domain of education reform, I’ve been thinking a lot about the culture war. Mostly that’s because of the recent publication of How to Educate an American: The Conservative Vision for Tomorrow’s Schools, which I co-edited with my colleague, friend, and mentor Chester E. Finn, Jr. As the subtitle makes clear, it’s not a book about finding common ground but about clarifying ideological divisions. Here’s how Yuval Levin, the editor-in-chief of National Affairs and the Director of Social, Cultural, and Constitutional Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, explains the rationale in his brilliant chapter:

The era of the reform coalition also exacted some real costs. Above all, it made American education policy awfully clinical and technocratic, at times blinding some of those involved in education debates to the deepest human questions at stake—social, moral, cultural, and political questions that cannot be separated from how we think about teaching and learning. This has meant less of a focus on public schooling as a source of solidarity in American life, which was once a powerful theme on the left in particular. And it has meant less of an emphasis on character formation and civic education, which were once fundamental to the right’s way of thinking about schooling…

Frustrated by the collapse of the reform coalition but also liberated from its constraints, the right and left will probably take somewhat different directions in education-policy thinking in the coming years. For that reason, it remains useful to consider education policy and politics in terms of left and right. In fact, it may be that the deepest differences between the most intellectually coherent forms of the American left and right actually emerge most clearly around questions of education, and not by coincidence. And for each camp, the concerns that were put aside for the sake of working together in the reform coalition seem likely to be those that now come to the fore.

Alas, Levin is not wrong. Yet I find myself more than a little depressed by the idea of shoring up an agenda for conservatives, even in the principled cause of bringing “viewpoint diversity” to our issue, as Princeton professor Robby George puts it in his essay.

Truth to tell, I liked the bipartisan age of welfare reform, balanced budgets, and No Child Left Behind—especially since poor kids and kids of color made so much progress at that time. I am much more comfortable fighting the good fight for charter schools and testing and accountability than slugging it out in the culture wars per se.

Still, given the political leanings of most teachers, administrators, and education officials, if conservatives don’t engage in debates about how to handle these issues right, we will cede our public schools to the left just as we have ceded our elite universities to the left. That’s akin to ceding our nation’s future as well.

So it’s essential for conservatives to offer answers to cultural questions. Eliot Cohen, Dean of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, advocates an approach to teaching American history that is both “patriotic” and “critical"—a sharp distinction from the approach of Howard Zinn or the 1619 Project. Peter Wehner, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center (EPPC) and contributor to The Atlantic and The New York Times, calls for a renewal of character education, one that is not afraid of “inculcating virtue in the young through moral precept, through example and habit, through rewards and punishment, through conversations and stories.” Mona Charen, a syndicated columnist and also a senior fellow at EPPC, urges schools to teach teenagers that their decisions around parenting and marriage will have at least as much consequence for their lives as whether they choose to go to college.

The goal of these arguments isn’t so much to envision a school system imbued with conservative values, but instead to help pull our public schools back to the center.

Which brings me back to today’s crisis.

—

While Joe Biden continues to be a gaffe-machine, including on the sensitive issue of race, America’s schools could learn a lot from his speech about how to handle two hot-button issues: the teaching of American history, and the development of “social and emotional” skills, or what we conservatives more comfortably call “character.” He carved a middle path between right and left that is anything but the mushy middle (despite what the Wall Street Journal might say).

First, history. As several of us discussed at an AEI event last week, nobody should want a Blue American History for kids in Blue America, and a Red American History for kids in Red America. We should all strive for a Purple History, one that doesn’t whitewash the many times our nation has failed to live up to its ideals, especially with respect to the treatment of African Americans, but also doesn’t leave out the many inspiring times that it did. Biden shows how it’s done:

The history of this nation teaches us that it’s in some of our darkest moments of despair that we’ve made some of our greatest progress.

The Thirteenth and Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments followed the Civil War. The greatest economy in the history of the world grew out of the Great Depression. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 came in the tracks of Bull Connor’s vicious dogs.

And:

It’s been reported that on the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated, little Yolanda King came home from school in Atlanta and jumped in her father’s arms.

“Oh, Daddy,” she said, “now we will never get our freedom.”

Her daddy was reassuring, strong, and brave.

“Now don’t you worry, baby,” said Martin Luther King, Jr. “It’s going to be all right.”

Amid violence and fear, Dr. King persevered.

He was driven by his dream of a nation where “justice runs down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Then, in 1968, hate would cut him down in Memphis.

A few days before Dr. King was murdered, he gave a final Sunday sermon in Washington.

He told us that though the arc of a moral universe is long, it bends toward justice.

And we know we can bend it—because we have. We have to believe that still. That is our purpose. It’s been our purpose from the beginning.

To become the nation where all men and women are not only created equal—but treated equally.

To become the nation defined—in Dr. King’s words—not only by the absence of tension, but by the presence of justice.

And:

American history isn’t a fairytale with a guaranteed happy ending.

The battle for the soul of this nation has been a constant push-and-pull for more than 240 years.

A tug of war between the American ideal that we are all created equal and the harsh reality that racism has long torn us apart. The honest truth is both elements are part of the American character.

At our best, the American ideal wins out.

It’s never a rout. It’s always a fight. And the battle is never finally won.

So, too, when it comes to the mission of schools beyond the academic, vocational, and civic. In the Venn diagram displaying the overlap between “SEL” and “character education,” surely there is space for empathy, one of the loftiest of virtues, particularly essential at a time like this. And Biden models it beautifully:

I know so many Americans are suffering. Suffering the loss of a loved one. Suffering economic hardships. Suffering under the weight of generation after generation after generation of hurt inflicted on people of color—and on black and Native communities in particular.

I know what it means to grieve. My losses are not the same as the losses felt by so many. But I know what it is to feel like you cannot go on.

I know what it means to have a black hole of grief sucking at your chest.

Just a few days ago marked the fifth anniversary of my son Beau’s passing from cancer. There are still moments when the pain is so great it feels no different from the day he died. But I also know that the best way to bear loss and pain is to turn all that anger and anguish to purpose.

All of this gives me hope. If someone running for president can find a way to reach out to black and white, to left, right, and center, and can address our history, our values, and our complicated relationship with race in a way that promotes unity rather than division, so can our schools. And maybe that will help our moments of common cause, of civic friendship, last more than a day or two at a time.