Some Democrats and Republicans have an unlikely alliance these days around one thing: their sudden rejection of the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP), which funds start-up costs for new, high-quality charter schools.

President Trump, who says he supports charter schools, surprised charter advocates back in February when his administration’s FY 2021 budget proposal collapsed the CSP into a K–12 block grant, which, if enacted by Congress, would effectively eliminate the program. Democrats, too, have suggested getting rid of the CSP. And while Democratic nominee Joe Biden hasn’t taken a stance on the CSP specifically, the Democratic platform promises to “increase accountability” for charter schools.

Calls to eliminate the CSP go against both parties’ long-standing support for the program, which the Clinton administration enacted in 1994. The Bush administration helped launch two of CSP’s subprograms—Credit Enhancement and the State Charter School Facilities Incentive Grant (SFIG)—and oversaw consistent increases in funding for the CSP. The Obama administration oversaw the highest annual percent increase in appropriations to the program since Clinton. Under the Trump administration, funding reached its current high of $440 million, though, as noted above, its most recent budget proposal would effectively zero it out, given that states could choose to spend any block grant dollars on a wide range of activities instead of starting charters.

Not only do both sides’ current arguments overlook long-standing bipartisan support, they also ignore the long history of charter schools serving some of the nation’s highest-need students and communities. In the midst of health and economic crises that disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic communities, cutting federal funding that supports schools serving those very populations is simply unconscionable.

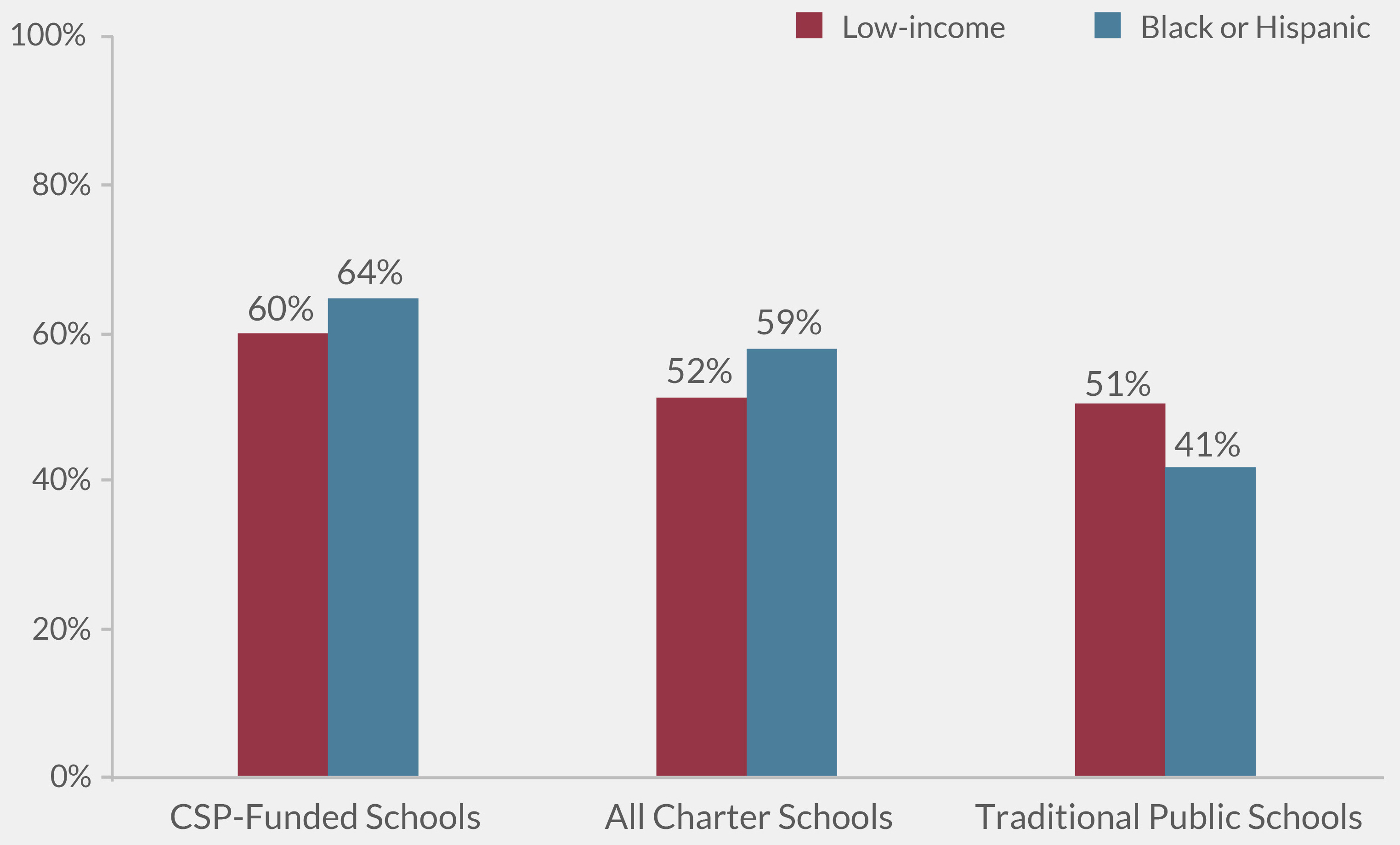

The charter school sector serves higher rates of low-income and Black and Hispanic students compared to traditional district schools. Charter schools that are recipients of federal CSP grants serve even higher rates of low-income and Black and Hispanic students: fully 60 percent of students in CSP grantee schools are from low-income backgrounds, and 64 percent are Black or Hispanic.

Figure 1. Percentage of study population that is low-income and Black and Hispanic, by school type

Source: Data for CSP-funded and traditional public schools obtained from the U.S. Department of Education and NCES CCD.

Without the start-up funding provided by the CSP, many of these schools simply would not exist: Just nineteen states and D.C. provide start-up or planning grants to new charter schools, and those that do provide far less than a charter school typically needs. And philanthropic dollars, while critical for some charter schools, are unevenly distributed across the sector. Just one-third of all charter schools receive 95 percent of all philanthropic support, while 34 percent of charter schools receive no philanthropic support at all. It’s more than likely that these already-limited sources of start-up funding will become even more constrained as the current health and economic crises wear on.

In a new report released last week, my colleagues and I offer a non-partisan look at the CSP to better situate the debate in its true context, looking deep into the history of the program, its current design, and some common critiques. Consider this a Congressional Research Service–type report for those who want the facts about what the program is, how it works, and how it could be improved.

To be sure, the CSP isn’t perfect. For example, although “supporting innovation” is one of the goals outlined in the legislation, and innovation is a core component of the charter school theory of action, Congress and the U.S. Department of Education (USED) have struggled to assert innovation as a central goal of the CSP. As a result, not all elements of the CSP’s subprograms are designed to encourage innovation or tolerate appropriate levels of risk. This makes it too easy for stakeholders to misinterpret charter school closures as a waste, rather than as an investment in the process of innovation that the sector overall can learn from.

There’s also more that can be done to strengthen the CSP’s data collection processes to ensure that Congress and USED have the information they need to rigorously evaluate the success or failure of the CSP overall or its individual subprograms—and, just as importantly—aren’t collecting a slew of data they don’t need.

But while some Democratic and Republican lawmakers would have us throw the program out altogether, we offer a set of recommendations for how to strengthen the CSP so that it can continue to support high-quality schools for high-need students:

- Support charter schools’ access to facilities by increasing the annual appropriation to the Credit Enhancement and SFIG programs and by addressing key challenges in these programs that will enable them to support more schools.

- Support schools that serve high-need student populations by retaining the CSP’s current focus on low-income students and other underserved groups, including those in rural communities and Native American students, and by finding new ways to prioritize other high-need groups of students, such as those with disabilities or those who are experiencing homelessness or are in foster care.

- Find new ways to address barriers to equitable access, especially enrollment processes and transportation.

- Assert and protecting innovation as a central goal of the CSP by articulating the role that innovation plays in developing a high-quality charter sector and ensuring that the design of CSP subprograms supports that goal.

- Better measure, capture, and communicate the CSP’s impact by articulating a clear vision for the CSP overall and aligning data collection and analysis processes to that vision.

It’s more important than ever to shore up resources for schools, especially those that serve high-need communities disproportionately affected by Covid-19. Preserving and strengthening the federal CSP must be a core component of that effort.

Kelly Robson, Ed.D, is an Associate Partner at Bellwether Education Partners.