Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2021 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can schools best address students’ mental health needs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging academic instruction?” Click here to learn more.

This year’s Wonkathon prompt has the right energy, but asks the wrong question.

While academic outcomes matter, ed reformers and policy wonks too often overemphasize their importance. Although we don’t have a set position on this (or anything else) at Bellwether, I believe the evidence suggests school and district leaders should prioritize students’ holistic well-being and quality of life over their academic performance. Notwithstanding a global health crisis, research demonstrates that healthy students have better academic outcomes. So after more than a year of collective trauma brought on by Covid-19, a better question is: “How can schools best prioritize student health and well-being coming out of the pandemic, leveraging federal and community resources to equitably support students and families on their healing journeys?”

This is more than semantics. How we define a problem impacts how we solve it, or if we solve it at all.

To provide support to students, we must first broadly reframe “mental health needs’’ as facets of overall well-being. As a health psychologist and education researcher, “mental health” is a phrase I often see educators and ed reformers overuse without unpacking. School leaders and teachers talk about social and emotional learning and students’ mental health needs without fully understanding the interconnectivity of all aspects of well-being. The mental health concerns that schools seek to help students cope with—anxiety, depression, grief, trauma, and suicidality—have physiological components, including fatigue, changes in appetite, and racing heartbeat. Emotions are embodied processes, grounded in, and happening to, bodies every day.

There is universal agreement that factors outside of academics impact student learning, including how well students and teachers are supported. However, the field has generally been slow to build the infrastructure needed to truly support student health in holistic ways. Below are three policy and practice approaches schools and districts can take to begin cultivating a culture of holistic health advocacy in schools to better support students and families as they work to heal.

1. Adopt a holistic wellness framework to fully understand and address student well-being

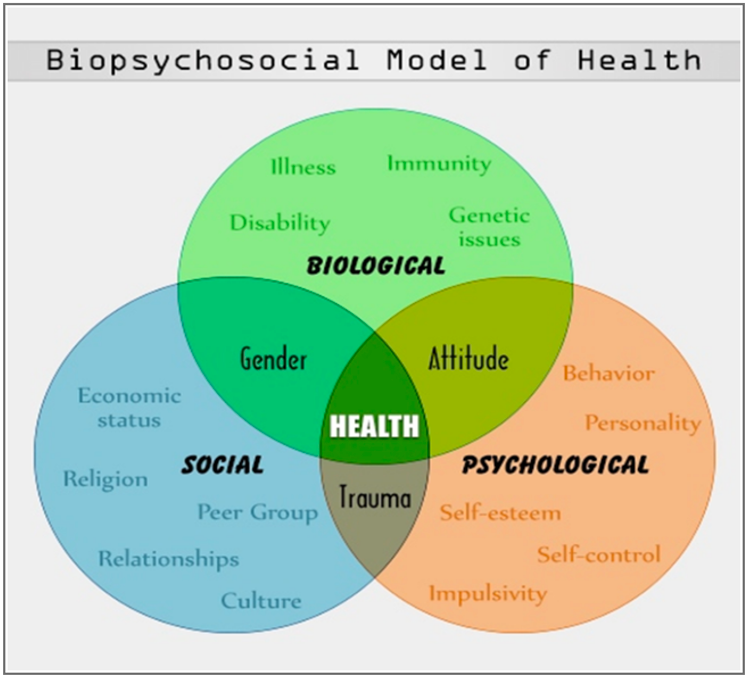

Mental and physical health are inextricably linked. Efforts to prevent illness and promote wellness often need to take many factors and social determinants of health into account, including neighborhood environment, racism, and access to education. Schools and districts should adopt a holistic wellness framework such as the biopsychosocial ecological model, which takes a systems-level approach to collectively consider biological, psychological, and social factors and their complex interactions in understanding health, illness, and health care delivery.

Source: Hart, 2018. Safety & Health Practitioner Online.

What do biopsychosocial models look like in practice? School-based health care approaches exemplify these models, as they are grounded in a focus on developing partnerships, frameworks, and policies that provide students with greater access to holistic care to thrive in and outside of the classroom. The many benefits of this approach include enabling school leaders to name, measure, and address all factors that potentially affect students’ well-being and academic outcomes, and tailor supports and interventions to meet students’ and families’ needs.

Biopsychosocial approaches also help situate access to a high-quality education as a human right and a health equity issue. Drawing on holistic wellness models pave the way for a systems-level approach to student well-being—one that contextualizes the work of improving student outcomes with the knowledge that the educational inequities educators are diligently working to address impact bodies in visceral ways.

2. Gauge community needs to develop a clear understanding of where to direct resources

To develop a culture of health advocacy, schools and districts must engage key stakeholders and partners. As pandemic recovery efforts roll out, equitable, data-driven processes should support the holistic aspects of student well-being to uncover gaps in care.

Community health and mental health data are often available at the state and county level through departments of health. The County Health Rankings & Roadmap tool can help localities determine the most pressing well-being and quality-of-life issues that their communities face. The KIDS COUNT Data Center also provides information that schools and districts can use to better understand local youth health and mental health needs.

Educators should view schools as unique health care settings; attempts to gauge student and family well-being must consider schools’ impact on health outcomes. Truly inclusive approaches should solicit student and family input on the role schools play in supporting or detracting from their well-being—through factors such as general stress, exposure to racism, and/or poor school building conditions—and embed it in broader data-driven family engagement strategies.

3. Equitably distribute funding and resources to support those hardest hit by the pandemic

Once schools and districts have thought critically about their framework for understanding student well-being and gauged community needs, they must equitably allocate funds and resources to marginalized communities. Schools and districts have historically struggled with this; recent research shows that 45 percent of school districts across forty states do not allocate more funding to higher poverty schools.

The Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan Act allows schools to use its ample funds to ensure provision of mental health care and pay for equipment, repairs, and training to foster safe school spaces. To ensure equity, schools and districts should allocate more funds to historically underserved communities, including school facility investments in under-resourced neighborhoods to create clean, safe, and healthy learning environments. Schools and districts should also use funds to hire more mental health professionals of color to better support students who have disproportionately experienced racial trauma throughout the pandemic, and to prioritize the provision of wraparound supports in areas with limited access to high-quality health and mental health care services.

Finally, schools and districts can use funds to leverage existing community resources that provide targeted supports for specific student populations. Schools and districts can foster community partnerships with organizations that specialize in supporting the health and mental health needs of communities of color, people who identify as LGBTQ, and people from low-income backgrounds to develop educator capacity in culturally sustainable and trauma-sensitive practices. There is also an opportunity for schools and districts to allocate funding to incentivize cross-agency partnerships focused on improving student well-being to improve multiagency coordination in areas that predominantly serve students with multiple marginalized identities.

Prioritizing students’ well-being is not counter to improving students’ academic outcomes, and will actually help in that respect. Similarly, students’ mental health needs are important to consider coming out of the pandemic, but they do not exist in a vacuum. As schools and districts move forward, adopting a holistic approach to understanding student well-being, engaging stakeholders, and building plans to equitably distribute resources can better address the multifaceted needs of students and families to ensure improvements in education and health outcomes alike.