It is becoming increasingly clear that pundits and well-meaning education advocates fail to fully grasp the deep distrust that some parents have long had for their children’s schools. A steady stream of articles, op-eds, and twitter threads tell us that closed schools are doing the most damage to children of color, children from low-income families, and children with special needs. Yet many parents of the children who fall into one or more of those categories do not want their schools to reopen—and say that, if they do reopen, they will not send them. This is a major head scratcher for people who have never been zoned to an unsafe or chronically underperforming school.

There is a profound lack of understanding between parents who have only known chronically underperforming schools and parent advocates who have never had that experience but are very familiar with academic data and how it breaks down by race and income.

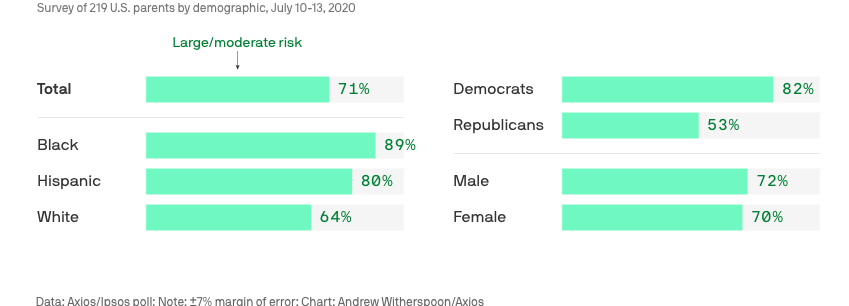

I have been fielding questions since the summer from people who see the consistent survey and polling results and can’t understand why black parents and low-income parents are the least likely to want their children to return to school in person. Or why Latino parents seem much more hesitant than White and Asian parents. The questions are coming from a good place, from people who know the data around reading proficiency and academic outcomes and are convinced that the children with the greatest needs are the ones who most need to be back in school. To their mind’s eye, this is obvious. And it’s easy to see why.

But there is a blind spot in this question that comes from lack of personal experience with really bad schools. Sarah Carpenter is a mother and grandmother in Memphis, Tennessee, who has been fighting for quality education for her own family and countless others for decades. In her current work as the Executive Director of The Memphis Lift, she knows the pain of that broken trust all too well. I spoke to her on a day she had three school-aged grandchildren and one great grandchild with her. The school aged ones have formed a pod to do their distance learning at Grandma’s house.

Carpenter does not pull any punches when she talks about schools reopening. Having seen her own daughter and other family members get sick with Covid-19, the fear is real and personal. She uses the word “terrified” to describe how she feels when she imagines her grandchildren bringing the virus home to her from school. She has diabetes.

I hope you receive this in the manner it is intended, in-person v. virtual school Twitter does not represent parents who are terrified to send their children to school during a pandemic. No matter what the science says, parents know what they know about what can be trusted.

— Vesia (@VesiaHawkins) December 8, 2020

I think the concern among Black and Brown parents in my district is this: if the district can’t implement proven strategies to protect 80% of their children from illiteracy, how confident should we be that they’ll protect those same students from Covid?

— Jim (@jim_again) December 8, 2020

Figure 1: How much of a risk to your health and well-being is sending your child to school in the fall?

Many will be quick to jump on those fears and share studies that show that Covid-19 is not spreading in schools. But this is where the fundamental issue of distrust comes into play. There have already been rumors of cases in their schools, and because of past experience with dishonesty and lack of transparency by school officials, she and others in the community don’t know who or what to believe. As my colleague Mike Petrilli wrote last year, “reopening decisions are mostly a matter of trust.”

“It makes me upset when people act like they’ve got this down pat when they don’t,” Carpenter said. She added that she and other parents in her North Memphis community knew their kids were behind academically long before the pandemic. She wonders why anyone thinks they would jump at the chance to get their kids (and grandkids) back into schools that plan to keep on doing what they were doing before. She says there has been no indication that anything will be different in the schools, other than fears of a virus they see ravaging their community.

Joe Cantu, a father of two in San Antonio and the co-founder of MindshiftED, echoes Carpenter. His son Lucas is ten years old and has Type 1 Diabetes. If he couldn’t trust the school before a pandemic to be sure his son got his shots, how can he be sure that they’re going to keep him safe now when he’s in a high-risk category for the virus?

“I admit I’ve had trust issues with the school,” he says. He points out that parents left in March with no idea how their kids were doing academically and, like Carpenter in Memphis, wonders why anyone would rush back to a place that wasn’t even transparent with us about the most basic information about our children. “If a child is in eighth grade and reading on a second-grade level, why don’t we know that?” he asks.

He goes on to express frustration that the conversation is so focused on getting students back into buildings. “It drives me bonkers that no one seems to be talking about making remote learning as good as possible,” he said. He contends that if families had a really good and “robust” option that allowed them to keep their kids home forever, they would. As far as he is concerned, more than half the children in his city already don’t read on grade level, and he sees little sense in the idea that the only way to get kids caught up is to send them back into the same classrooms they left in March.

Cantu also hits on the transparency issue: “Transparency and accountability were not strengths before. Now I’m supposed to believe they will be? If you’re hiding information about how kids are doing, how can I be sure you won’t be hiding information during a pandemic?”

It is inevitable that readers familiar with “the science” will be tempted to immediately start sharing links to studies from Europe or pieces by Brown professor Emily Oster about the low risk of catching Covid-19 at school. And that makes perfect sense because they are not looking at the pandemic through a prism of decades of distrust and educational failure. What may look like ignorance or an anti-science mindset to the highly educated, including physicians and scientists, is the actual life experience of the parents and caregivers for whom they advocate. Failure to understand and address these very real fears of parents will be a disastrous mistake with long term consequences.

Trust is a necessary ingredient for schools to thrive. Experts, advocates, and school officials would be wise to listen to understand before rolling out data dashboards and sharing quotes from Dr. Fauci that fail to land with the parents they are trying to persuade.

Editor’s note: This was first published on the author’s website, Project Forever Free.