Teachers are the most important in-school factor driving student achievement, and how schools compensate them matters immensely. Entry-level teacher pay is particularly important, as it affects recruitment efforts. Starting salaries influence high school and college students’ decision to pursue teaching (or not), as well as early- or mid-career professionals considering a jump into the classroom. More locally, what individual school districts pay first-year teachers impacts their ability to compete for talent with other districts. Lower starting pay will make a district less attractive to job-seekers and vice versa. High-poverty districts and schools, where working conditions tend to be tougher, need to offer higher salaries to attract talented individuals to their campus.

Conventional wisdom holds that starting teacher pay is mediocre and remains a significant barrier to developing a high-quality workforce. This perception may reflect gloomy media coverage—often influenced by the unions—that casts teachers in general as underpaid and overworked, despite evidence that the teacher “pay gap” is more myth than reality. More specific to starting salaries, state policy may also add fuel to the low-pay narrative. Under Ohio law, districts must pay a minimum first-year teacher salary of just $35,000. This amount—akin to a minimum wage—is routinely discussed by state legislators and featured in news articles, and could easily be understood as the starting salary that districts actually pay.

But what do first-year teachers in Ohio earn? Are their salaries as meager as they are often portrayed? What about high-poverty districts: Are they more prone to paying low starting salaries?

There is no system-wide reporting on districts’ starting teacher salaries. Average salaries are readily available, but first-year-only salaries are not. To locate this information, Fordham intern Heena Kuwayama and I dug up the salary schedules of school districts in Franklin and Cuyahoga counties, the two largest in Ohio. These schedules disclose the salaries that a district’s teachers make based on their years of experience and college degrees/credits-earned, and are included in collective bargaining agreements posted by the State Employment Relations Board. We focus on salaries for first-year teachers with a bachelor’s degree as their highest credential.

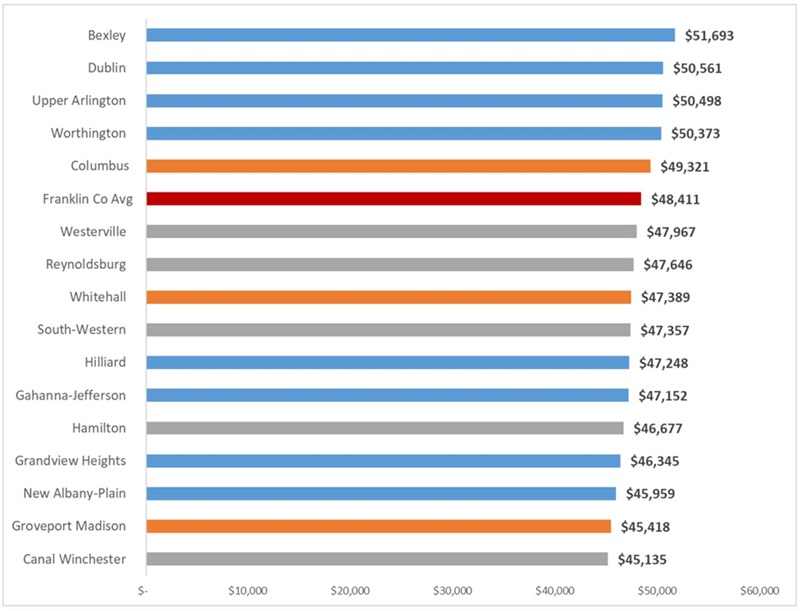

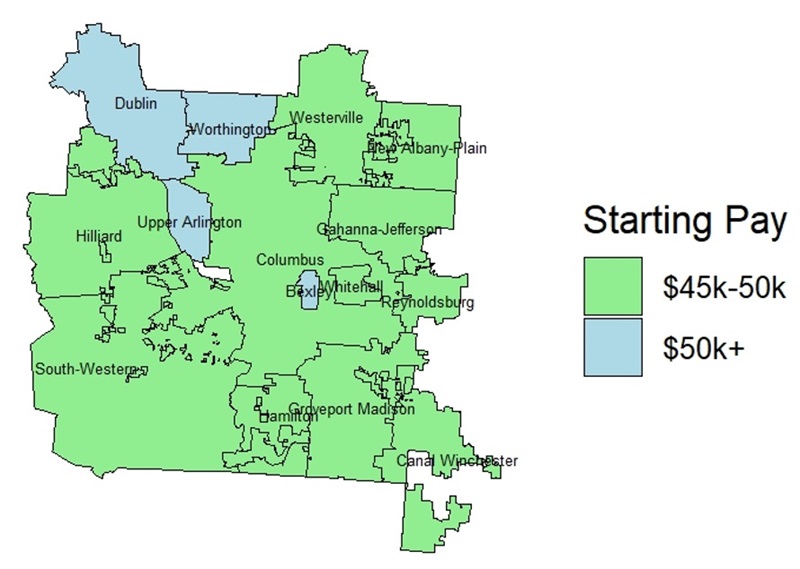

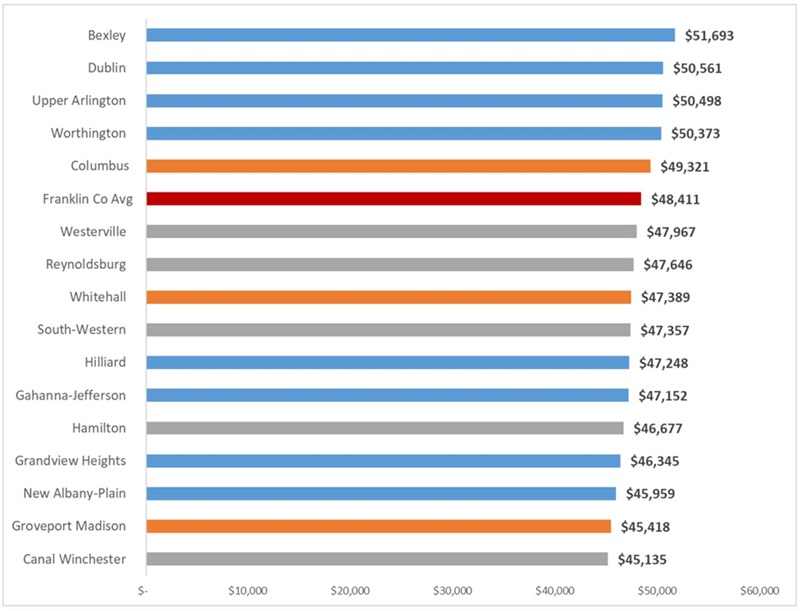

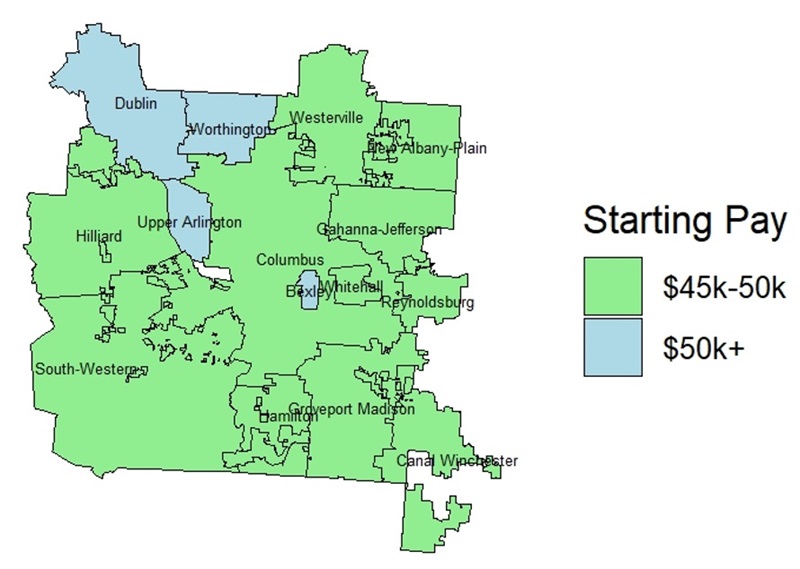

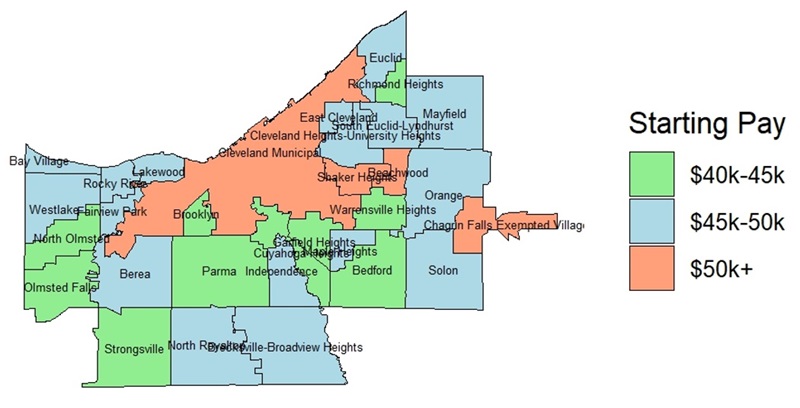

We begin in Franklin County, which includes Columbus and its suburbs. The figure below shows that the average starting salary in the county is $48,411—a healthy 38 percent above the minimum starting pay required in statute. Franklin County districts’ starting pay falls within a relatively narrow range of roughly $45,000 to $50,000, with Columbus paying a reasonably competitive wage that is slightly above the county average and about 10 percent higher than wealthy districts such as Grandview Heights and New Albany-Plain, though below other wealthy districts, including Bexley and Dublin. The maps below, created by my Fordham colleague Adam Tyner, show where the highest-paying school districts are located in the county.

Figure 1: Starting teacher salaries (BA) in Franklin County school districts (FY 2024)

Note: Districts are color coded by their percentage of economically disadvantaged students: Blue = 0–33%; Gray = 33–66%; Orange = 66–100% economically disadvantaged.

Note: Districts are color coded by their percentage of economically disadvantaged students: Blue = 0–33%; Gray = 33–66%; Orange = 66–100% economically disadvantaged.

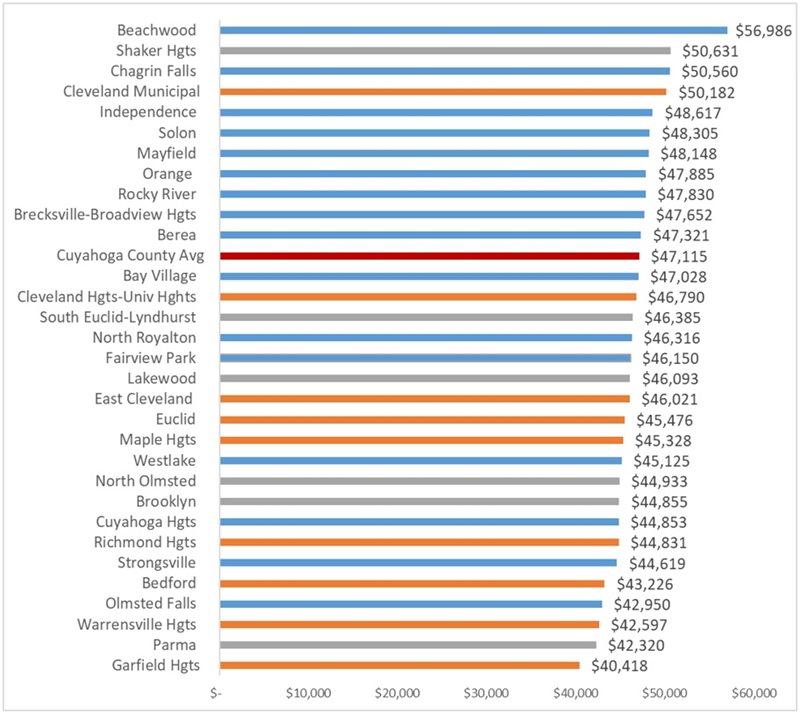

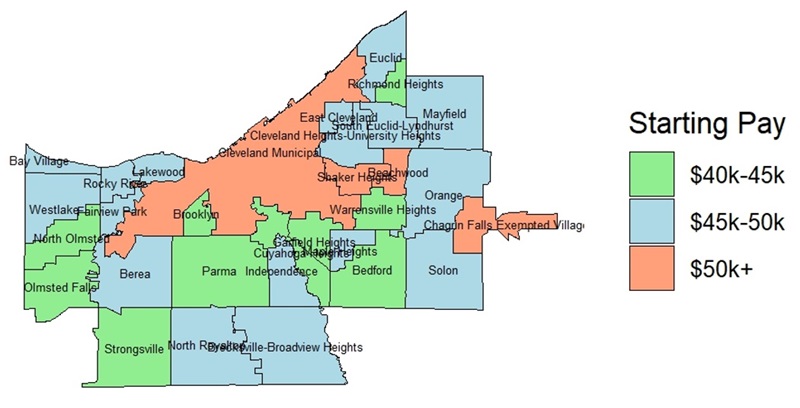

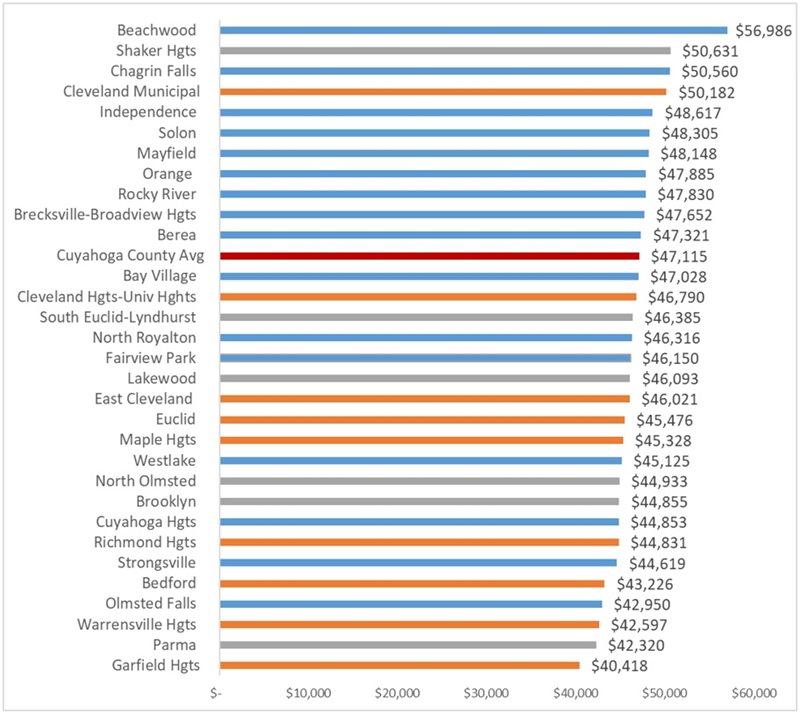

Turning to Cuyahoga County (Cleveland and its suburbs), we notice that districts tend to pay slightly lower starting salaries than Franklin County. Here, average starting teacher pay is $47,115, or 35 percent above the state minimum of $35,000. There is somewhat more variation in starting salaries across Cuyahoga County districts, as pay ranges from approximately $40,000 to $50,000. And we also see a stronger link between districts’ starting salaries and economically disadvantaged rates. Eight of the ten highest-paying districts are wealthy, while the lower-paying districts tend to be mid- and high-poverty. That said, Cleveland boasts one of the highest starting salaries in county at just above $50,000.

Figure 2: Starting teacher salaries (BA) in Cuyahoga County school districts (FY 2024)

As noted earlier, higher-poverty districts likely need to offer more generous starting salaries to attract top-notch teachers. But do they have the funding necessary to do so?

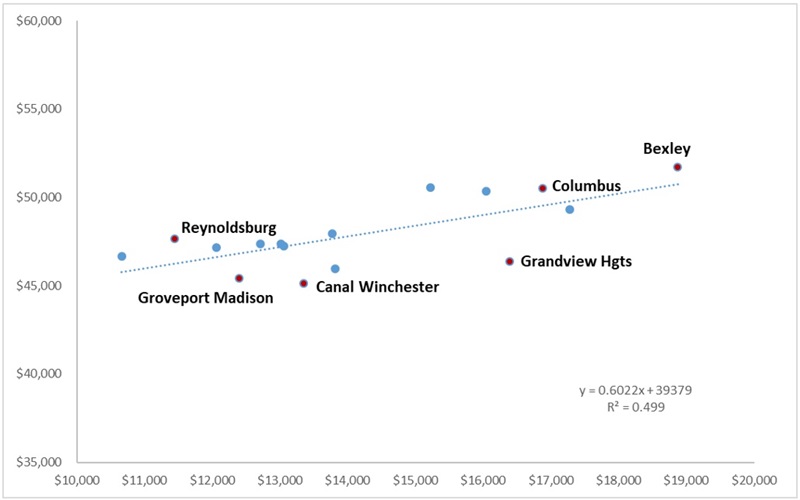

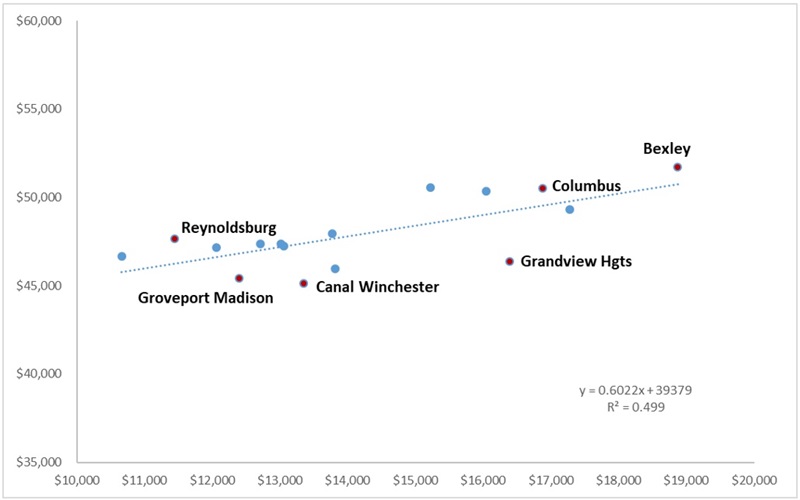

To explore this, Figure 3 looks at the correlation between per-pupil funding and starting pay in Franklin County. We see that mid-poverty districts such as Canal Winchester, Groveport Madison, and Reynoldsburg pay slightly lower entry-level wages, perhaps because they are more budget constrained (receiving less funding to begin with). But it’s not an especially strong correlation, as Reynoldsburg, for example, provides higher starting salaries than Groveport Madison, which receives more funding. Columbus receives relatively high levels of funding and pays better starting salaries than most Franklin County districts.

Figure 3: Total revenue (state and local, FY23) versus starting teacher pay, Franklin County districts

Note: This chart displays each district’s total state and local revenue per pupil (FY23) on the x-axis and its starting teacher salary (y-axis). Federal revenues are excluded as the uses of these funds are more restricted, and would also include significant sums related to the Covid-relief effort that were not directly intended for teacher salaries.

Note: This chart displays each district’s total state and local revenue per pupil (FY23) on the x-axis and its starting teacher salary (y-axis). Federal revenues are excluded as the uses of these funds are more restricted, and would also include significant sums related to the Covid-relief effort that were not directly intended for teacher salaries.

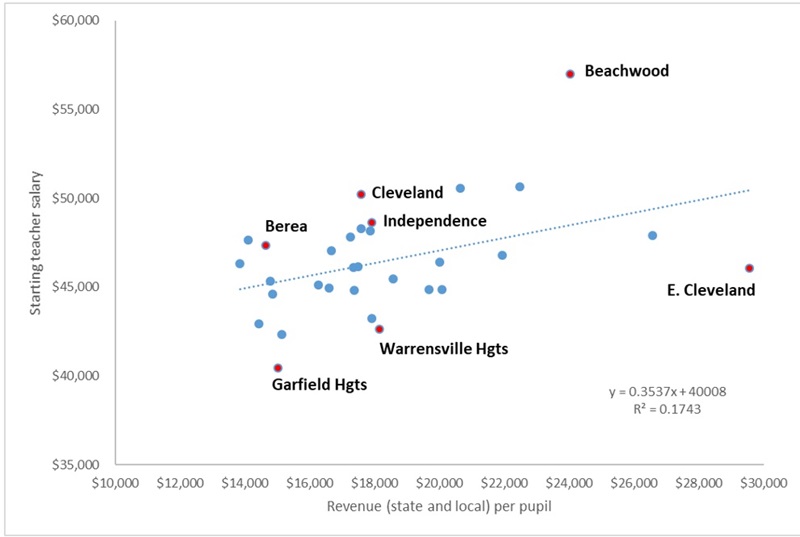

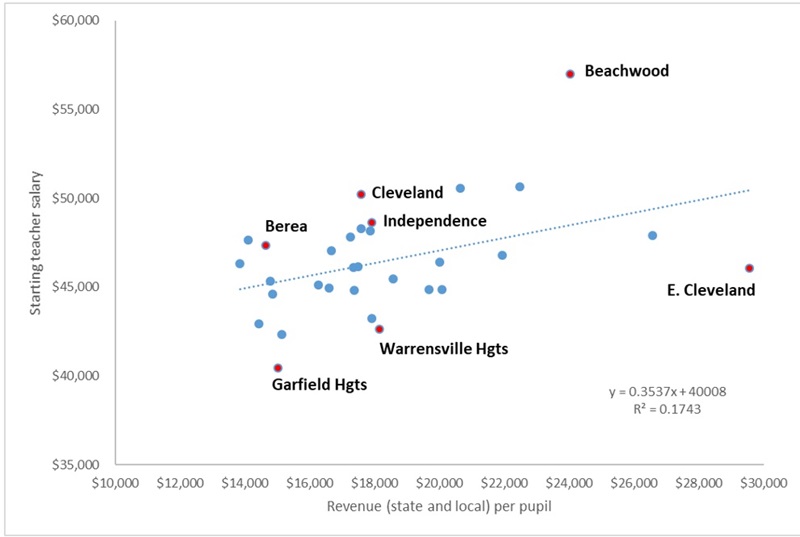

Figure 4 reveals a weaker correlation between Cuyahoga County districts’ revenues and starting teacher pay. Here, the lowest-paying districts in the county often receive comparable funding to districts that provide more generous starting pay. Garfield Heights, for example, pays first-year teachers $40,418, but similarly-funded Berea pays $47,321. Warrensville Heights’s starting salary is $42,597, yet similarly-funded Independence pays $6,000 more to first-year teachers, while Cleveland pays about $8,000 more. East Cleveland is the highest-funded district in the county, spending almost $30,000 per pupil, yet manages to pay new teachers just $46,021 a year. Taken together, these data suggest that funding levels are not the primary barrier to higher starting salaries, but more so a low prioritization of entry-level salaries in the district budget.

Figure 4: Total revenue (state and local, FY23) versus starting teacher pay, Cuyahoga County districts

* * *

Three concluding thoughts on these data:

1. Starting teacher pay is reasonably good in Ohio’s largest metro areas—and that should be more widely known. Most first-year teachers in the Columbus and Cleveland areas are paid $45,000 to $50,000 per year (not including benefits). That’s not half bad, especially for twenty-two-year-olds in their first professional jobs. Of course, these salaries aren’t as large as what some students make out of college, including those who enter more lucrative STEM fields. But starting teacher pay is not that far off from the median statewide salary for all Ohio working adults of about $60,000. And it’s far superior to what a large portion of college students earn early in their careers (one study this year found that a quarter of graduates earn less than $32,000).

Making actual starting salaries better known might persuade more young people to consider teaching. Remember also that, even in its largest cities, Ohio remains a relatively affordable place to live and work, allowing these salaries to go further than other parts of the country.

2. High-poverty districts have room to improve starting teacher pay, but they need to make it a strategic priority. If lower-salary, higher-poverty districts like Groveport Madison and Garfield Heights seek to more aggressively compete for talent, they need to consider ways to prioritize starting (and early career) teacher pay. One possible strategy is to “compress” the salary schedule—i.e., reduce the number of “steps,” or the incremental pay raises tied to experience—to free-up money to raise entry-level pay. They could also rigorously review spending on administrative and non-teaching staff to make sure that as much funding as possible is dedicated to teacher pay. Finally, while it may require changes in state law, districts should be looking to experiment with more flexible compensation structures that allow for higher pay at the front end of teachers’ careers.

3. State policymakers could make it easier for high-poverty districts to raise starting pay by loosening spending restrictions. Ohio puts restrictions on how districts can spend on a couple pots of state funds: Student Wellness and Success Funding—a specific element within the core “base amount” that districts receive—as well as Disadvantaged Pupil Impact Aid, a categorical “add-on” that drives additional dollars to high-poverty districts. The limits make some sense, but they also compel districts to spend dollars on certain activities and programs—e.g., mental health services, tutoring, and other supports—and not teacher salaries. Lawmakers could relax these constraints and allow districts to use these funds to raise teacher pay. This could enable high-poverty districts, especially, to boost starting salaries, as they receive more through these elements than their wealthier counterparts.

Entry-level pay is just the beginning. How quickly pay increases is also key in districts’ ability to retain effective teachers. Stay tuned for a follow-up post that looks at how districts compensate their early-career teachers.