Ohio has a lot to be proud of when it comes to the post-pandemic academic recovery—but also much work left to do. That’s the message that comes out of my recent analysis of spring 2024 state assessment data released earlier this month.

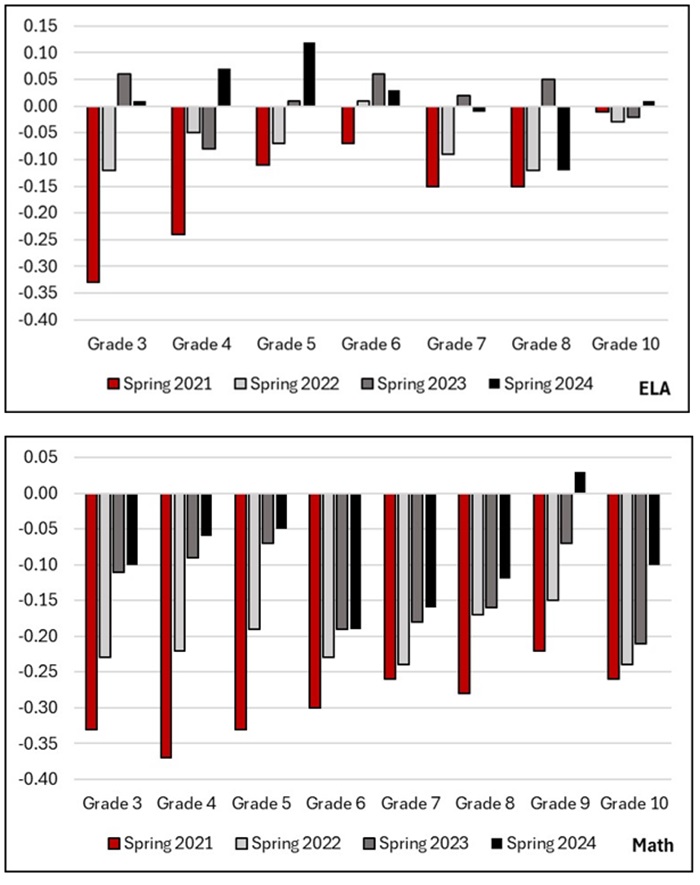

Given our natural inclination to focus on the negative, it is important to start with the good news. In English language arts (ELA), our state has demonstrated tremendous success remediating the learning disruptions we saw emerge in the first year of the pandemic. Indeed, with the exception of eighth graders, Ohio students appear to have completely reversed the large initial achievement declines. And in a number of grades, students performed better last spring than their counterparts before the pandemic. The recovery has been broad-based, benefiting every type of school district and every student subgroup, helping reverse some of the worrying racial- and economically-based achievement gaps we saw grow in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic learning disruptions.

Ohio’s progress on ELA is particularly noteworthy when compared to the broader national landscape. Recently released reports from private assessment companies have painted a bleak picture of stagnation, and on some assessments, students falling further behind. Although it’s not clear why Ohio has bucked this depressing national trend, our state’s concerted focus on improving reading instruction and professional development focused on the latest scientific insights on how students learn how to read may have helped.

Unfortunately, when it comes to math, Ohio’s recovery remains incomplete. Part of this is because the initial achievement declines in math were just much larger, in absolute terms, than in ELA. Even given the same learning gains, it would have taken Ohio students more time to climb back to pre-pandemic levels. And indeed, we did see considerable progress several years ago, with accelerated achievement growth beginning to offset a meaningful share of the pandemic-era losses.

But this progress appears to have stalled out last year, with little evidence of continued math recovery between spring 2023 and 2024 in most grades. As a result, elementary school students remain about a month behind pre-pandemic cohorts in math, with the gap rising to between one-third and one-half of a school year in middle school grades.

Figure 1: Post-pandemic academic recovery by grade in ELA (top) and math (bottom)

The latest numbers point to several important lessons for Ohio policymakers, particularly as they continue to focus on addressing the math achievement shortfall. One is the importance—and limitations—of funding and the other relates to timely data.

On the funding side, the federal government provided school districts across the country more than $200 billion in pandemic-era aid, an unprecedented investment with the stated intent of helping support learning recovery. Ohio schools received more than $6 billion of this funding, and my analyses suggest the money played a role in the partial math rebound: Districts that received more aid, a function of a fixed federal allocation formula, saw their math achievement recover faster in recent years. The magnitude of this effect, however, was fairly modest, with a $1,000 increase in per-student funding raising math achievement by about 0.02 standard deviations. To put that number in context, it would take at least an additional $5,000 for every student in the state to close the remaining math gap at this rate—more than the total amount of federal pandemic aid in Ohio. It seems highly unlikely such a level of investment will be available, especially since the deadline for spending down the remaining federal aid is this year.

Fortunately, the recent improvements in ELA suggests that further progress is possible even in the absence of significant new resources. Unlike in math, where district-level growth depended on the available federal funding, differences in ELA gains across districts were not related to the amount of federal aid that local communities received. The statewide success in addressing the ELA shortfalls show what can be accomplished with sustained focus and attention.

The second lesson is about the importance of timely, accurate data to guide policy. After the cancellation of state tests in spring 2020 at the height of the pandemic, some school employee interest groups saw an opportunity and tried to rally lawmakers to permanently eliminate state testing and accountability linked to it. Wisely, our state leaders resisted these efforts. To the credit of Governor DeWine and top leaders at the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Ohio has been a national leader in working with independent researchers like myself to evaluate state and local recovery efforts and making these results public, even when they didn’t always paint a flattering picture.

This has not been the case in some other states. California, for example, threatened to sue a Stanford researcher whose data portrayed the state’s ham-fisted school reopening and recovery efforts in a negative light. But here in Ohio, we’ve had quality data that have allowed policymakers to clearly understand the magnitude of the academic setbacks, identify school districts and student subgroups most affected, and track progress over time.

Ohio continues to show the country what can be accomplished when we make student achievement a priority. We have made tremendous progress, but it is also clear that the job is not yet complete. It is essential that that academic considerations—as opposed to various education culture wars—remain at the top of our agenda.