As districts across the nation struggle with teacher shortages, policymakers and advocates continue to debate how best to draw more talent into the profession. Increasing salaries inevitably comes up in these discussions, and understandably so, as teachers do a difficult job that’s extremely important. To attract and retain high-quality teachers, districts have to pay wages that allow them to cover the costs of living in their community.

One major cost of living is housing. In a recent analysis, Patricia Saenz-Armstrong of NCTQ points out that there are two issues at play here: the availability of affordable housing and teachers’ ability to afford to rent or buy a home based on their salaries. Short of offering housing to teaching staff—which some districts are doing—there’s not much district leaders can do regarding housing availability. But they play a significant role in determining annual salaries, and therefore teachers’ ability to afford housing. Saenz-Armstrong notes that in the last five years, rentals and average home prices have increased by more than 20 and 40 percent, respectively. Teacher salary increases, however, have not kept pace. As a result, teachers are being priced out of certain labor markets, and that exacerbates already existing teacher shortages. If districts want to attract and retain teachers, they have to pay them enough to live near the schools where they teach.

But just how bad is this problem, and is it a significant issue in Ohio? To determine where teachers are the most and least likely to be able to afford a home, NCTQ compared the cost of housing in sixty-nine metropolitan areas to teacher salaries in the largest school districts within those locales. Specifically, they sought to shed light on whether beginning teachers can afford to rent a place near the school where they teach; how long it takes a teacher to save up to buy a home; and whether teachers can afford the ongoing costs of home ownership. Let’s take a look at each.

1. Can novice teachers afford rent near their schools?

Examining whether teachers can afford rental prices is crucial, as younger teachers often rent for a few years while they save up to buy a home. In some cities, renting for longer periods of time is the norm, which makes teachers’ ability to afford rent even more important. But for novice teachers with a bachelor’s degree, paying for a one-bedroom rental is unaffordable in fifteen metropolitan areas (without a roommate at least), as the cost adds up to more than 30 percent of their salary. In nine of those fifteen areas, even beginning teachers with a master’s degree—who earn roughly $5,000 more per year on average than their peers—face rent costs that are more than 30 percent of their salary.

The good news is that the metropolitan areas in Ohio that are included in this analysis—Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati, which are home to the state’s three largest school districts—rank among some of the most affordable places for teachers to live in the nation. The NCTQ-created table below identifies the ten most and least affordable districts for an early-career teacher interested in renting a one-bedroom home. All three Ohio districts are among the ten most affordable. In Cleveland and Cincinnati, rent costs just 18 percent of a teacher’s salary, while in Columbus it’s 19 percent.

2. How long will it take teachers to buy a home?

NCTQ notes that it takes a little over four years for the average household to save enough money to make a 20 percent down payment on a home. But for teachers, that wait is much longer. On a single teacher income in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas, it would take 13.6 years to save up 10 percent of their annual income to make a 20 percent down payment on a median-priced house. Teachers with a master’s degree and the accompanying higher salary would need 12.5 years.

As is the case with rental costs, there’s a lot of variation from one place to another. A teacher with a bachelor’s degree working in Kanawha County Schools in West Virginia can buy a home the fastest—it takes just seven years to save for a down payment. Teachers working in Jackson Public Schools in Mississippi, Pittsburgh Public Schools in Pennsylvania, the Detroit Public Schools Community District in Michigan, and the Cleveland Metropolitan School District in Ohio follow at a close second, as they can save for a down payment in eight years. Meanwhile, in San Francisco Unified School District in California, it would take teachers a whopping thirty years to save for a down payment. The Los Angeles Unified School District in California (twenty-nine years), the Hawaii Department of Education (twenty-eight years), San Diego Unified School District in California (twenty-five years), and Portland Public Schools in Oregon (twenty-two years) round out the top five districts where it takes teachers the longest to save up for a down payment.

In Ohio, saving up for a down payment takes far less time than it does out west. According to NCTQ, it would take teachers in Columbus between ten to fifteen years to save for a down payment. Teachers in Cleveland and Cincinnati can do so in less time—just five to ten years.

3. Can teachers afford the ongoing costs of ownership?

To determine the ongoing cost of home ownership, NCTQ turned to the American Community Survey (ACS), which defines that cost as the combined monthly payment for “mortgage principal and interest, real estate taxes, homeowner’s insurance, utilities, mobile home costs, second mortgage payments, and condominium fees if applicable.” Specifically, NCTQ used data from the 2021 five-year ACS for the counties that corresponded with the sixty-nine metropolitan areas included in this analysis. Among the seventy-four districts within these areas, there were forty-nine where the cost of home ownership exceeded 30 percent of a teacher’s gross income (assuming the teacher has a bachelor’s degree and fifteen years of experience). In forty-one of those forty-nine districts, the average cost of home ownership continued to exceed 30 percent of a teacher’s income even after twenty years of experience.

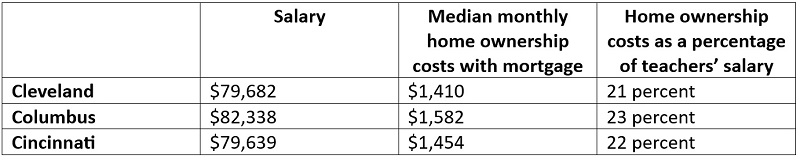

In keeping with the trend, all three Ohio metropolitan areas are much more affordable than most. Although the cost of home ownership adds up to more than 30 percent of a teacher’s gross income in forty-nine other districts nationwide, in the Buckeye State, the three largest districts boast costs that are 23 percent or less.

***

Overall, the data indicate that teachers in Ohio’s big metro areas are better off than many of their nationwide peers when it comes to affording rent, saving up for a down payment, and paying the ongoing costs of home ownership. But that doesn’t mean housing affordability isn’t impacting Ohio’s teacher pipeline. Recently released state data indicate that the main driver of increasing district-level attrition is teacher mobility, rather than teachers leaving the profession or the state.

It’s possible that some of the reason why Ohio teachers are so mobile is because they’re moving to places where housing is more affordable. The three metropolitan areas in this study—Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati—have rents and home ownership costs that are much more affordable than many of the nation’s other big cities. But they’re also Ohio’s largest cities, and the cost of housing in these areas is likely more expensive than it is in some of the state’s suburbs, towns, and rural communities. Ohio might be more affordable compared to other states, but that doesn’t preclude vast differences in housing affordability within state lines.

It's important for policymakers to be aware of how housing affordability can impact the teacher pipeline. NCTQ notes that policies that support low-interest loans and down-payment or housing subsidies for teachers could be effective tools. Ohio’s leaders should also be shouting from the rooftops about how affordable it is to teach and live here compared to other places. But the most important tool for addressing teacher housing issues resides in the toolbox of local schools. It’s imperative for district leaders to offer decent starting salaries and consistent salary increases. If they don’t, it shouldn’t come as a surprise when teachers choose to live—and work—elsewhere.