In just a few short months, Ohio lawmakers will be knee-deep in the state budget for FY 2026 and 2027. A large portion of the budget is K–12 education, and Ohio’s school funding model is sure to be a topic of discussion. This model, named the “Cupp-Patterson plan” after its legislative champions former Speaker Bob Cupp and Representative John Patterson, determines how state dollars are allocated to public schools using a complex formula that takes into account student enrollments and districts’ capacity to raise funds locally.

The Cupp-Patterson plan was heralded as a “fair” and “constitutional” replacement for the state’s previous formula, which was roundly criticized as a “patchwork” and “unpredictable.” The new formula does indeed have strengths, and follows some of the right ideas in crafting school funding policy, including centering the system around where students actually attend school, providing additional resources for less advantaged pupils, and allocating state aid in a “progressive” manner to support schools with less local wealth to tap into. But after four years of implementation, which included a period of sky-high inflation, it’s clear there is still room for improvement. I’ve previously discussed these problematic areas in great detail, but a consolidated inventory, along with some updated analysis, could be helpful as policymakers head into budget season.

So, let’s take a look at three of the six items that should be on their fix-it list (a follow-up piece will cover the rest).

Issue 1: Base-cost model and escalating costs

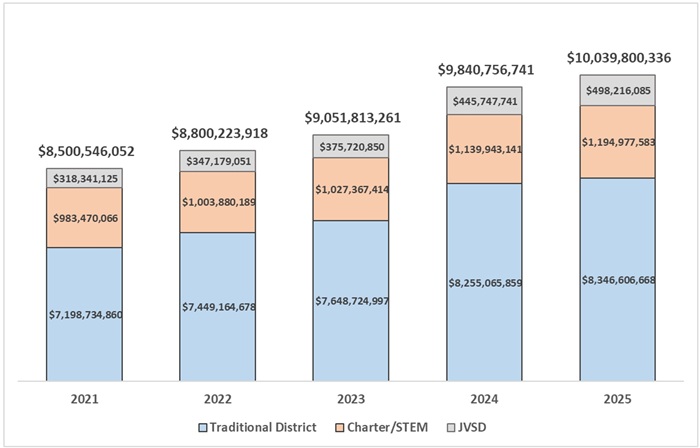

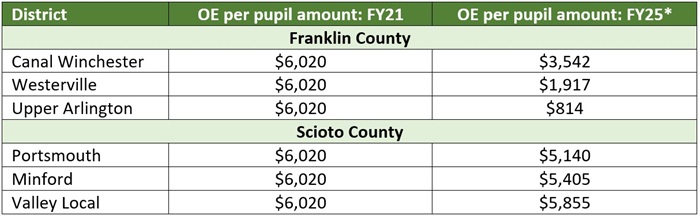

When the Cupp-Patterson plan was first unveiled, the projected cost of full implementation was $2 billion in additional state spending—a roughly 20 percent increase above state K–12 education expenditures at the time. Given the price tag, lawmakers chose to phase in the increase over six years. Thus, public schools have received increased funding over the past four years, though they’re not quite up to the full amounts prescribed by the formula. Even with the phase-in, spending has ramped up quickly under the new formula. Relative to a pre-Cupp-Patterson baseline of $8.5 billion in FY21, Ohio has increased formula funding by $1.5 billion by FY25. All three sectors of the public school system have enjoyed higher funding amounts, with traditional district funding up by $1.1 billion, public charter and STEM schools up by $212 million, and joint-vocational school districts (JVSD) up by $180 million.

Inflation has taken a bite out of these gains, but growth in state formula aid still outpaces inflation over this period. On a per-pupil basis, the nominal increase has been 19 percent from FY21 to FY25, but adjusting for inflation (using CPI), formula funding has risen by a more modest 3 percent. That said, public schools have also received unprecedented federal Covid-relief aid over the last few years, and these numbers don’t include several non-formula funding streams that have pushed additional dollars into Ohio schools (e.g., literacy funding and increased charter supports).

Figure 1: State formula funding, FY21 to FY25

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Statement of Settlement (June payments for FYs 2021–24 and November payment for FY25). Note: These amounts reflect state formula funding and exclude several other state funding programs (e.g., literacy funds in FYs 2024–25 and charter/STEM schools’ equity supplement, high-quality funding, and per-pupil facility aid—elements that are not part of these schools’ permanent formula or the Cupp-Patterson plan). The amounts above do not include local tax revenues, which provided $12.3 billion in FY24 to JVSDs and traditional districts, as well as federal and non-tax revenues that all public schools receive. These amounts do not include state funds for private school scholarships. The numbers are not adjusted for inflation.

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Statement of Settlement (June payments for FYs 2021–24 and November payment for FY25). Note: These amounts reflect state formula funding and exclude several other state funding programs (e.g., literacy funds in FYs 2024–25 and charter/STEM schools’ equity supplement, high-quality funding, and per-pupil facility aid—elements that are not part of these schools’ permanent formula or the Cupp-Patterson plan). The amounts above do not include local tax revenues, which provided $12.3 billion in FY24 to JVSDs and traditional districts, as well as federal and non-tax revenues that all public schools receive. These amounts do not include state funds for private school scholarships. The numbers are not adjusted for inflation.

If the past is prologue, lawmakers are looking at another $500 million to $1 billion increase in the upcoming budget in order to continue implementing Cupp-Patterson. Some of the cost would reflect the final two-year phase-in of the plan, but a bigger factor is whether they choose to update the “inputs” of the formula’s base-cost model. This part of the formula includes detailed calculations that rely on average teacher salaries and other items to generate base per-pupil amounts. In the last budget cycle, this update was quite expensive, as salaries and other expenditures rose significantly (thanks again to inflation) and drove the $1 billion increase from FY23 to FY25. Another update would push the overall cost of Cupp-Patterson upward yet again, likely over the $2 billion mark.

The large expense of implementing Cupp-Patterson—and maintaining it via input updates—has always opened questions about its long-term sustainability. So far, lawmakers have been able to dodge the issue of cost as the state’s coffers have been full in recent years. But boom times end, and lawmakers—whether next year or sometime further down the road—may be less inclined to approve such sizeable increases in a sluggish economy. Other factors could also lead to a budget crunch, including a desire to reduce tax burdens or to increase spending on other programs such as childcare, public sector pensions, and healthcare.

Questions remain: What happens to Cupp-Patterson when there’s a pinch? Will lawmakers resort to imposing much-despised “caps“ to control spending? Will they skip an input update, perhaps punting that decision and its costs to future legislators and thereby throw a wrench into the formula? Would they strip essential formula elements to reduce its cost? Or will they shortchange other government programs to cover the expense?

It won’t be politically popular, but the next General Assembly should explore options that better control the long-term costs of Cupp-Patterson. One option is to reinstate a straightforward base per-pupil amount that is determined biennially by legislators. Another is to tie the base to the statutory minimum salary schedule instead of using average employee salaries, which can inflate quickly when districts pass levies and their local revenues grow. Neither idea implies flat or reduced funding, and lawmakers could always increase funding levels, something they have consistently done in the past. They might even give a nod to Cupp-Patterson by setting the base amount just above the current level and allowing that to rise consistent with the general inflation rate. These types of changes would give the legislature more flexibility to adjust the state’s main education appropriation without being hamstrung by the prescriptiveness of the Cupp-Patterson base-cost model. And as discussed previously and in my follow-up piece, lawmakers should also trim expensive guarantees from the formula, which provide excess funding to districts with declining enrollments.

Issue 2: State-share mechanism and inflation

The formula includes calculations that determine how much of the base amount the state is responsible for funding and how much is assumed to be funded locally (which includes a state-required minimum 2 percent property tax). These computations are based on property values and resident incomes, and yield districts’ state share percentage (SSP). A low-wealth district will have a higher SSP, and in turn receive more state aid, while a high-wealth district will receive fewer state dollars.

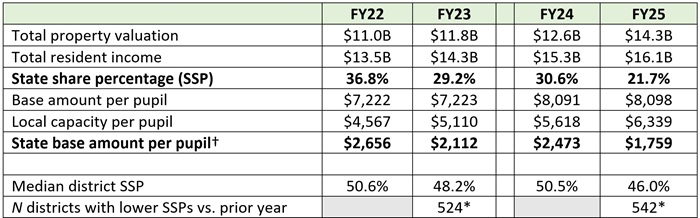

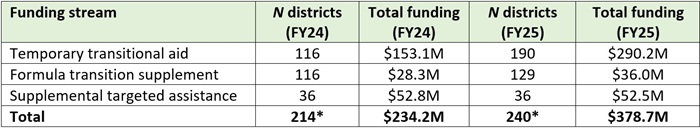

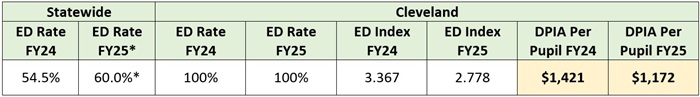

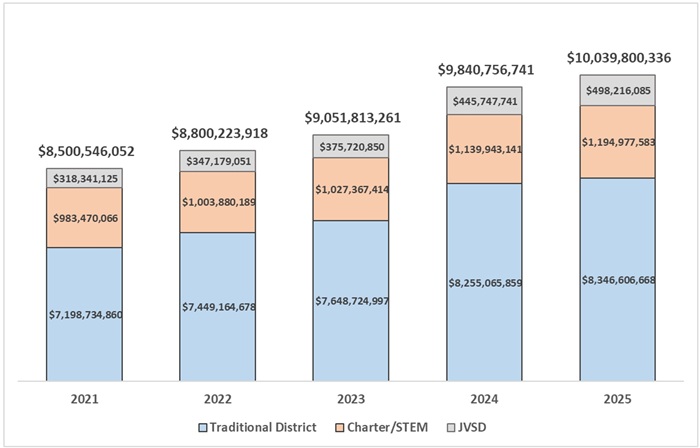

This type of state-share mechanism has long been part of Ohio’s formula and is critical for an equitable system. Yet Cupp-Patterson takes a problematic approach to calculating the measure. The challenge relates to property and income inflation. To illustrate, consider data from Columbus City Schools, whose property values and incomes have risen quite quickly in recent years. From FY22 to FY23, inflation cut the district’s SSP from 37 to 29 percent. In other words, the district suddenly appeared to be much “wealthier”—not necessarily due to greater prosperity, but due to systemic price increase in the city. The lower SSP led to a drop in base state funding of roughly $500 per pupil in just one year ($2,656 to $2,112 per pupil). Updating the inputs during the last state budget cycle boosted the base amount in FY24, which in turn lifted the district’s SSP. But inflation has again eroded the district’s SSP between FY24 and FY25 and reduced its base per-pupil funding by about $700. As the bottom rows of Table 1 indicate, this issue isn’t limited to Columbus. The vast majority of districts have experienced decreases in their SSPs in the second half of the biennium, as inflation takes a toll.

Table 1: Local wealth measures, SSP, and base per-pupil amounts, Columbus City Schools

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Traditional School Districts Payment Reports. Note: (*) Nearly every other district had a flat SSP versus year prior, as they were at the state minimum SSP in both years (5 and 10 percent in FY22–23 and FY24–25, respectively). There are roughly 610 total districts in Ohio. (†) The state base amount per pupil can be computed one of two ways: (1) SSP x base amount or (2) base amount - local capacity. This table also displays the “calculated” amounts assuming full phase in of Cupp-Patterson (not amounts actually received after the application of the phase-in).

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Traditional School Districts Payment Reports. Note: (*) Nearly every other district had a flat SSP versus year prior, as they were at the state minimum SSP in both years (5 and 10 percent in FY22–23 and FY24–25, respectively). There are roughly 610 total districts in Ohio. (†) The state base amount per pupil can be computed one of two ways: (1) SSP x base amount or (2) base amount - local capacity. This table also displays the “calculated” amounts assuming full phase in of Cupp-Patterson (not amounts actually received after the application of the phase-in).

The design of the Cupp-Patterson state-share mechanism puts lawmakers in a dilemma. Absent consistent updates to the inputs, general inflation in local wealth systematically erodes districts’ SSPs over time and reduces state funding. But as noted above, updating inputs has been a costly proposition for the state, even with local wealth inflating at a rapid pace. Overall, Cupp-Patterson is so tightly wound that if one part of the system isn’t functioning (for instance, if input updates aren’t made), then other parts can break (SSPs drop).

How to unravel this is no easy task. One possibility is to revisit the Kasich-era approach to the state-share mechanism, which seemed to better handle inflation by anchoring districts’ state shares to the statewide average. Instead of inflation lowering SSPs systemwide, this “relative” approach to gauging local capacity meant that roughly half of districts had increasing state shares, while the other half experienced decreasing state shares.

Issue 3: Small districts’ excessive base funding amounts

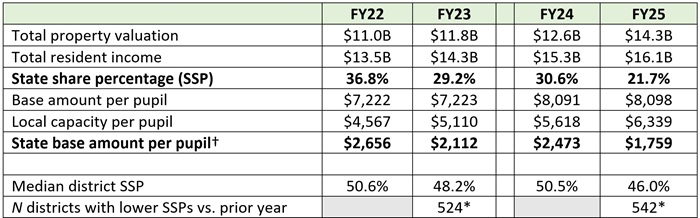

Under the Cupp-Patterson formula, districts receive variable base per-pupil amounts; there is no single number that applies across-the-board statewide. While most districts’ base amounts fall within a narrow band around the statewide average, low-enrollment districts enjoy substantially higher base amounts. This happens because of “staffing minimums” tucked inside the Cupp-Patterson base-cost model. In a vast majority of districts, these minimums don’t apply, and their amounts are determined by simply following prescribed staff-to-student ratios. Small districts, however, have their base amounts computed based on a minimum number of staff, even if their actual ratios yield smaller numbers than the minimums.

Table 2 shows the impact of these minimums on base amounts. The five lowest-enrollment districts have per-pupil amounts that are far higher the statewide average, with tiny Vanlue school district receiving more than twice the statewide average. On average, the 100 lowest-enrollment districts enjoy base amounts that are just over 20 percent above the state average. Does it truly cost that much more to educate a typical student in a low-enrollment district? Cupp-Patterson proponents argued that they incur higher costs because of diseconomies of scale. But at the same time, small districts are mostly located in rural communities where the cost of living is likely far less than metropolitan areas. That should decrease the cost of education or at least offset some of the impact of diseconomies.

Table 2: Small districts’ base funding amounts, FY25

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Traditional School Districts Payment Reports.

Source: Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, Traditional School Districts Payment Reports.

Providing some supplemental aid for sparsely populated districts may be warranted, but this level of extra subsidy—hidden inside the base-cost formula—is not a fair or transparent way of allocating funds. Because these minimums essentially reward low enrollment, they also discourage smaller districts from expanding (perhaps through interdistrict open enrollment) or consolidating with a nearby district, as they risk losing state dollars by growing in size. Finally, while small districts benefit from this subsidy, public charter and STEM schools—most of which have enrollments under 1,000 students—do not receive staffing minimums in their base-cost calculation. How is that fair?

* * *

School funding formulas are understandably complicated. But the level of complexity and intricacy in the Cupp-Patterson plan puts school funding on increasingly shaky ground. The large expense of maintaining the plan adds to the uncertainty, as legislators may or may not be willing to continue pushing money through the formula to keep it working. And unfortunately, these aren’t the only school funding issues that lawmakers have to worry about. Stay tuned for a follow-up piece, where we’ll examine three more.