This is third in a series in which I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. Previous pieces covered the science of reading and funding for low-income pupils. This essay looks at the way Ohio funds interdistrict open enrollment students.

Since 1989, Ohio has allowed students to attend public schools outside of their home district through interdistrict open enrollment. Under this policy, a student living in Columbus, for instance, can enroll in the neighboring Reynoldsburg school district (and vice-versa). Over the years, a growing number of families have availed themselves of this opportunity and roughly 77,000 students select this option today. Students may be using the program to access schools that offer special programs or courses not offered by their home district. In rural areas, open enrollment may be the only alternative available. And no matter where a student lives, it allows them to attend a different school without needing to call the U-Haul and change homes. As for impacts on learning, a 2017 Fordham study indicates that students, particularly those from less advantaged groups, make academic gains when they open enroll.

Ohio has always allowed districts to choose whether to accept open enrollees, and about four in five do voluntarily participate. Yet in a non-mandatory system, funding is crucial as the dollars tied to open enrollment students serve to incentivize district participation. Unfortunately, as discussed below and previously on this blog, state lawmakers made a misstep in open enrollment funding under the recently enacted Fair School Funding Plan. As data and media accounts suggest, the policy change is putting the program in jeopardy. In the next biennial budget, state lawmakers should restore Ohio’s traditional approach to funding open enrollment.

How open enrollment was previously funded

Under the former version of the state funding formula, open enrollment students were funded at a simple, flat amount. In the last year the old formula was used (FY21), districts across the board received $6,020 per open enrollment student in state funds. This straightforward approach made clear to districts the financial incentive to accept an open enrollee, and the per-pupil amounts were large enough that they likely exceeded the costs of serving additional students (especially in districts not at full capacity). The former approach to funding was clear, straightforward, and helped ensure that districts were covered financially when they decided to permit open enrollment and serve more students.

Recent changes via Fair School Funding Plan

First implemented in FY22, Ohio’s new funding model now treats open enrollees as if they were resident students of the district. Though there is some logic to that approach, the change has significantly cut the funding tied to most open enrollees. The reason: While open enrollment students were previously funded at the full base amount (e.g., $6,020 in FY21), they are now funded at a certain percentage of the base amount. That resulted in particularly sharp declines for more affluent districts—arguably the ones both most in demand, and most in need of convincing to take students from outside their boundaries. But it also reduced funding in average wealth districts, as well, many of which serve Ohio’s rural and small town communities where open enrollment has been relatively common. The new system is also more complicated, making it hard to determine with certainty the precise amounts that open enrollees will bring with them.

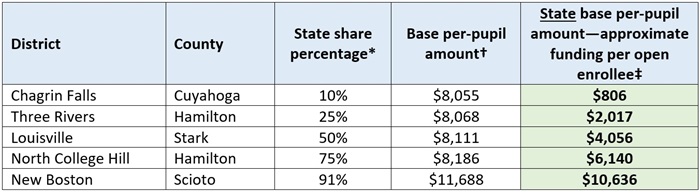

To illustrate, consider table 1, which shows five districts of varying wealth, with Chagrin Falls being the wealthiest and New Boston the poorest. The column shaded in green is key, as it approximates the per-pupil funding of general-education[1] open enrollees attending these districts. In Chagrin Falls, the district receives just $806 per open enrollee—well below what it would have received under the old formula. In Three Rivers, an open enrollee would be funded at just $2,017. Only in higher-poverty districts such as North College Hill does open enrollment funding reach amounts more comparable to the prior formula. In total, just 95 districts—roughly 15 percent—received base amounts this year for open enrollees that exceed $6,020 per pupil.[2]

Table 1: Illustration of open enrollment funding in selected districts, FY24

Downturn in open enrollment participation

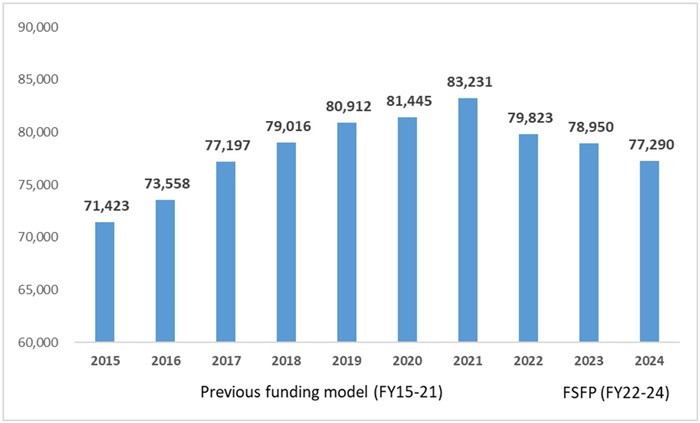

Prior to FY22, participation in open enrollment had been rising at a steady clip each year. Under the new formula, that pattern has reversed. As shown in figure 1, a noticeable decline in participation has occurred over the past three years. Compared to FY21, open enrollment numbers this year are down 7.1 percent (-5,941 students). It is possible that some of the decline from FY21 to FY22 is due to a change in reporting methods.[3] Yet even then, there’s has still been a noticeable slide in enrollments under the Fair School Funding Plan after years of consistent growth.

Figure 1: Open enrollment participation statewide, FYs 2015–24

It may be a coincidence that participation in open enrollment has dipped as the state implemented its new funding formula. Correlation isn’t causation, and perhaps other factors explain these declines (e.g., less parental interest in the program or the expansion of private-school choice).

Or maybe it’s no accident at all. In Northeast Ohio, West Branch school district announced last summer that it would be scaling back open enrollment, pointing specifically to changes in the funding formula. West Clermont, a Southwest Ohio district that open enrolled more than 100 students in 2021, reports just 24 open enrollees this year. A notice on its website confirms that it recently “decreased the number of open enrollment acceptances.” Similarly, Riverside school district says that it’s no longer accepting new open enrollment applications. This spring, Lakota school district near Cincinnati announced that (save for employee children) it’s no longer going to accept open enrollees in grades K–6, period. Impacted open enrollees will be forced to trek back to their home district or seek another educational alternative this fall. All of this is happening at a time when public school enrollment overall is dropping, which would typically lead districts to want to take more students from outside their boundaries.

The path forward on open enrollment funding

Funding policy should encourage rather than discourage districts to meet the needs of more Ohio families and students. The state’s new funding method misses that mark, and without change, we may see even more districts closing off open enrollment opportunities. The best way forward for state lawmakers is to restore the traditional approach to funding open enrollment by setting a simple, flat per-pupil amount that all districts receive when they open enroll.[4] This would once again make clear the financial incentive for districts to accept non-resident students. It would also provide amounts sufficient for districts to maintain or expand their open enrollment program. With any luck, it might even nudge some of the last remaining non-participating districts toward opening their doors.

* * *

For more than two decades, state leaders have crafted choice-friendly policies that put parents and students’ needs first. One part of this push has been to encourage more public-school options within the traditional district system via open enrollment. But recent changes in school funding policy have put this valuable program at-risk. In the next budget cycle, state lawmakers should fix open enrollment funding to ensure that it continues to benefit Ohio families and students.

[1] An economically disadvantaged, special-education, or English learning open enrollee would generate a certain amount above the base funding level for an educating district. In the previous system, an educating district would receive additional dollars from the home district of a special-education student (but not for disadvantaged or English learning students).

[2] Continuing former policy, local dollars do not change hands for open enrollment in the Fair School Funding Plan. Thus, the “gap” created by the new formula’s application of the state share percentage to base funding amounts for open enrollees is not filled through a transfer of local dollars from a home district to educating district.

[3] There is a discrepancy in open enrollment numbers that might reflect a change in reporting. DEW’s FY22 district payment file, which includes the previous year open enrollment numbers, reports 79,595 open enrollees in FY21. However, DEW’s FY21 district payment file reports 83,231 open enrollees (what is displayed in Figure 1).

[4] The amount could be set at the statewide average base per-pupil amount for a given year (in FY24, the average is $8,242 per pupil), or another fixed amount determined by the General Assembly.