In a recent post, I examined three issues with Ohio’s school funding formula—a.k.a., the Cupp-Patterson plan—that Ohio lawmakers should focus on as state budget talks begin early next year. In this piece, we’ll examine three more formula elements that require attention.

Issue 4: Continued use of guarantees

Guarantees are excess dollars that shield districts from funding reductions otherwise prescribed by the formula. They typically come into play when districts are losing students and/or becoming wealthier factors that should lead to a reduced need for state aid under a fair funding formula. But instead of funding schools according to the formula, guarantees provide excess dollars to districts based on their historical funding levels and are often used as a political compromise to shield districts from cuts. At a recent committee hearing, Representative Beryl Piccolantonio noted that “in the final phase-in of the Cupp-Patterson plan, there are not supposed to be guarantees.” She’s right. The plan was routinely billed as one that would finally move Ohio away from guarantees, which were part of the “patchwork” formula that proponents of Cupp-Patterson—and others, including us at Fordham—had long decried.

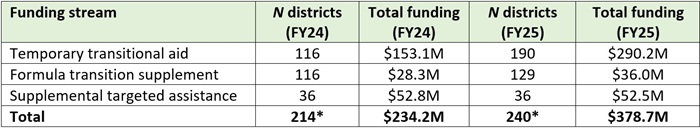

And yet, they have not disappeared. Four years into implementation of the Cupp-Patterson plan, almost two in five districts (240 out of 611) are receiving extra funding via one of the three main guarantees this year,[1] which collectively cost the state $379 million. As table 1 shows, the number of districts on guarantees, and the amount spent, actually went up this year compared to last. If one goes back further to the Kasich-era formula, Ohio is now spending two to three times more on guarantees than it used to (see figure 7 of this report for FYs 2014–17 guarantees). Rather than solving the guarantee problem, we’ve moved backward.

Table 1: Guarantee funding in FY24 and FY25

East Cleveland is by far the largest beneficiary of guarantees, receiving a stunning $8,517 per pupil this year in guarantee funding alone. This largesse sits atop the district’s general formula funding, which amounts to $17,267 per pupil—already multiples above what a typical district receives in state aid. Why is East Cleveland so heavily subsidized? One clue is their enrollments, which have been in freefall over the past few years. In FY20, the district enrolled 1,770 students, but that number was down to just 1,114 students in FY25, a drop of 37 percent. Guarantees have shielded East Cleveland—and other shrinking districts—from reductions that should otherwise occur due to enrollment loss.

Guarantees short-circuit the formula, and lead to unfair and inefficient allocations of state aid. They also consume dollars that could be used to boost funding in other critical areas of education, like funding for low-income students or bold statewide initiatives such as literacy or (hopefully, soon) numeracy reforms. To their credit, proponents of Cupp-Patterson were concerned about guarantees, and suggested they would eventually vanish. In fact, two of the guarantees are actually called “transitional.” In the next budget, lawmakers should complete the “transition” and remove guarantees and move all districts onto the formula. That’s the truly fair way to fund schools.

Issue 5: The DPIA mess

At a press conference unveiling his school funding proposal in 2019, Representative John Patterson admitted that “we have been unable to fully define what ‘economically disadvantaged’ is.” He seemed to be alluding to challenges that Ohio has had in identifying low-income students. Most notably, this includes the problem of relying on free-and-reduced-price meals eligibility as a marker for student poverty. As discussed on this blog before, Ohio began implementation of the Community Eligibility Program (CEP) about a decade ago. This federal initiative allows mid- and high-poverty districts and schools to provide subsidized meals to all students. While this makes sense from a logistics and nutrition perspective, CEP has thrown a wrench in Ohio’s data on economically disadvantaged students. During the 2023–24 school year, sixty-nine districts reported universal disadvantaged rates (>95 percent) in addition to 1,020 individual schools (about one in three). But not every single student attending these districts and schools was actually low-income. Some were actually from higher-income households, and because they received subsidized meals by virtue of their schools’ participation in CEP, they were flagged as disadvantaged.

These identification problems have become a major school funding problem. Economically disadvantaged enrollments are used to determine districts’ disadvantaged pupil impact aid (DPIA). This funding stream is supposed to target extra state aid to meet the needs of low-income students. But due to the inflated headcounts, DPIA no longer effectively drives dollars to the highest-need schools. Some mid-poverty districts—those with a mix of students from varying economic backgrounds—are now receiving just as much DPIA funding as districts with more concentrated poverty. For instance, Euclid school district near Cleveland receives the same DPIA per pupil as the Cleveland school district because both participate in CEP and report 100 percent economically disadvantaged rates. Yet we know from Census data,[2] as well as pre-CEP data, that Euclid enrolls fewer low-income students than Cleveland.

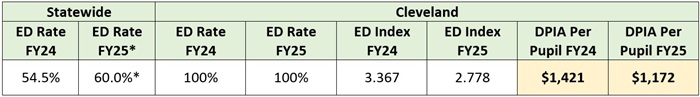

Yet another issue that’s surfacing as CEP continues to expand across the state[3] is that high-poverty districts are now seeing their DPIA funding cut. It’s easiest to see using Cleveland as an illustration. Table 2 shows that the state average disadvantaged rate has moved upward, as more schools participate in CEP and report 100 percent rates. This causes the economically disadvantaged “indexes” of high-poverty districts to fall. Because these indexes are critical to determining funding, the actual DPIA amounts fall with it. Cleveland, for instance, has seen its DPIA funding cut by $249 per pupil within the past year. This hasn’t gone noticed by Cleveland administrators, and is likely to get the attention of other high-poverty urban districts and charter schools that face a similar situation.

Table 2: Cleveland Metropolitan School District’s DPIA index and funding amount, FY24 and FY25

The next General Assembly needs to clean up the DPIA mess. To do this, lawmakers must do two things. First, they should require DEW to identify low-income students based on direct certification, a process that’s already in use and identifies disadvantaged pupils through their families’ participation in SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid. Second, they should use direct-certification numbers to allocate DPIA funds, instead of the inflated economically disadvantaged rates based on meals eligibility. These steps would strengthen the equity of Ohio’s funding system by ensuring that low-income students are accurately identified and receive the resources they need from the state.

Issue 6: Weakened incentives for interdistrict open enrollment

Ohio has long had an interdistrict open-enrollment policy that allows students to attend district schools outside of the district where they live. Students benefit from this option, as they can attend public schools with programs and courses that may better fit their needs and interests or that aren’t offered by their home district. Other students may choose to attend school near extended family, or even one that is located closer to their home if they live near a district boundary. Fordham research has found that students who participate in open enrollment make academic gains, especially minority pupils who leverage the program to access higher-quality schools.

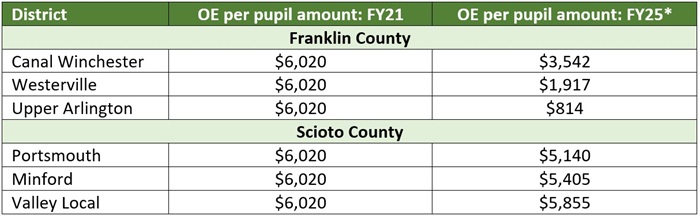

While most districts participate in open enrollment, they are not required to do so under law—and, alas, many suburban districts do not open their doors to non-residents. In such a voluntary program, the financial incentive to participate in open enrollment matters greatly. Under the state’s previous funding model, districts received $6,020 per open-enrollment student from the state.[4] That system made crystal clear the financial incentive and the amount likely covered the incremental cost of serving additional students.

Cupp-Patterson, however, changed course on open-enrollment funding. Instead of providing a simple, flat amount that applies across the state, the model now funds open enrollees at the state share of the base per-pupil amount of their district of attendance. Since that amount varies widely across districts and can only be found by digging deep into state funding reports,[5] this change muddies the incentive to allow open enrollment. Worse yet, this approach results in declining per-pupil funding for open enrollees in many districts, particularly higher-performing (often wealthier) ones where students stand to gain the most if they attend. The reason for the slippage is that state share percentages (SSPs) are now applied to the base amount.

Table 3 shows how this plays out using Franklin and Scioto County districts as illustrations. Under the old formula, all six of these districts would receive $6,020 per open enrollee. Now, however, they receive variable amounts. In the wealthier suburban Columbus districts, these amounts are much lower than under Cupp-Patterson, which offers them almost no incentive to participate in open enrollment. Rural Scioto County districts are less impacted by the change—they are less wealthy and receive higher amounts of state aid—but they still receive somewhat reduced open-enrollment funding. Remember, these comparisons are against a FY21 baseline; had the old formula been continued, the base amount would almost surely be higher today.

Table 3: Open-enrollment funding under the old formula (FY21) and Cupp-Patterson (FY25)

There is anecdotal evidence that some districts are responding to these weakened incentives by curtailing open enrollment. As a result, participation has slid over the past four years. In FY22, the state reported 79,823 open enrollees, but in FY25, just 74,557 students are in the program. This decline comes in the wake of years of consistent growth in open enrollment under the prior funding model.

State lawmakers should address open-enrollment funding to keep this option on the table for Ohio students. They have a couple policy options that would fix the problem. First—and more ideally—they could once again use the full base amount to fund open-enrollment students ($8,242 per pupil is the statewide average this year). This would make clear the incentive for open enrollment and increase funding amounts. Alternatively, legislators could use the higher of the student’s home district or district where the student attends state share of the base amount for open enrollees. While more complicated, this approach would ensure that students from, say Cleveland or Akron, aren’t funded at small amounts when they open enroll at a suburban district.

***

With much fanfare, Ohio lawmakers enacted a new school funding formula in summer 2021. The Cupp-Patterson plan certainly has its strengths. But as it has been implemented, problems have also been revealed. With any luck, lawmakers will make fixes in the next state budget that move Ohio towards a system that actually lives up to its popular name and is a “fair school funding model.”

[1] The staffing minimums in the base-cost model could be considered a guarantee, and there is also one inside the transportation formula.

[2] SAIPE Census data from 2022, which estimates the percentage of school-aged children at or below the federal poverty level, indicates that Euclid has a poverty rate of 31 percent versus Cleveland’s rate of 41 percent.

[3] This is happening as the result of a very recent federal policy change that has lowered the bar for CEP eligibility.

[4] This is the FY21 amount, the last year the old formula was in use. If applicable, districts also received CTE weighted funding and could also seek additional funds from a student’s home district to cover special-education costs at the end of the year.

[5] This is even more complicated than it sounds, as districts have not been receiving the actual base amounts prescribed by the formula during the phase-in of Cupp-Patterson.