As it has for much of the past two years, the Ohio House is currently discussing the latest version of the Cupp-Patterson funding plan, a significant rework of the state funding formula. The legislation (House Bill 1) may again sail through the lower chamber this spring, but whether it passes the Senate and garners the signature of the governor is another matter. While the plan has its strengths, a number of questions remain, most notably around its estimated $2 billion per year price tag.

The plan’s overall cost should be a first-order concern, but its policy details also merit attention. Lawmakers shouldn’t enact a system that future legislators will deem unsustainable and need to fix down the road.

With that in mind, the following piece examines one important aspect of the Cupp-Patterson model that hasn’t received much scrutiny thus far—its approach to setting a “base amount.” Note that this essay doesn’t address other concerns, already discussed on this blog, such as the absence of reforms that encourage wise spending or the inequitable treatment of charters. A forthcoming piece will tackle two additional issues: guarantees and interdistrict open enrollment.

Determining a base amount

One of the foundational elements of most funding formulas is a base amount, which is usually seen as representing the minimum cost of educating a typical student without any disadvantages or special needs. A distinctive feature of the Cupp-Patterson model is its extensive calculations that attempt to capture the cost of educating students, which is then used to determine districts’ base funding.

Before going any further, it must be noted that there is no settled way of determining the cost of educating a typical student. Analysts and consultants have developed a range of approaches that rely on different assumptions and methods, and that sometimes produce wildly varying results. For instance, during the early 2000s, two teams of analysts worked to gauge the costs of educating students in Texas and came up with estimates that were billions of dollars apart and equivalent to more than 10 percent of the state’s total education spending.

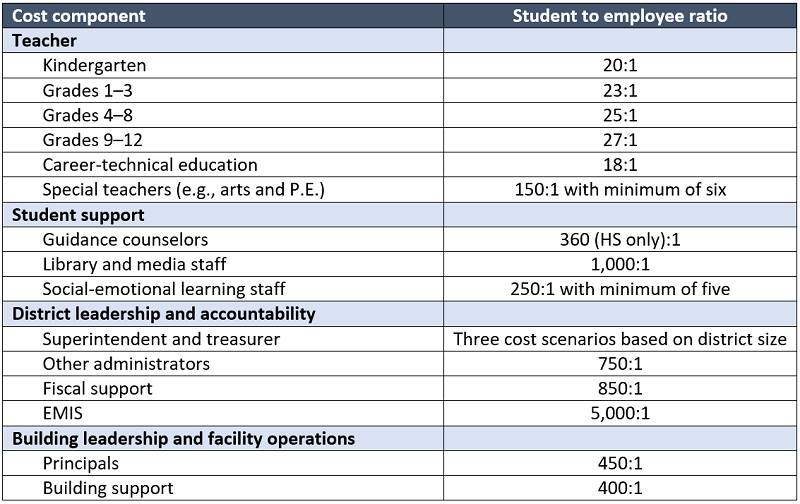

Despite the unsettled “science,” the Cupp-Patterson developers took a stab at estimating the costs and chose to implement an inputs-driven model that focuses on staffing ratios and salary data. The table below displays the major components of the formula. For instance, the framework provides one teacher per twenty-five students in grades four through eight. Thus, if a district has 100 students in those grades, its costs for that component would be four teachers times the average statewide teacher salary plus benefits. These computations, which would be written into statute, directly determine districts’ base amounts.

Table 1: Base cost calculations under the Cupp-Patterson funding plan

Note: Some elements that don’t rely on staffing ratios are omitted (e.g., supplies, building maintenance, and professional development). Districts are not required to actually implement these ratios as they are used only to calculate costs.

Because districts have different enrollment patterns, the Cupp-Patterson plan yields variable base amounts. According to LSC, these range from $7,000 to a whopping $15,000 per pupil, depending on the district. The base amounts of most districts (86 percent) fall between $7,000 and $8,000 per pupil, with a statewide average of $7,199 per pupil. This is a major shift from Ohio’s current approach to base funding, one that is also used by a majority of states. Rather than including cost calculations, the present formula sets a fixed amount that applies to all districts (currently $6,020 per pupil).[1]

It’s also important to note that, although the base amount applies to the core component of the state funding formula, it does not reflect the entirety of district revenue. Ohio districts receive billions more from state “categorical” funding (e.g., extra dollars for special education and economically disadvantaged students), supplemental local property taxes, and federal aid.

Concerns with the Cupp-Patterson approach

There are tradeoffs to these different approaches. The current formula’s fixed amount could be viewed as positive feature. It’s a straightforward and transparent way of setting the base, as it allows anyone to examine state law and find every district’s base printed in black and white. A fixed amount could also give legislators more budget flexibility. A simple change in dollar amounts can address a fiscal crisis, adjust funding for inflation, or boost expenditures above and beyond inflation. In fact, if legislators are intent on increasing education spending, they could simply ratchet up the current base amount to, say, $6,800 per pupil. On the other hand, the biggest criticism of a fixed base is that it’s often seen as an arbitrary figure, one that isn’t necessarily tied to the cost of educating students.

Now to the Cupp-Patterson plan. The advantage of this model is that it more explicitly links base amounts to costs, something that its advocates have routinely pointed out. They have also contended that putting the entire cost model into state law is more transparent, as one can see the “cost drivers” of education. Yet there many potential problems with the method, as well.

- The wide variation in base amounts might lead one to question the assumptions that are inherent in the cost model. For example, why do a few districts have such astronomical bases—up to $15,000 per pupil? Which districts are the outliers? (Honest questions, as I have not seen individual district’s base amounts reported.) Since there is no fixed amount set in legislation—only calculations—it’s hard to decipher what exactly is happening inside the black box.

- The ratios in the cost model are arbitrary and could easily be changed by future legislators. For instance, the student-to-teacher ratios are grounded in nothing more than subjective judgments. As a result, legislators could face intense pressure in future years to reduce ratios and thereby increase the state’s funding obligations. Though less likely, they might also increase the ratios in an effort to cut funding.

- The use of statewide average employee salaries and benefits is also questionable. For one, these data reflect compensation derived from total district revenue in FY 2018—not dollars received specifically through the base funding formula. Moreover, akin to the ratios, the use of statewide averages could also be viewed as an arbitrary decision, not one tied to the actual costs faced by each district. For instance, districts in pricier areas of the state may face higher staffing costs than the average district. That being said, using a district’s own salary data in the model risks another set of problems, as it directly incentivizes inflated payrolls (see point five).

- The cost calculations would need to be recomputed at some point, likely putting the state on the hook for further spending hikes in future years.[2] House Bill 1 relies on FY 2018 statewide employee salary and benefits data to compute districts’ base costs—those data are the basis for the $2 billion per year cost that takes six years to fully implement. But what happens when the phase-in period ends? In all likelihood, there will be calls to recompute costs using up-to-date salary and benefits data. In that case, the state will be staring down another spending increase because it hasn’t gradually increased funding with inflation.

- Although not an immediate concern because House Bill 1 relies on data from 2018, a model driven by employee salaries and benefits could create incentives for districts to inflate costs. If districts know that the state will regularly recompute costs, they have good reason to push salaries and benefits upward. Why? The state will be obligated to spend more on education—a good thing for school employees—if salaries and benefits are on the rise. At the least, there will be less incentive for districts to contain payroll costs when those are passed on to the state.

While many have praised the base-cost model of the Cupp-Patterson plan, legislators should step back and rethink whether putting the entire cost model into state law is a wise idea. If they feel a need to link the base with costs, they could disclose the calculations in a report. But putting the whole framework into statute might leave future legislators dealing with runaway spending—or facing cries (or litigation) arguing that they are failing to fund the state’s school funding model.

[1] In both the Cupp-Patterson model and Ohio’s current formula, a district’s base amount is adjusted to account for its local tax capacity (including a state-required minimum 2 percent property tax).

[2] House Bill 1 creates a nineteen-member School Funding Oversight Commission that would make recommendations about future modifications to the funding formula, including adjustments for inflation.