Through its science of reading initiative, Ohio is devoting significant resources to strengthening literacy across the state. Boosting reading proficiency is essential, and this ambitious effort holds great promise to do just that. Yet instruction in other subjects—including math, most critically—shouldn’t get lost in the shuffle. As a recent study from the Urban Institute indicates, increased math performance delivers even stronger long-term returns for students—specifically, higher earnings as adults—than improving reading skills. At a more global level, Stanford University’s Eric Hanushek and colleagues have found that national performance in math is highly correlated to countries’ economic prosperity.

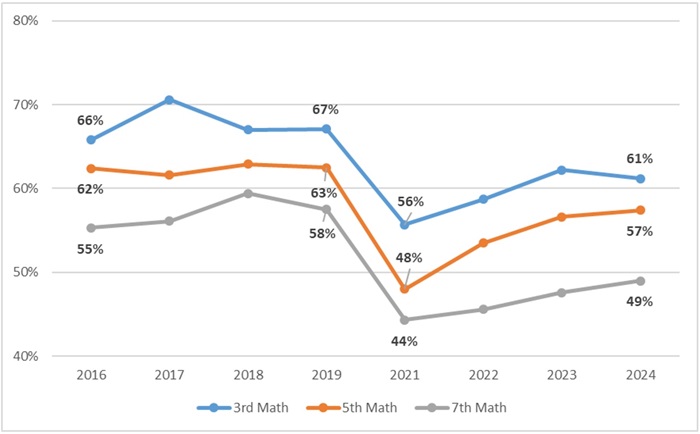

In short, numeracy matters immensely. But math achievement in Ohio and nationally has long been lackluster—and it got much worse during the pandemic. Figure 1 shows the trends in Ohio’s math proficiency rates in grades three, five, and seven. Prior to the pandemic, roughly 55 to 70 percent of students were proficient in math, depending on grade and year. Those rates fell to record lows by 2020–21. They’ve ticked upward since then but still fall significantly behind pre-pandemic levels and remain far below what any state should expect of its students.

Figure 1: Ohio’s math proficiency rates in elementary and middle school grades, 2015–16 to 2023–24

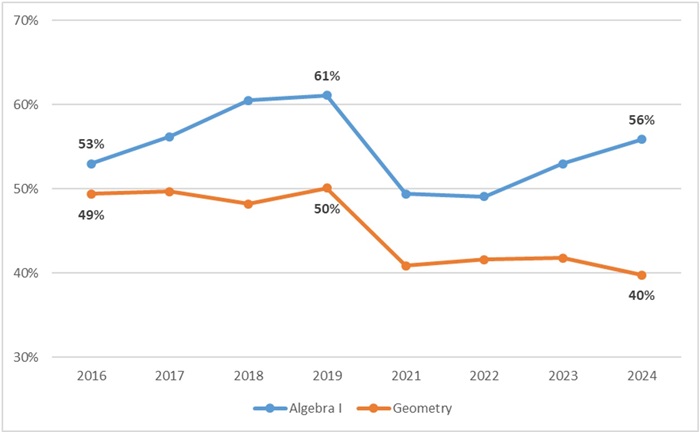

Similar patterns emerge in high school. In Algebra I, we see a sharp decline in proficiency during the pandemic followed by some recovery. But there’s no sign of post-pandemic recovery in geometry. Moreover, while not displayed below, some districts’ math proficiency rates are downright abysmal. In 2023–24, just 18 percent of Columbus City Schools’ students were proficient in Algebra I and 11 percent in geometry. (Fewer than one in five!) In South-Western, the second largest district in Franklin County, just 29 percent reached achieved proficiency in geometry, though a more respectable 56 percent met that mark in Algebra I.

Figure 2: High school proficiency rates in high school Algebra I and geometry, 2015–16 to 2023–24

Just as they did with reading, state policymakers need to step up to boost the math proficiency of young Ohioans. While it may be tempting to copy and paste the state’s literacy efforts, that’s not the best path forward. The challenge, as a trio of math scholars recently noted, is that “there is less available research on math-related interventions and instructional practices than in reading.” With a smaller evidence base, it’s harder to pinpoint specific curricula, practices, and programs that should be encouraged—or even required—as well as ones that should be discontinued.

That said, math experts have put their finger on key elements that ought to guide math instruction. In 2001, the National Research Council (NRC) identified five “strands” of math proficiency, which were later echoed by the National Mathematics Advisory Panel (NMAP) in 2008 and are generally accepted by experts and educators today. One strand is “procedural fluency,” which includes knowing times tables by heart and mastering the standard procedures used to solve problems (e.g., carrying a digit when adding). Another strand is “conceptual understanding,” which is the ability to comprehend math concepts and relationships. For example, the NRC report notes that when students understand that addition is commutative (e.g., 3+5=5+3), they have to memorize half the addition combinations. Though procedural fluency and conceptual understanding are sometimes viewed as competing approaches, both the NRC and NMAP reports emphasize that they are equally essential to proficiency and they complement each other.[1] As for more practical assistance for math teachers, the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) has released several practice guides over the past two decades.[2] Its most recent math-related guide from 2021 offers six strong (“tier 1”) evidence-based recommendations for elementary math instruction.

Translating these concepts—as well as other research-backed ideas—into concrete policy is no easy task. But difficult doesn’t mean impossible, and here are six ideas that Ohio lawmakers should pursue to increase math proficiency.

- Require the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) to undertake a review of core math curricula. Ohio’s literacy initiative has rightly centered on ensuring schools use high-quality curricula aligned to the science of reading. Those efforts have included reviews of the reading curricula available to Ohio schools and compiling a list of high-quality instructional materials. In similar vein, lawmakers should direct DEW to review the core math curricula (grades K–12) that are currently on the market to assess their alignment with state math standards and the NRC/NMAP concepts, as well as effective practices identified by WWC and other math experts.[3] In its review, the department should take seriously EdReports’ ratings, which award strong marks to well-respected curricula such as Eureka Math and Illustrative Math. This process would yield a list of recommended high-quality math curricula that can help inform schools’ decisions about math curriculum moving forward.

- Increase public transparency regarding which math curricula schools are using. Thanks to the state’s recent literacy reforms, we know more about schools’ elementary reading curricula. But we know virtually nothing about math. That should change, as math curricula choices are crucial to the quality of instruction. To provide more sunlight about which math programs are in use, legislators should require all public schools to report to DEW their core math curricula. The agency should in turn disclose schools’ math and reading[4] curricula on schools’ state report card, while also including an indicator about whether they appear on the state’s recommended list.

- Ensure prospective elementary school teachers have strong content knowledge by requiring them to pass the math section of their licensure exam. Teachers cannot effectively teach math if they don’t understand it. That’s common sense and also supported by research. While Ohio does check middle and high school math teachers’ content knowledge via passage of a math-specific licensure exam, it does not do so for elementary teachers. Instead, teachers applying for the grades PK–5 elementary license take a composite content knowledge exam that includes math, but also sections on literacy, science, social studies, and the arts.[5] To pass the test, prospective teachers are only required to earn an overall passing score. That means a future elementary teacher could fail the math section but still pass the test based on their competency in other subjects. Given the importance of math—and the likelihood that an elementary teacher will be asked to teach math—state lawmakers should require prospective elementary school teachers to pass the math section of the content knowledge exam in addition to earning an overall passing score.

- Require early identification and support for children who are struggling in math. Another way to bolster math in elementary schools is to enact a statewide requirement for schools to screen all students in grades K–3 and identify those with significant math deficiencies. Parents of children who are identified as being off track should be notified, and schools should create a math improvement plan for the student. These screening, notification, and plan requirements could mirror Ohio’s current reading requirements in grades K–3. In schools with significant numbers of off-track students in math, the state should provide additional instructional help by providing math coaches (akin to its literacy coaching initiative).

- Encourage tutoring that adheres to quality standards for high-dosage tutoring and effective math practices. As has been widely discussed in the context of post-pandemic academic recovery, high-dosage tutoring (HDT) has historically boasted a strong evidence base. Unfortunately, recent studies suggest that pandemic-era implementation of HDT has been uneven and the results mixed. But when it’s done well, the extra time and support provided by HDT can significantly boost achievement. Ohio should continue to promote tutoring—perhaps via a math-focused HDT grant program[6]—but policymakers must be more insistent that the programs adhere to quality standards for HDT. These include that tutoring be provided in-person, with a consistent tutor, during the school day, in small groups (less than five students), and for at least three times a week for thirty to sixty minutes. HDT in math should also, of course, align with effective math instructional practices.

- Promote “double dosing” and advanced math in high school. Another “more time on task” option with a track record of success is double dosing, especially in Algebra I. In this model, students participate in two periods of daily math instruction, ideally with the same teacher. One period is focused on direct instruction, while the other is dedicated to additional practice and support. Devoting extra time to Algebra I, in particular, may have stronger rationale, as this course remains a crucial gateway to the more advanced math needed for college and technical professions. State policymakers should encourage double dosing in high schools and spotlight schools effectively deploying this approach. They could consider putting money behind it, too, though double dosing is not likely to be as expensive as HDT, which requires additional staff. Finally, state policymakers should strongly encourage—for students who are ready—Algebra I in eighth grade and advanced coursework during high school. To support that goal, state lawmakers should create an automatic course enrollment policy for high-achieving students.

As with literacy, numeracy is crucial to students’ long-term success, as well as the economic growth of the state. Foundational math skills are essential to carrying out all manner of daily tasks, from managing personal finances to measuring the ingredients in a recipe. Meanwhile, more advanced math—and the rigorous and logical thinking it supports—is necessary for success in higher education and many of today’s occupations. There is a lot of work ahead to ensure that all Ohio students achieve math proficiency. Let’s get cracking.

[1] The other three strands are “strategic competence,” “adaptive reasoning,” and “productive disposition.” The Colorado Department of Education has a concise summary of all five components.

[2] In the area of math, WWC has published practice guides for grades 6–12 algebra instruction (2019), grades PK–K math instruction (2013), grades K–8 fractions instruction (2010) and grades 4–8 mathematical problem solving (2012).

[3] NMAP noted the massive length of many math textbooks, often running hundreds to a thousand pages, and that other high-performing countries use much slimmer texts. Curricula usability (for both teachers and students) should likely be considered, as well.

[4] Reading curriculum disclosure on the report card is not currently required under the state’s early literacy initiative.

[5] They must also pass the literacy-specific Foundations of Reading licensure test, along with a pedagogical test.

[6] With support from federal Covid-relief funds, Ohio has implemented a few tutoring initiatives in recent years. Those dollars have expired, and state lawmakers would need to set-aside state funds to support future tutoring initiatives.