- Want a good read? Check out this little nugget on the Fordham-sponsored United Schools Network of charters here in Columbus, including a look at their new School Performance Institute. Just ignore the snarky subhead of the piece. They couldn’t help themselves, I suppose. (Columbus Monthly, 11/14/17)

- Sticking with the theme of good news for a moment, Dayton City Schools’ report card improved ever so slightly this week after a fix of some erroneous data as processed by the Ohio Department of Education. (Dayton Daily News, 11/13/17) The aforementioned erroneous data had to do with one aspect of graduation rates. The ways in which students reach graduation have, as my loyal Gadfly Bites subscribers are painfully aware, been a subject of much angst in various halls of state government for a year or more. Graduation pathways were front and center again during this week’s state board of education meeting. Specifically, three options were presented to the board by ODE regarding the current grad requirements, which includes a non-academic pathway which applies only to the Class of 2018. For now. (Dayton Daily News, 11/13/17) I have to apologize to all four of my loyal Gadfly Bites subscribers for missing a subtle but important shift in the discussion of graduation requirements that occurred earlier this year when the state board of education decided to impanel a committee to study the topic and report back with recommendations. Despite previous talk of a “temporary fix” and “one time opportunity” to address the possible “graduation rate apocalypse” for the Class of 2018, all that went away when the committee’s recommendations arrived. That is why the state board seems to have abandoned talk of only needing an “adjustment period” for the Class of 2018 to get used to the not-as-new-as-it-used-to-be end of course exam pathway and is now debating whether to make permanent the lowered bar. Indeed, it seems there may be additional non-academic pathways that may jump into the discussion coming up. (Columbus Dispatch, 11/14/17)

- That bill we told you about proposing to ban out-of-school suspensions for most infractions for students in Pre-K to grade three was introduced with some fanfare yesterday. Let’s take a quick roll call. Senator O’Donnell of Journalist Party still appears to be a Yes. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 11/14/17) How about Senator Jeremy Kelley (J-Dayton), from whose district the bill’s sponsor hails? Seems undecided at this point. (Dayton Daily News, 11/14/17) Cincinnati City Schools’ efforts to lower suspensions and expulsions seem to be key inspiration for certain provisions of this bill. What says Senator Jessie Balmert, also of the esteemed Journalist Party, who hails from the Queen City? Seems to be leaning in favor, if I say so myself. (Cincinnati Enquirer, 11/14/17)

- Speaking of Cincinnati, here is a look at how the citywide Preschool Promise program is faring one year after passage of the levy that created it. It’s a long piece with lots of details, most of which don’t sound that great to me, and kids in slots takes up a very small part of it. And those numbers aren’t so great either. If some of this sounds familiar, you can just sub in “Dayton” for “Cincinnati” in some spots and you’ll know why. If anyone cares, I think Cincy’s efforts and outcomes actually seem less good than Dayton’s, but that’s really just degrees of “not-so-hotness” not worth quibbling over. (Cincinnati Enquirer, 11/14/17)

- Yesterday was the third annual Ohio Online Learning Day, which included a rally at the Statehouse of parents, students, school officials, politicians, and advocates. Gongwer covered it. It’s a mildly interesting story, but for those of you who have to – due to your job of, say, reading and compiling education news clips – have to read the full text of such reports, this one is a particular ordeal due to rampant typos, the odd grammar mistake, and errors of reportage. I’m sorry. “Scare resources” indeed. (Gongwer Ohio, 11/14/17)

- Elementary students in Youngstown are apparently really digging the new “Y-Bucks” program in which they can earn bucks for good behavior and use them to buy cool stuff at the Y-Stores in their schools. This all sounds pretty good – if maybe a bit familiar from some charter schools I could name – but I do have some lingering questions regarding the anecdote of the shoes. (Youngstown Vindicator, 11/15/17) Finally today, I give you Urban Squash Cleveland. No, it’s not about farming. It’s about sports. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 11/14/17)

A recent study on career and technical education examines whether taking “CTE” courses in high school has any relationship to dropping out of high school and, conversely, going to college.

Data come from the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002 and follows a cohort of public school students starting in the second half of their sophomore year (2002), surveying them again in both spring 2004 and spring 2006 when they would have been in their second year after high school graduation. Analysts attempt to control for a wide range of demographic, family, academic, attitudinal, and school-level variables, such as parental education, family income, poverty level of school, college expectations, etc. While they have loads of control variables, the study is nevertheless not causal, in part because it is not able to control for all of the unobserved factors that may make students who enroll in CTE different from those who do not.

The key finding is that taking more CTE courses is linked to a lower chance of dropping out of high school. Specifically, taking any CTE course in high school decreases the odds of dropping out by 1.2 percent for each course, so the more the better, but taking a CTE course in eleventh or twelfth grade is even more beneficial: those same odds decrease by 1.6 percent.

As for on-time graduation, there are positive benefits here too. Specifically, CTE boosts the probability of on-time graduation by 1.6 percent for every course completed, with courses taken in the later high school years showing more significant benefits. Obviously not all students progress through to the next grade (the two follow-up surveys ask them if they dropped out), so keep in mind that we are observing only the “survivors” as the years roll on.

Regarding college-going behavior, analysts found no relationship between CTE course-taking behavior and whether students went to college right after high school.

Last year we published a study by Shaun Dougherty that also found positive impacts of CTE. Specifically, concentrating (taking three or more CTE courses) increased the probability of graduating from high school and of enrolling in a two-year college. The current study did not find post-secondary impacts, which makes you wonder whether concentrating in CTE makes the difference. (Incidentally, our 2016 study also found that concentrators were more likely than non-concentrators to be employed and that low-income students see the most benefits from concentrating.)

Given the considerable interest in career and technical education by students, parents, teachers, researchers, and funders, it’s heartening to see a growing number of studies find positive results. One question that needs more empirical investigation: How can CTE programs be structured to better benefit both students and employers? Stay tuned in 2018 for what we have to say about that.

SOURCE: Michael A. Gottfried and Jay Stratte Plasman, “Linking the Timing of Career and Technical Education Coursetaking With High School Dropout and College-Going Behavior,” American Educational Research Journal (October 2017).

“Collective efficacy” is the sense among group members that they have the capability to organize and execute the actions required to achieve their most important goals. Researchers have, for twenty years, tested it as a key factor in explaining performance differences among groups attempting the same task in areas such as healthcare and manufacturing. The literature on collective efficacy in K–12 education is new and growing, spearheaded largely by Roger D. Goddard of The Ohio State University. A new report by a group of researchers led by Dr. Goddard seeks to unite quantitative and qualitative data on the subject.

The quantitative portion of the analysis was fairly straightforward, looking at the math achievement levels of 13,472 fourth- and fifth-grade students on a mandatory assessment given annually in one large district in Texas. Change between the two years of scores was the sole academic measure utilized and researchers looked at achievement gaps between different school buildings and between black and white students. A measure of collective efficacy was derived using a twelve-item survey, which was administered to 2,041 teachers. The survey rated teachers’ level of agreement on a scale of one to five with statements such as, “Teachers are here to get through to the most difficult students.” Statements addressed each individual’s perception of group competence and “analysis of the teaching task.” A single collective efficacy score for each building was made up of the mean of the twelve aggregated item scores.

After controlling for student and school demographic characteristics, a one standard deviation increase in collective efficacy was associated with a 0.1 standard deviation increase in mathematics achievement—a small but statistically significant predictor. More striking was the finding that a one standard deviation increase in collective efficacy was associated with a 50 percent reduction in the math achievement gap between black and white students. In short, schools whose teachers believe they have the capability of raising the math achievement of their students—all of their students—will apparently do so.

There are, of course, caveats to the findings, including the large Latino student population in the district whose achievement levels were not specifically analyzed (remember: the study looked only at the white-black achievement gap), and the difference between teaching math and less skills-based subjects like English and social studies, which might resist even the highest levels of collective efficacy. But we have seen evidence that odder things than teachers’ belief in themselves, and their students, may influence achievement.

Convinced of the positive connection between collective efficacy and math achievement, the researchers also sought to understand the factors that influenced schools’ relative collective efficacy scores. This was accomplished by way of teacher focus groups held at six selected schools—split evenly between high and low collective efficacy scores. The responses were nuanced and wide-ranging, but collective efficacy scores were most strongly correlated with perceptions of support from school leadership and perceptions of peers’ own efficacy and positive role modeling. The more supportive school leaders were perceived to be of teacher collaboration, instructional improvement, etc., the higher a school’s collective efficacy score. And the more teachers described their peers as having a sustained focus on instructional improvement (increased instructional time, no excuses for low performance, etc.), the higher a school’s collective efficacy score.

Collective efficacy is about “organizing and executing the courses of action required” for a group to achieve a goal. If the group has the sense that they are capable, research seems to indicate that they are more likely to succeed at organizing and executing. If that is true, then it seems like collective teambuilding is probably a better sign of success than, say,, collective bargaining.

SOURCE: Roger D. Goddard, Linda Skrla, and Serena J. Salloum, “The Role of Collective Efficacy in Closing Student Achievement Gaps: A Mixed Methods Study of School Leadership for Excellence and Equity,” Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (October, 2017).

The Every Student Succeeds Act grants states more authority over their accountability systems than did No Child Left Behind, but have they seized the opportunity to develop school ratings that are clearer and fairer than those in the past? Our new report, Rating the Ratings: Analyzing the 51 ESSA Accountability Plans, examines the plans submitted by all fifty states and the District of Columbia, and whether they are strong or weak (or in-between) in achieving three objectives:

- Assigning annual ratings to schools that are clear and intuitive for parents, educators, and the public;

- Encouraging schools to focus on all students, not just their low performers; and

- Fairly measuring and judging all schools, including those with high rates of poverty.

Key findings include:

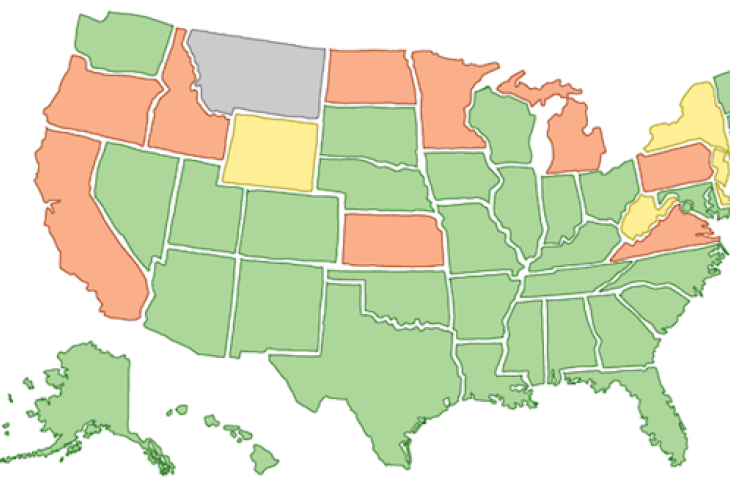

- Thirty-five states—69 percent—received a "strong" grade for using clear and intuitive ratings such as A–F grades, five-star ratings, or user-friendly numerical system. These labels immediately convey to all observers how well a given school is performing, and is a major improvement over the often Orwellian school ratings of the NCLB era.

- The country is also doing much better in signaling that every child is important, not just the "bubble kids" near the proficiency cut-off. Twenty-three states earned strong grades on this objective, and another fourteen earned medium marks.

- There is somewhat less progress when it comes to making accountability systems fair to high-poverty schools. Only eighteen states are strong here. But twenty-four others earn a medium grade, which is still an improvement over NCLB.

Altogether, twenty-one of the fifty-one proposed school rating systems are either good or great—earning at least two strong grades and one medium. And those of eight states—Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington—are the best, having received perfect scores. Moreover, of all the ratings we assigned across the three objectives, 50 percent were strong and 29 percent were medium.

On the flip side, three states received weak grades in each of the three areas: California, Idaho, and North Dakota. They rely on proficiency rates, don’t emphasize student growth, and propose using a dashboard-like approach with myriad data points and no bottom line for reporting school quality to parents, beyond identifying their very worst schools, as required by federal law.

Although many states included elements in their school rating systems that we don’t love, it’s welcome news that so many have corrected NCLB’s biggest flaws. Moreover, none of these ESSA plans are set in stone, and we hope that states will return to the drawing board to make their systems better before too much time passes. Congress probably won’t get around to reauthorizing the law for a decade or more. States need not—and should not—wait that long to make improvements.

But that is a conversation for another day. For now, let’s celebrate the fact that states, by and large, seized the ESSA opportunity to make their school accountability systems clearer and fairer. In this era of political dysfunction, that’s no small thing.

The Every Student Succeeds Act grants states more authority over their accountability systems than did No Child Left Behind, but have they seized the opportunity to develop school ratings that are clearer and fairer than those in the past? Our new analysis examines the plans submitted by all fifty states and the District of Columbia, and whether they are strong or weak (or in-between) in achieving three objectives:

-

Assigning annual ratings to schools that are clear and intuitive for parents, educators, and the public;

-

Encouraging schools to focus on all students, not just their low performers; and

-

Fairly measuring and judging all schools, including those with high rates of poverty.

Key findings include:

-

Thirty-five states—69 percent—received a “strong” grade for using clear and intuitive ratings such as A–F grades, five-star ratings, or user-friendly numerical systems. These labels immediately convey to all observers how well a given school is performing, and is a major improvement over the often Orwellian school ratings of the NCLB era.

-

The country is also doing much better in signaling that every child is important, not just the “bubble kids” near the proficiency cut-off. Twenty-three states earned strong grades on this objective, and another fourteen earned medium marks.

-

There is somewhat less progress when it comes to making accountability systems fair to high-poverty schools. Only eighteen states are strong here. But twenty-four others earn a medium grade, which is still an improvement over NCLB.

Altogether, twenty-one of the fifty-one proposed school rating systems are either good or great—earning at least two strong grades and one medium. And those of eight states—Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington—are the best, having received perfect scores. Moreover, of all the ratings we assigned across the three objectives, 50 percent were strong and 29 percent were medium.

On the flip side, three states received weak grades in each of the three areas: California, Idaho, and North Dakota. They rely on proficiency rates, don’t emphasize student growth, and propose using a dashboard-like approach with myriad data points and no bottom line for reporting school quality to parents, beyond identifying their very worst schools, as required by federal law.

Although many states included elements in their school rating systems that we don’t love, it’s welcome news that so many have corrected NCLB’s biggest flaws. Moreover, none of these ESSA plans are set in stone, and we hope that states will return to the drawing board to make their systems better before too much time passes. Congress probably won’t get around to reauthorizing the law for a decade or more. States need not—and should not—wait that long to make improvements.

But that is a conversation for another day. For now, let’s celebrate the fact that states, by and large, seized the ESSA opportunity to make their school accountability systems clearer and fairer. In this era of political dysfunction, that’s no small thing.

| Select One of the Following to View Its State Profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | GA | MD | NJ | SC |

| AK | HI | MA | NM | SD |

| AZ | ID | MI | NY | TN |

| AR | IL | MN | NC | TX |

| CA | IN | MS | ND | UT |

| CO | IA | MO | OH | VT |

| CT | KS | MT | OK | VA |

| DE | KY | NE | OR | WA |

| DC | LA | NV | PA | WV |

| FL | ME | NH | RI | WI |

| WY | ||||

Editor's note: On November 15, 2017, one of New Hampshire's ratings was changed from weak to strong, and the report and accompanying text were updated accordingly. The original rating of weak was incorrect.

Youngstown City School’s CEO Krish Mohip recently announced significant changes to how his district will evaluate its teachers.

Under Mohip’s new system, 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation score will be based on classroom observations of instruction and 50 percent will be based on student growth. So far so good; on its face, this is identical to the state’s original evaluation framework. The difference between the two is how student growth is measured. Under the state’s system, value added scores and vendor assessments are supplemented, when needed based upon the subject and grade level taught, by locally determined measures. Mohip, on the other hand, plans to evaluate individual teachers based on the entire district’s progress using only one student growth measure—shared attribution.

For those who are unfamiliar, shared attribution is the practice of attributing value added scores—which are largely determined by ELA and math state tests in grades 4-8—to every teacher in a school or district, regardless of the subject or grade level a teacher teaches. For instance, since a sixth grade social studies teacher does not have a state test that produces value added results, her student growth score would be based on how her students performed on their reading and math tests. Under Mohip’s plan, each teacher would be held accountable for the entire district’s progress—meaning that the aforementioned sixth grade social studies teacher wouldn’t just be evaluated based on her sixth grade students’ ELA and math scores, but on the value added scores of every student in the entire district.

This is nuts.

In theory, I suppose, shared attribution could inspire a collective, “we’re all in this together” culture. Unfortunately, that’s unlikely to happen. Despite what the word “shared” implies, shared attribution doesn’t actually ensure that teachers share accountability—just that core teachers with value added data are responsible for the evaluation scores of non-core teachers (like gym, art, and music) in addition to their own. Statewide, the number of teachers who can actually be evaluated based on value added measures is small: only 20 percent of Ohio teachers are able to be measured using the state assessment either in whole or in part.[1] If that percentage holds in Youngstown, that means the majority of Youngstown teachers will have no significant influence over half of their final evaluation rating.

Evaluating anyone, including teachers, on results they can’t directly influence is unfair. So why force it onto an entire district? Mohip asserts that it will help “motivate teachers to help students in areas in which they need the most support—even if that’s not their subject.” But the logic behind this statement is faulty at best and ignorant at worst. For starters, it elevates reading and math above all other subjects. While no one would argue that learning to read and do math is not a vital part of a student’s education, so too is the content learned in science, social studies, and other classes. Recent reports and studies of other states have shown that adopting a high-quality, content-rich curriculum may be the best step toward improving reading and math achievement—arguably far better than expecting non-core teachers to teach content they aren’t experts in. Mohip would be better off focusing on what teachers are teaching and how they are teaching it rather than trying to force art and gym teachers to teach reading strategies.

But a narrowed curriculum isn’t the only negative consequence of this new evaluation system. Historically, teacher evaluations have aimed to accomplish two goals: holding teachers accountable for their performance and helping them get better through feedback. Mohip mentioned both of these aspects when unveiling his new system—he noted that he wants to provide teachers with more “feedback that’s going to be able to help [them] become a better teacher” and that the system is about “holding everyone accountable.”

But the new system does neither of these things. District-wide shared attribution risks inflating or deflating the overall evaluation score of teachers depending on whether the district does well on value added. Half of all teachers’ score will be exactly the same—which could potentially hide meaningful differences between teachers.

As for professional development: The feedback teachers receive will come from classroom observations, not from student growth measures. Unfortunately, other than a vague reference to creating the “professional development path every teacher needs,” there’s no clear indication of how the district plans to improve the feedback that teachers previously received under the state evaluation system. This is particularly problematic considering that the state’s rubric and template for professional growth plans are woefully insufficient. The Educator Standards Board recently made some solid recommendations for how to improve the rubric, but those recommendations are virtually useless to Mohip and his staff, since they suggest incorporating content-specific student growth measures into the rubric and getting rid of shared attribution altogether.

Most folks would agree that Youngstown’s long history of poor academic performance is more than enough reason for Mohip to incorporate some drastic policy changes. As CEO, he is certainly entitled by law to do so. But great power also brings great responsibility, and Mohip’s chief responsibility is to improve the education provided to the thousands of students in his district. Plenty of research has shown that quality teaching is necessary for students’ achievement and positive labor market outcomes, so Mohip is right to focus on teacher accountability and improvement. But he’s wrong to assume that shared attribution is the best way to accomplish these goals. Not only will it fail to effectively and fairly differentiate teachers, it will also lead to a narrow focus on reading and math at the expense of other subjects—a move that the students in Youngstown just can’t afford.

[1] The 20 percent is made up of teachers whose scores are fully made up of value added measures (6 percent) and teachers whose scores are partially made up of value added measures (14 percent).

- We’re back after a little break on Friday, with a lot of central Ohio education news. Stay with me on this first one; it’s twisty. Twenty-some years ago, Columbus City Schools was embroiled in a lawsuit over the use of religious music—specifically Christian hymns and spirituals—used in its graduation ceremonies. To end the suit, the board agreed to implement a no-religious-music policy district wide. Well, somehow that policy disappeared from the district’s rulebook a couple of years back and its absence was noted last week. Some board members are trying to get it reinstated, some are wondering if it can be finessed, and still others are more concerned about how it disappeared in the first place and wondering whether the policy was violated while it was accidentally off the books. (Columbus Dispatch, 11/9/17) Some of the original parties to the 90s-era lawsuit are still around and are of course adamant that the no-religious-music policy be reinstated immediately. The ACLU is intrigued as well, and would additionally like to know how the policy got dropped in the first place. I think the word they’re looking for is “boilerplate”. (Columbus Dispatch, 11/10/17)

- The urban development guru at Columbus Underground reported last week that Columbus City Schools will be auctioning off more surplus properties at the end of the month, including a couple in prime hipster locations. Hopefully these will be actual auctions rather than end-run sales to predetermined “state entity” buyers so that the district can maximize its return on the assets. Yes, even if they have to sell to one of those pesky charter schools. (Columbus Underground, 11/10/17)

- Finally, the Columbus school board was somewhat divided last week on the issue of whether they should require their new superintendent to live in the district. Current supe Dan Good does not and has never done so, and some folks worried that such a requirement would cause some potential candidates to avoid applying for the job (whyever would that be?). In the end, they agreed that “the successful candidate is expected to live in the district”. And you know what they say about high expectations in school. (Columbus Dispatch, 11/10/17)

- I have always thought it would be an interesting research project to compare big urban school districts to one or more of their inner-ring suburban districts. Places where the demographics are very similar but the footprints much different. Can a smaller version of an urban district do better in dealing with “big city problems”? Are they more nimble or adaptable? Or are they similarly struggling? One such comparison here in central Ohio is Columbus City Schools and neighboring Whitehall City Schools. The Dispatch is today looking at a resurgence of the old and tiny ‘burb, including both economic and educational dimensions. There’s not a ton of data yet, it seems, but those pesky charter schools are “stealing” fewer kids so there’s that. (Columbus Dispatch, 11/13/17)

- And speaking of small Ohio school districts getting attention, a national podcast series recently took a look at Steubenville schools in remote Eastern Ohio. This time, actual (and impressive) data is involved! As you may recall, Steubenville stood out as one of the few districts to achieve As in both growth and proficiency scores on its most recent state report card. It is specifically important because Steubenville is a quintessential post-industrial Rustbelt town that has experienced every piece of bad fortune you think of associated with that description. How have they managed this feat? Take a listen to get a better sense. (EdTrust Extraordinary Districts podcast, November, 2017)

- Still riffing off of the Council of Great City Schools conference held in Cleveland last month, Patrick O’Donnell has this preview of a bill coming down the pike in the Ohio General Assembly which aims to ban out-of-school suspensions for students in third grade and below. I'm going to go out on a limb and guess that I can count Senator O’Donnell as a Yes vote. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 11/12/17)

Massachusetts produces the best educational outcomes in the country. Its reading and math scores have long topped the National Assessment of Educational Progress. It’s the only U.S. state that competes with the planet’s strongest-achieving countries on international tests. And it’s the first U.S. state in which a majority of the workforce holds a four-year degree.

Massachusetts’s results weren’t always this strong, however. Its ascent began in the 1990s with a series of reforms that transformed its K–12 education system.

The House Republican tax reform plan, contained in its proposed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, includes a provision to expand the Internal Revenue Code section 529 savings plans to include expenses for kindergarten-through-grade-twelve education and apprenticeship programs. The maximum annual amount of such expenses allowed from these plans would be $10,000.

Supporters of educational choice should embrace this proposal and advocate for its inclusion in the final, adopted tax bill. Simply put, expanding 529 college savings plans for K–12 education and apprenticeship programs will enable more families to access educational choice before their children enroll in college.

Current tax law restricts 529 savings plans to higher education and allows maximum annual contributions of up to $5,000 per year for each individual account ($10,000 for joint-income tax filers).

While contributions to existing 529 college savings plans are not deductible for federal income tax purposes, the accrued interest is not subject to federal tax.

In the process of proposing to expand the 529 plans to K–12 education and apprenticeship programs, the House GOP tax plan would eliminate Coverdell Education Savings Accounts, which is the current savings vehicle for K–12 expenses for up to $2,000 annually, since they would be duplicative.

As a practical matter, the House plan would effectively expand, by five times, the Coverdell account annual expense limits by replacing them with 529 savings plan accounts for K–12. That’s a good thing.

When Congress authorized the existing 529 college savings program in the 1990s, Republicans and Democrats agreed: Helping families at every income level save for their children’s college was good public policy.

If tax incentives to help families save for college costs makes sense—and it does—the same can and should be said for K–12 education and apprenticeship expenses.

If, for example, a working- or middle-class family invests $2,500 annually from the child’s birth in a 529 plan to save for entry to middle school, the federal tax-free savings alone would amount to nearly $8,000, almost a full year’s tuition at a Catholic high school. (This is based on the historic average annual growth in the S&P 500 of 9.8 percent.) Importantly, this savings at the federal income tax level does not include likely state income tax savings that also would result from expanded 529 plans.

Expanding 529s is something Congress and the Trump administration support. At the very least, they should ensure its inclusion in the final bill.

Several school choice advocates have found reason to criticize the 529 expansion proposal. This is shortsighted, and makes the perfect the enemy of the good.

Some advocates—and non-supporters of school choice—for example, argue that 529 plans primarily benefit the most affluent households. Despite claims by the New York Times, only a very small percentage of millionaires bother to use the 529 savings accounts for college, approximately 0.5 percent of 529 owners, according to an analysis done by Strategic Insight. That’s for the obvious reason that a capped maximum annual donation amount means that 529s are worth proportionately less to a wealthy person.

In fact, according to that same analysis, more than three-quarters (77.2 percent) of the families with 529 plans made less than $150,000. In dozens of high-cost metropolitan areas of the country, this income-level ceiling constitutes a middle-class, not wealthy, lifestyle.

Moreover, 529 savings plans for college have become more popular both in terms of numbers of families that own one and the dollar amounts being saved. According to Strategic Insight, from 2010 through June 2017, the number of 529 accounts increased from 10.1 million to 13.1 million, with assets increasing from $167 billion to $300 billion.

The reality of the moment is that none of the Trump administration’s modest school voucher and charter proposals survived the congressional budget process this year, as Republican-controlled committees rejected them.

Making the House proposal on 529 savings plans a reality for American families certainly need not cease efforts to bring school choice through other means to even more families. Rather, it should accelerate such efforts.

With expansion of 529 plans on the tax reform table, the focus for school choice advocates should be to make sure this proposal gets passed, which would be an important step forward for educational opportunity.

Peter Murphy is Vice President for Policy at the Invest in Education Foundation.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

School choice has long been the centerpiece of President Trump’s education policy platform. On the campaign trail, Trump promised $20 billion in federal funds to expand school choice. He reiterated this promise in his address to Congress last winter, calling on the legislature to pass a bill “that funds school choice for disadvantaged youth.” Now, with tax reform on Congress’s calendar for the rest of the year, the president has the perfect opportunity to deliver on those promises: a big investment to help poor families by expanding school choice.

Unfortunately, the main provision in the GOP tax reform bill concerning K–12 education falls well short of the administration’s stated goals.

This provision would allow families to use tax-advantaged 529 college savings plans for K–12 educational expenses, such as private school tuition. Under a 529 plan, a family can deposit after-tax dollars into a savings account on behalf of a child or other designated beneficiary. The initial contributions accrue earnings over time, and families pay no taxes on those earnings so long as they are used for educational purposes. Republicans argue this would advance school choice at the K–12 level.

529 plans are well-suited to pay for college expenses, since earnings can accrue for decades and offer families a large tax benefit. But this same feature makes them ill-suited for K–12 expenses, which families face much sooner. A simple hypothetical illustrates how using 529 benefits for K–12 expenses results in a smaller net benefit from the government to students.

Consider a family who deposits $250 monthly into a child’s 529 account solely for college expenses. The parents start saving when their child is born and realize an annual return on their contributions of 5 percent. With such disciplined savers as parents, the student’s 529 would yield $20,000 for all four years of college, with nearly $35,000 left over for graduate school. The 529 plan provides an effective 6.9 percent college tuition subsidy. Adding in graduate school, the total present value of the 529 plan’s benefits is $8,030.

Now consider what happens if the student’s 529 is used for high school tuition beginning in ninth grade. At $10,000 per year for four years of high school, the 529 account still yields $20,000 for two years of college, with $18,279 remaining for a third year. Under this scenario, the benefit is worth $6,031, providing a total subsidy of 5.0 percent. By withdrawing the 529 funds early, this family has reduced its federal benefits by a quarter.

Withdrawing funds earlier yields even smaller benefits. If our family starts paying private school tuition in elementary school (again at $10,000 per year), the money would run out by fourth grade, yielding federal tax benefits of only $1,392. Increasing contributions won’t fix the problem, as another $100 a month would only stretch the money to sixth grade, yielding $2,363 in benefits.

To be sure, 529 plans may offer a larger windfall when factoring in benefits at the state level. Families residing in one of the 33 states allowing state tax deductions or credits for 529 contributions would get larger benefits. But since state income tax rates are much lower than federal rates, the savings from even the most generous state policies are limited. Moreover, the whole point of President Trump’s campaign promises was to increase financial support for school choice at the federal level.

The central problem with using 529 plans in elementary or high school is that the benefit stems from compound interest, which only accumulates appreciably over time. Under the ideal scenarios above, the moderate college subsidy is drastically reduced when funds are withdrawn for earlier schooling. Of course, average savers don’t start so early and are apt to get less than ideal amounts. For instance, families who start saving when their child turns three realize benefits of $5,278 if they use the funds for college. Using the funds for high school reduces that benefit to $3,621, while using them for elementary school makes it $542.

Delivering on the Trump administration’s school choice promises would require substantial investment from the federal government, targeting benefits to the disadvantaged, and expanding school choice. But Congress’ proposed expansion of 529 plans does none of this.

Under the GOP plan, most parents who use their 529 plans for K–12 education rather than college expenses would actually derive less of a benefit from the federal government. Even families who increase their contributions are unlikely to enjoy net significant additional savings. Expanding 529 plans would cost the federal government just $600 million over 10 years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. So much for a $20 billion federal investment in school choice.

The scenarios outlined above require families to chip in $3,000 per year—well beyond what most poor families’ are able to save. As currently structured, 529 plans are not designed to deliver significant benefits to poor families in college. Giving families flexibility to spend those funds sooner does nothing to address their capacity to save; it only minimizes the potential benefits.

Allowing families to use 529 plans for K–12 education won’t expand school choice. The benefits are too marginal to provide many families with new options. The parents who will benefit most from these changes are those who already send their children to private schools or have access to tax advisors to help them plan their savings. If Congress really wishes to advance the administration’s stated goals on school choice, it would do better to scrap these reforms to 529 plans and come up with a different proposal.

Nat Malkus is a resident scholar and the deputy director of education policy at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where Preston Cooper is an education data analyst.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the authors and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearPolicy.