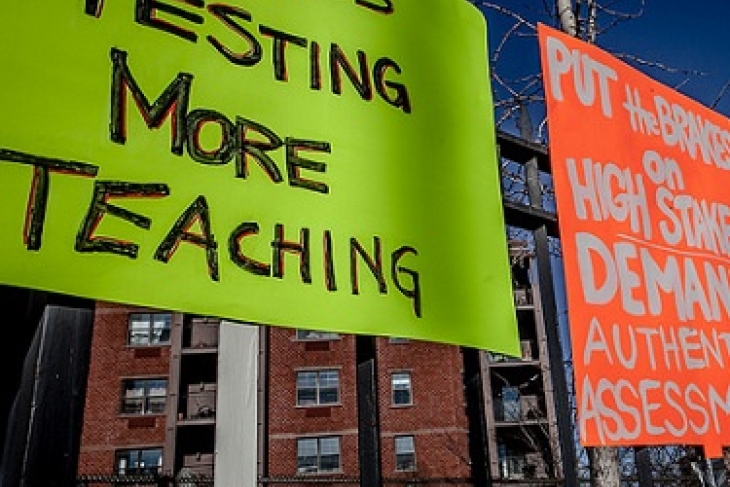

The testing “opt-out” movement is testing education reform’s humility.

The number of students not participating in state assessments is large and growing. In one New York district, 70 percent of students opted out; in one New Jersey district, it was 40 percent.

Some reporting makes the case that this phenomenon is part of a larger anti-accountability, anti-Common Core story. Some reformers, it seems to me, believe opting out is the result of ignorance or worse.

Participants are routinely cast as uninformed or irrational. Amanda Ripley implied that opting out of testing is like opting out of vaccines and lice checks. New York Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl Tisch argued, “We don’t refuse to go to the doctor for an annual check-up…we should not refuse to take the test.” A column in the Orlando Sentinel argued we’d “lost our minds” and that the “opt-out movement has officially jumped the shark.”

Such condescension is eerily similar to the most regrettable things said about Common Core opponents: Their resistance was a “circus,” just “political,” and “not about education;” opponents must be “comfortable with mediocrity,” “paranoid,” and/or “resistant to change.”

I’m not defending every charge ever made against testing or Common Core. For sure, some of the oppositional rhetoric was overheated or out of bounds. And there have certainly been advocates, like Mike Petrilli, who argued the case on the merits.

But I’m concerned that education reform’s propensity for pride may have taken an even more unforunate turn with opt-out. One emerging narrative is that we should be suspicious when certain groups of people question our policy preferences.

The first sign was Secretary Duncan’s infamous reference to the opposition of Common Core from “white suburban moms.” More recently, Robert Pondiscio noted that opting out (like craft beers, NPR, and farmers’ markets) could be placed on the “Stuff White People Like” list.

Most provocatively, Chris Stewart wrote a piece titled “Painting education the whitest shade of pale.” It argued, “Renewed resistance to accountability is now a middle-class project to ‘reclaim’ schools for a select slice of the American population who no longer want teachers and schools to be on the hook for results or equity.”

Taking issue with the AFT’s involvement in opt-out, Stewart wrote, “Why waste an opportunity to exploit the energy of white moms and the teachers that serve them who now see the obsession with closing racial disparities in schools as stealing joy from children of relative privilege?”

I don’t want to infer too much about these individuals’ intentions. But I’m worried that such statements, when taken together, give the impression that education reform believes that the opinions of white or middle-class families should be viewed with skepticism or antipathy.

Non-poor, non-minority families love their kids and have every right to participate in the public debate about public education. I’m a strong supporter of assessments and accountability, and I wouldn’t opt out. But I think it’s unfair to discount the views of those who disagree, and it would be untoward to suggest they don’t care about other kids or are insensitive to issues of race and income.

My reading of the situation is that a significant number of American families have misgivings about what’s happening in their public schools. Most of the issues about which they have concerns—whether it’s standards, assessments, teacher evaluation, or something else—are policies developed at the state or federal level.

Had these policies been created locally, families could petition their local school boards for redress. But now, unable to change decisions made by faraway state and federal policymakers, these families are employing a kind of civil disobedience. They are using the power they do have—to decline participation in state tests—to demonstrate their frustration with the status quo.

We could disparage them. But that would only serve to insult and incite.

Or we could humbly listen, respectfully argue our case, and make the necessary course corrections.

Fortunately, there are examples of this already taking place. Secretary Duncan has encouraged states to reduce the number of tests. Some states have created task forces to study assessments. An Education Post piece recognizes the case made by opponents but also encourages them to recognize the value of accountability. Pondiscio has suggested a way for opt-out families to bring about constructive change. Rick Hess has encouraged reformers to appreciate the fact that many parents believe “tests and the accountability systems linked to them are not good for their kids.”

In my opinion, education reform’s response to the Common Core backlash was hubristic. Opt-out gives us the chance to either learn from that mistake or repeat it.