During a January 29 town hall in Washington to discuss dismal new test results, Harvard professor Marty West—who serves as the vice chair of the board that oversees national testing—poked his finger straight into the light socket.

Asked by NPR correspondent Cory Turner why student performance plateaued in the 2010s and then began to decline, West referenced a term that is less popular in education circles than head lice: “There is good evidence, some of which uses NAEP data, that really does suggest a lot of that progress in the 1990s and 2000s was driven by test-based accountability.”

Accountability? Test-based accountability?

Surely, he misspoke.

Everyone hates accountability. Embodied by the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) passed in 2001, it was associated with annual testing in grades 3–8 and demands for constant improvement of results—particularly among struggling subgroups.

Critics saw accountability as a counterproductive fiasco that degraded education without delivering the performance miracles it promised. Instead, they argued, it encouraged states to set low standards that students could easily meet, focus excessive attention on students near the cusp of passing, cheat to avoid punishment, narrow the curriculum to reading and math, and scrap real instruction in favor of endless test prep.

Sounds miserable, doesn’t it? In 2015, Congress acceded to the critics by scrapping NCLB. States would henceforth develop their own systems for accountability with relatively few guardrails.

And yet here we’ve got Marty West, uttering the A-word in public. They didn’t even bleep it on the broadcast.

He isn’t the only one. I’ve heard the A-word more times in the past month than in the past five years. It’s suddenly back. To understand why, we need to rewind a bit.

What happened after NCLB?

State systems for school oversight post-2015 were “accountability” like Scooby Doo was a guard dog.

In the absence of a muscular state or federal role, we entered a new era that put the onus on parents. It was unspoken. No one issued a decree that said parents would henceforth be on their own to ensure schools delivered on their promises. That’s just how it worked in practice. Parents had to fill any gaps that arose. It was parent accountability.

Privileged students did fine under this approach. Their parents tended to have college degrees, higher incomes, and discretionary time to engage. These families monitored their kids progress constantly, alert to any sign of struggle by the child or low expectations from teachers. They pushed their kids into advanced coursework. They limited screen time at home and ensured homework got done. They paid out of pocket for extra tutoring when it was necessary.

Less privileged students did not do fine. Their performance dropped noticeably before the pandemic and catastrophically during it. Perhaps their parents assumed everything was OK unless someone told them otherwise. As grade inflation increased, families likely heard only rosy messages.[1] There’s reason to suspect that devices meant for completing schoolwork were repurposed for surfing the web and social media. We know that absenteeism went through the roof.

Now’s a good time to mention a trend that has been overlooked in the coverage of our recent NAEP results. It’s been widely noted that very-high-performing students—say, those at the 90th percentile of the performance distribution—are holding steady or improving, while very low performers—those at the 10th percentile—are declining steeply.

This is true. But even among high performers, gaps have widened between students along socioeconomic lines.

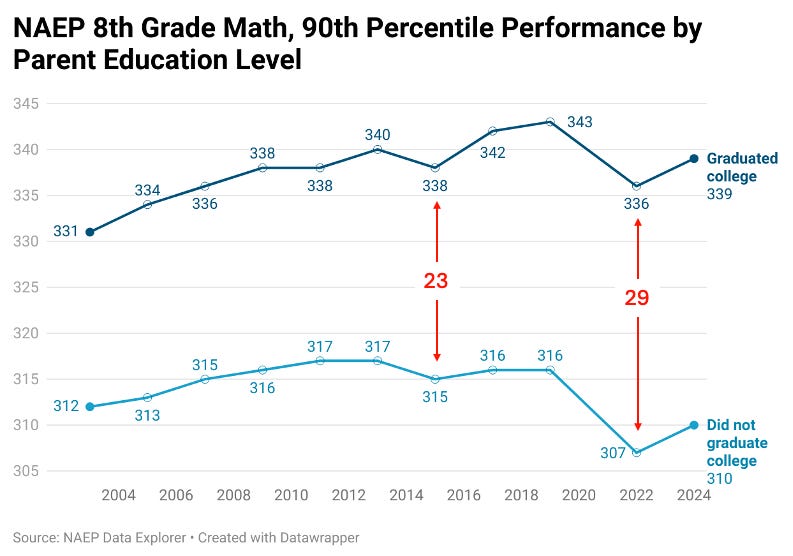

Consider the chart below. It maps 8th grade math scores for students at the 90th percentile from 2003 to 2024. The top line shows children of college graduates. The bottom line shows children whose parents had less than a college diploma—meaning they did not graduate high school, received only a high school diploma, or completed only some college.

The lines mostly move in tandem until 2015, when the gap was 23 points. Beginning in 2017, high performers from lower education households stopped improving even as their counterparts from more-educated households still climbed. Those whose parents did not graduate college also had a larger drop during the pandemic. Between 2015 and 2022, the gap between these groups grew by 6 points, which is more than half a year of learning.

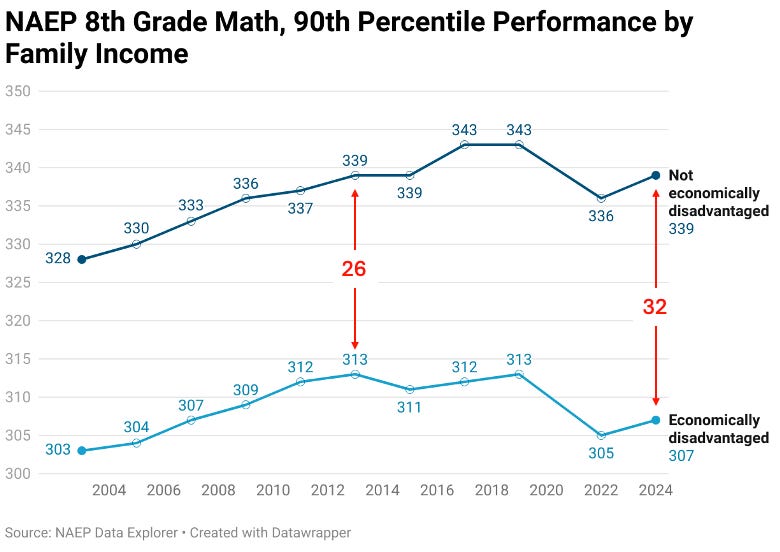

If we look at the same group—high performers—broken out by household income, we see a similar pattern. After 2013, lower income students stalled while their higher income peers improved. Gaps got larger.

If this is what happened among strong students, you can imagine what happened to strugglers. It was much, much worse.

Education has always had a significant inherited dimension, where those who thrive in school tend to have children who do well, too. Genes matter, two-parent households matter, etc. Poverty, neighborhood violence, and trauma suppress achievement for less privileged kids. But in the past decade, the power of these factors has been magnified. Instead of increasing opportunity by allowing children of all backgrounds to maximize their potential, our system is conferring advantages on the students who already have the most of them.

That’s what accountability is meant to address. It forces us to pull apart averages so we can see the underlying patterns and adapt when we’re replicating unfortunate legacies instead of breaking them.

Wider trends are renewing interest in accountability

Here are three key reasons that chatter about accountability is humming:

-

Satisfaction with US public schools hasn’t been this low since the Millennium. According to a recent Gallup poll, education ranked twenty-ninth out of thirty-one aspects of society, just below “the amount Americans pay in federal taxes” and “the size and influence of major corporations.” Guess what happened the last time education did this poorly in the poll? Congress passed NCLB.

-

Schools are making weird decisions. More districts, for example, are adopting a four-day school week. Given what happened when students had less school during Covid, you are probably unsurprised that a shorter week generally hurts learning. Districts tend to justify it by claiming it saves money (the amounts are trivial) or helps them retain teachers (it doesn’t). But they keep doing it. Some of them are also limiting access to advanced math or purchasing vibes-based reading curricula. All dubious strategies for delivering results.

-

Spending has increased. Achievement has not. In 2024, the Census Bureau reported the largest spike in per pupil funding in over twenty years. Meanwhile, student performance has dropped to levels not seen since the 1990s or before. State-by-state analysis from the Edunomics Lab will shock you. The cost-benefit relationship is off.

What would next-gen accountability look like?

We now understand why Professor West was dropping the A-bomb.

But there’s little reason to believe there will be a return to NCLB-style, federal accountability anytime soon. The Trump administration quite famously wishes to abolish the Department of Education. NCLB was unpopular even during its prime. Republican state leaders are focused on expanding education savings accounts (ESAs), not regulating schools. Democrats have given up on K–12 education almost altogether.

And still, folks keep saying “accountability.” What do they mean? Here are my guesses:

-

Establish student learning as the non-negotiable responsibility of schools. Schools should have clear, public goals for achievement on state tests that are set in advance and reported out in a timely way. Tests aren’t the whole ballgame, but outcomes on tests absolutely matter. Without goals, schools spin any and all results as wins by cherry-picking whatever’s positive. They just did that with NAEP. Additionally, schools have been pressured to take on functions that are not their core competency, like providing mental health services and fighting culture wars, which make it more difficult to deliver on academics. Learning comes first. That’s what the public wants.

-

Distinguish between success and failure. I’ll pick on California here for a second. Back in 2017, freed from its NCLB constraints, California unveiled a new school rating system. The Los Angeles Times said it “grades on a curve and paints a far rosier picture in academics than past measurements” and “nearly 80 percent of schools serving grades three through eight are ranked as medium- to high-performing.” Instead of ratings with actual names, the new system used colors. It hasn’t gotten better. Last September, California was assigned a D-grade by the The Center on Reinventing Public Education for obscuring information about student performance on its dashboard. It feels sometimes like the state prides itself on not knowing the difference between good and bad schools. If states aren’t going to hold schools accountable, the least they can do is empower families and communities with clear, actionable information to do it locally. Compare each school’s results with those that are demographically similar and be transparent about which ones are doing the best. Many states could do better in this regard.

-

Reward smart spending. Chad Aldeman recently showed that our public schools added 121,000 employees last year. Is that because there were more students? Nope. Enrollment actually dropped by 110,000 kids. For every student we lost, we hired approximately one new staff member. That’s wholly unaffordable. I have some sympathy for schools here. They were sent dump trucks of money and a limited time to spend it toward Covid recovery. They did their best, though the hiring pool for educators was far from ideal. But it’s time for a reset. Taxpayers cannot continue to increase school budgets at the past decade’s pace. With enrollment forecasts down, we’re headed for belt-tightening. We should be offering financial incentives to districts that get more efficient by developing new staffing models, using technology smartly, and intervening with students early to avoid costly catch-up later. None of that is happening now. Accountable spending means looking not only at results but how much it costs to get those results.

This is how we end the education depression

In October, I argued that we’re stuck in a depression that began around 2013 and has now lasted more than a decade. In a subsequent post, I suggested that our strategy must encompass birth to age twenty-five so we are measuring our school systems based on the adults they produce, not just short term proxies.

Widening our aperture is critical. But we still must assess our performance and make decisions year-to-year. We need accountability. If state and federal officials don’t step up—and right now, it does not look like they will—nothing’s stopping educators and families from working together to do this locally. Local school boards can lead the effort. It’s the best way to support our students and the best way to earn future investments in our schools. Stop waiting for the higher ups to play the heavy.

Otherwise, school budgets are going to become tantalizing targets for cuts. Too many unneeded buildings, too many staff, uncontrolled pension obligations—all in the shadow of enrollment losses and underwhelming achievement.

If we fail to act and public support for schools dries up, we’ll be using stronger language than the A-word.

Editor’s note: This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

[1] Mississippi is a notable outlier here. Part of its literacy overhaul—which led to it zooming up the national rankings—required schools to communicate with parents when students are struggling with reading. In this era that pushed more onus on parents, Mississippi also ensured they knew then their children needed help. It’s also true that Mississippi ramped up its statewide push in the 2010s when most states were throttling down education reforms.