Poland has been the economic tiger of Europe in recent decades and one of the fastest growing economies in the world over that time. In 1990, when I taught high school in a rural Polish town located in Silesia between Poznan and Wroclaw, Poland’s GDP was less than Ukraine’s. As noted recently by the journalist Anna Gromada, at the fall of the Berlin Wall in late 1989 “the 13:1 per capita gap between Poland and soon-to-be united Germany was twice that between the U.S. and Mexico.”

Between 1990 and 2018, however, Poland’s GDP increased almost eightfold. The Business Leader reported in late May that “the GDP per capita has already surpassed those of Portugal and is on track to beat the Italian (late-2020s) and even French levels (early-2030s).” And the Centre for Economics and Business Research predicts that Poland’s Gross National Income per capita will surpass that of the United Kingdom by 2030.

Many factors lie behind Poland’s impressive economic growth and its emergence as a “global power.” These include its embrace of economic freedom and innovation, robust infrastructure investment, access to European Union markets and investments, really hard-working citizens, and education. The power of education is most interesting to me, going back to when I taught there and saw the Polish commitment to it first-hand.

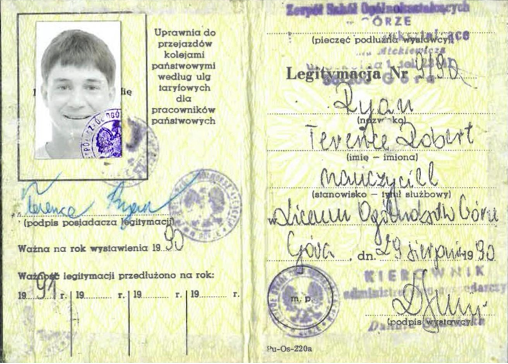

Polish teacher credentials from 1990–91 for the author.

Mateusz Urban, Senior Economist at Oxford Economics, argues that Poland’s “focus on education and skills development has helped them cultivate a talented workforce, which is a crucial asset in today’s competitive global landscape and I think crucial to their rise as a European powerhouse.”

Over the last thirty-four years, I have visited many times with my Polish wife and our two daughters. In May, we spent three weeks traveling across the country and saw first-hand the ongoing power of education to improve individual lives and a nation’s overall well-being. My wife’s family is large. She has seventeen nieces and nephews, and we met almost all of them and their families. They are the beneficiaries of Poland’s economic growth and educational opportunities.

Most of the next generation speak some English, and a few are completely fluent. They work hard across a variety of professions, including teaching (English!), banking, science, engineering, and trucking. They own homes and travel across Europe. One nephew speaks multiple languages and is completing his bachelor’s degree with honors in Wales. What’s remarkable is that my wife, one of seven children, educated during the Soviet period, is the only one of her siblings that attended college and speaks English.

The story of my wife’s family is very much the modern tale of Poland. Journalist Anna Gromada captured this when she observed, “Since 1989 my family has gone from farm laborers to high achievers.” We saw this transformation when we visited Krakow, founded in 1257 and on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Cities.

Yes, Krakow swarms with tourists who spend freely. But, according to the Warsaw Business Journal, “Krakow’s primary assets are its people, namely its well-educated workforce and professionals, which is largely what attracts businesses and investors. Multinational corporations choose Krakow not because it is cheaper, but because of the value of what it offers.”

But education in Poland is not only about creating a dynamic workforce for a world-class economy. Even more important, education is about helping the next generation understand what it means to be a Polish citizen and the responsibilities that come with it. During our travels, we visited historical sites in Gdansk, Warsaw, and Krakow (as well as lesser-known towns like Hel on the Baltic Sea and Zakopane in the Tatra Mountains).

At all these places, we saw school children in their yellow hats or blue t-shirts visiting historical sites with their teachers and local historians and experts. We listened in to conversations between adults and students in places like the Warsaw Uprising Museum, the Museum of Warsaw, and the Jagiellonian University (founded in 1384 and attended by the likes of Nicolaus Copernicus, Pope John Paul II, and Nobel Prize Winning poet Wislawa Szymborski).

Polish students in Krakow.

Poland has had to fight for its existence over the centuries. As it grows into a dynamic Twenty-first-century power, it lies on the free world’s outer edge. It has a 142-mile border with autocratic and hostile Russia in the north, and to the east, it borders Russia’s ally Belarus and war-torn Ukraine. Much of the Western support flowing to Ukraine flows through Poland. Not surprisingly, according to the Warsaw Business Journal, “83 percent of Poles believe that the war in Ukraine poses a threat to Poland’s security.”

The Polish education system is responding to this threat. The BBC reported on June 3 that, “In a school just outside Warsaw, children have been learning survival skills. It’s part of a new program that’s sending soldiers from the Territorial Defense to teach emergency drills in classrooms across the country.”

In 1990, as I struggled to teach English to my Polish students, we would periodically hear the Russian jets based nearby fly over our school. They’d break the sound barrier to rattle our windows and classrooms and maybe our nerves. But we all knew the Russians were in retreat. Fast forward thirty-four years and Poland is a powerful country that is a beacon for what Ukraine wants—freedom, economic opportunity, and better lives for their children. It is also what Russia despises and fears. Education matters, and Poland proves it.