For the past decade, Washington, D.C., schools have shone as a success story, with achievement for all students rising steadily in elementary and middle schools and more quickly than the national average. But several years’ worth of that growth has been wiped out by the Covid-19 learning slide, and racial disparities in achievement have widened dramatically, a new analysis by my non-profit research organization, EmpowerK12, has found.

In analyzing three different types of assessments for nearly 20,000 D.C. students in both traditional public schools and charters, we have assembled one of the most complete pictures yet produced of the pandemic’s impact on urban education.

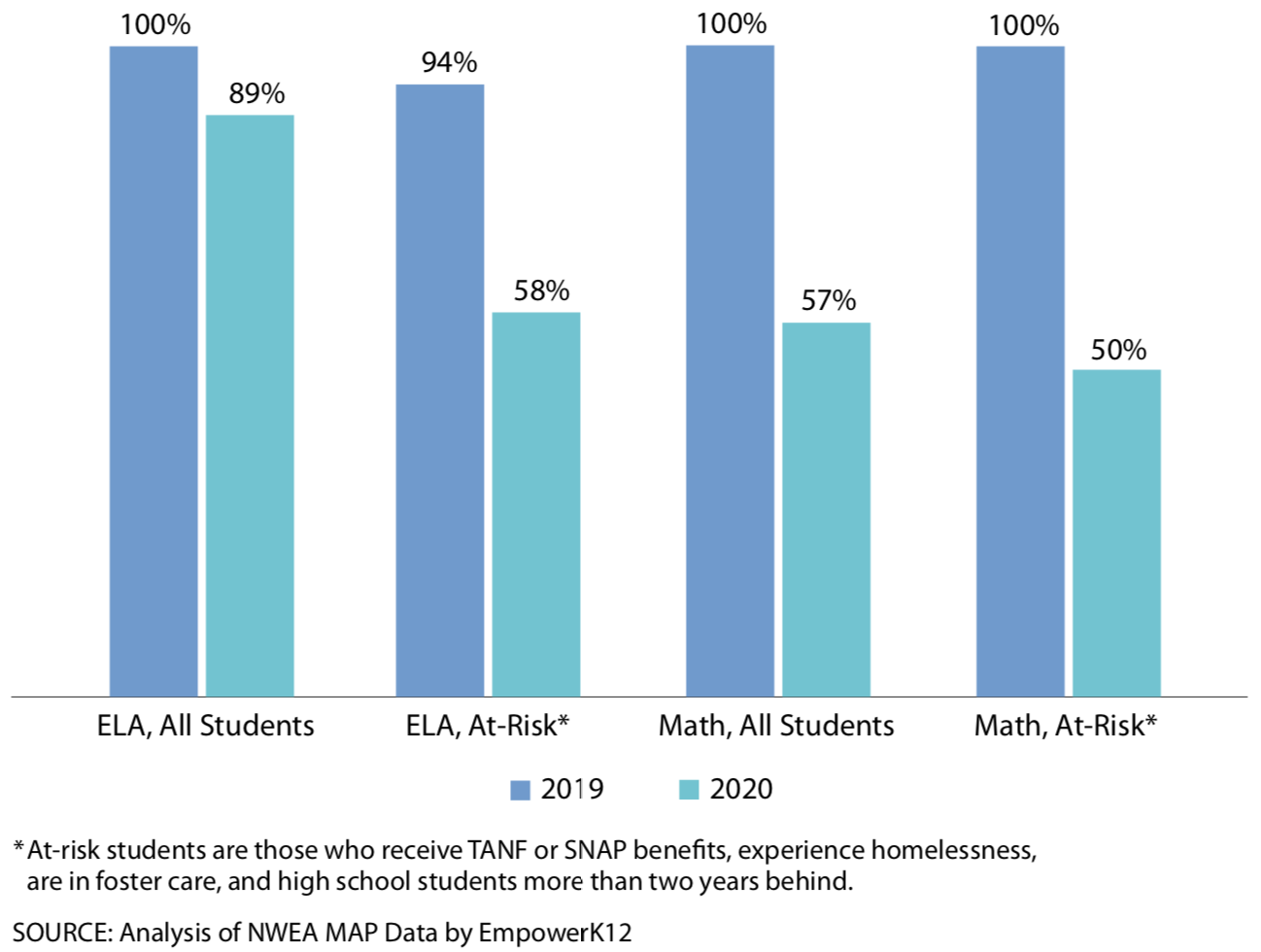

Figure 1. Percentage of D.C. students achieving expected annual growth in math and reading, grades three through eight

As in many cities, the impact of the Covid slide in D.C. is most severe for students who are identified as at-risk, those who receive TANF or SNAP benefits, experience homelessness, are in foster care, and high school students who are more than two years behind. While the city’s students on average have lost four months of learning in math and one month in English language arts during the pandemic, at-risk students, who make up 47 percent of Washington’s public-school students, lost five months of learning in math and four months of learning in English language arts.

The picture is very different for more affluent students and White students. All D.C. students have suffered losses in math during the pandemic. Yet students who are not considered at-risk produced 14 percent more growth in reading than expected on the MAP and i-Ready assessments used in the nation’s capital. While Black students produced 38 percent less than expected growth on the tests, White students gained 76 percent more than expected.

Not surprisingly, students in the city’s poorest neighborhoods suffered the greatest learning loss. Schools east to the Anacostia River, serving many of Washington’s most disadvantaged communities, fell 51 percent below their expected growth rate on the MAP and i-Ready tests, while those in schools west of the river were 10 percent above expectations. All of D.C.’s traditional public schools and most charters provided distance learning during this period. We have no data showing the differences among students learning in-person or virtually at this point.

The pandemic has also undermined the progress of Washington’s youngest students in reading, a key building block of both the city’s school reform effort and student success.

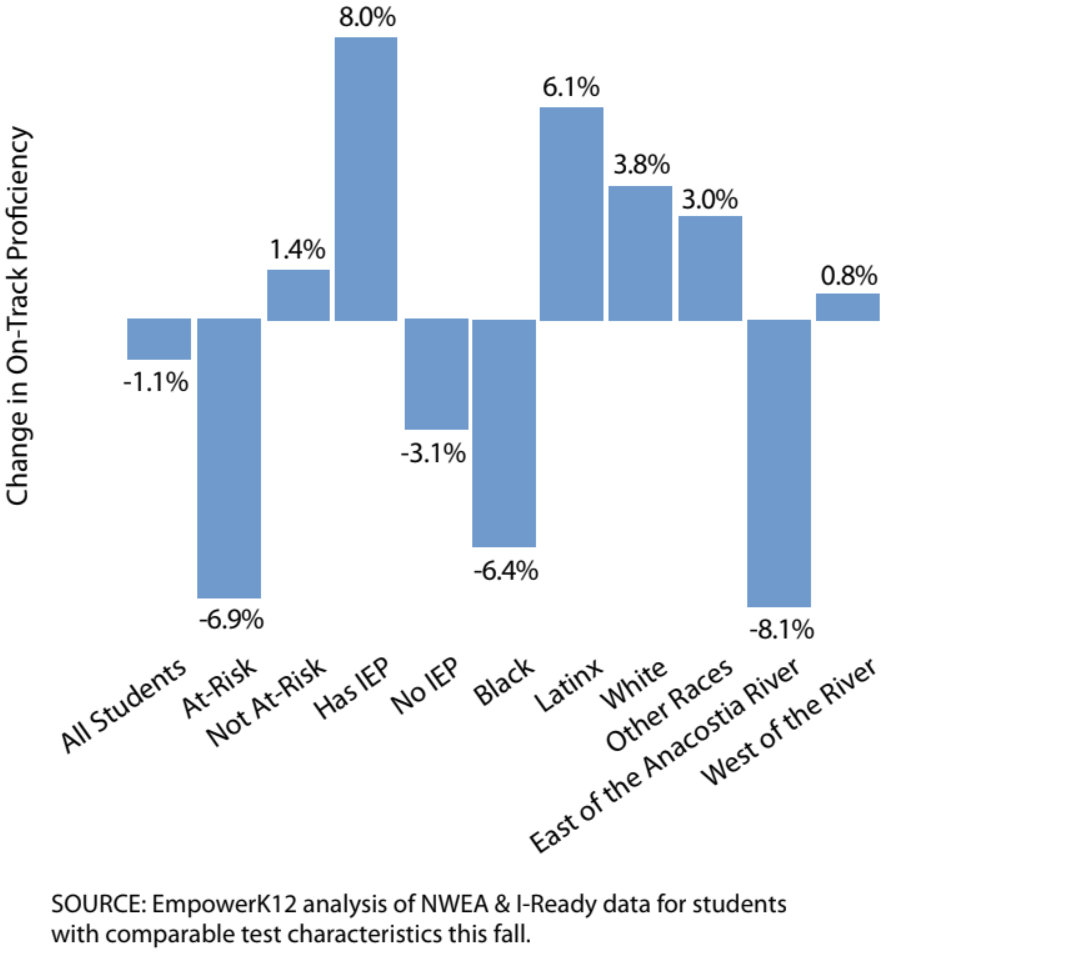

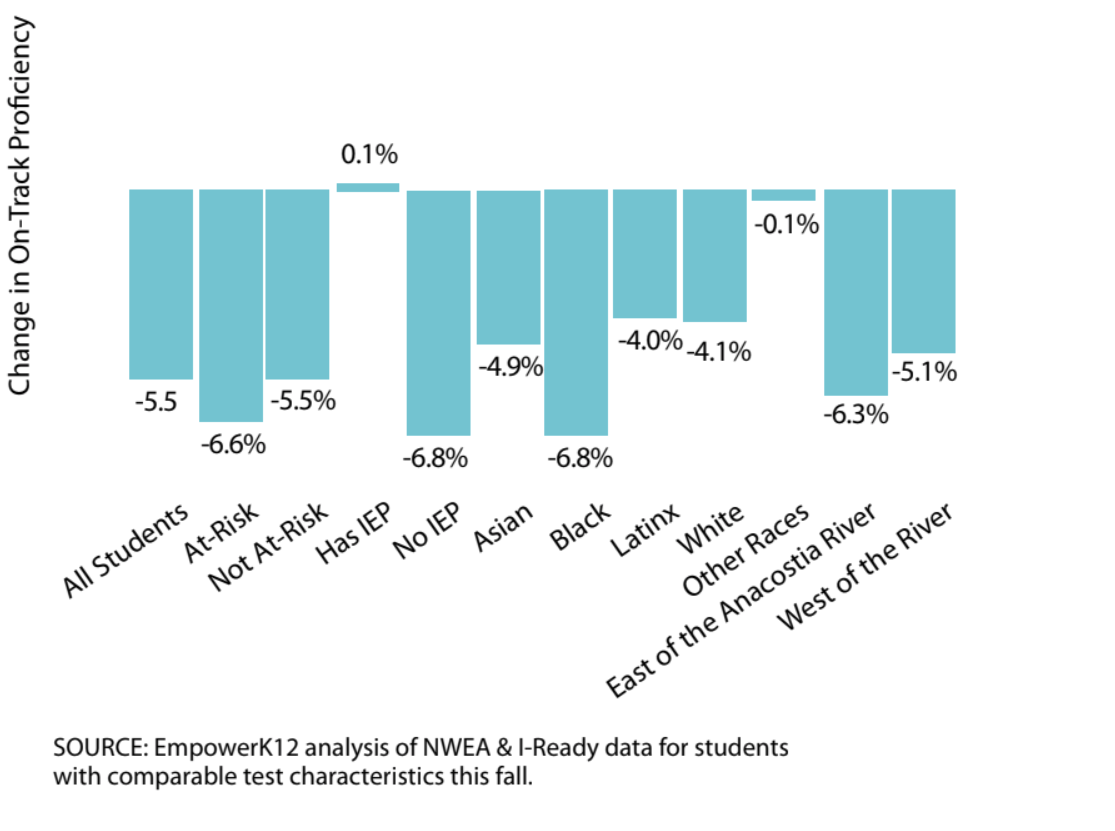

We also looked at whether D.C. students are on track to achieve proficiency on the national Partnership for Assessment of Readiness in College and Careers (PARCC) tests given in grades three through eight. Again, we found declines after several years of citywide growth. And again, the results exacerbated the city’s deep racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps.

Figure 2: Percentage of D.C. students on track for PARCC proficiency for reading in fall 2020, grades 3–8

Figure 3: Percentage of D.C. students on track for PARCC proficiency for math 2020, grades 3–8

We partnered with seven D.C. charter school networks and local school-based mental-health experts to gauge the pandemic’s impact on students’ emotional well-being through a DC Student Well-Being Survey. Most students reported anxiety related to the pandemic, with 77 percent concerned that their family would be exposed to Covid-19; nearly half reported that their family’s financial situation has become somewhat or significantly more stressful due to the pandemic. Nearly one in five students recently experienced the loss of a family member they live with.

The erosion of learning gains in the District during the pandemic suggests how fragile the benefits of school reform are, and thus the importance of staying the course on reform. And the fact that some students have fared better in reading during the pandemic while others have fallen further behind points to the importance of close connections between schools and families in closing achievement gaps and furthering the cause of educational equity.

Read the study here.

Editor’s note: This piece was originally published by FutureEd, an independent think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.