Set aside for a moment the debate about whether Elon Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) is an honest effort to cut waste, fraud, and abuse from the federal government. Let’s ask a different question: What would a serious effort to get more bang from our education buck look like?

First let’s state the obvious: We would want to start at the local level because, like money in banks, that’s where the spending is. You could get rid of the entire federal role in education and only save 10 percent of the cost of our schools, given that 90 cents of each dollar comes from the state and local levels.

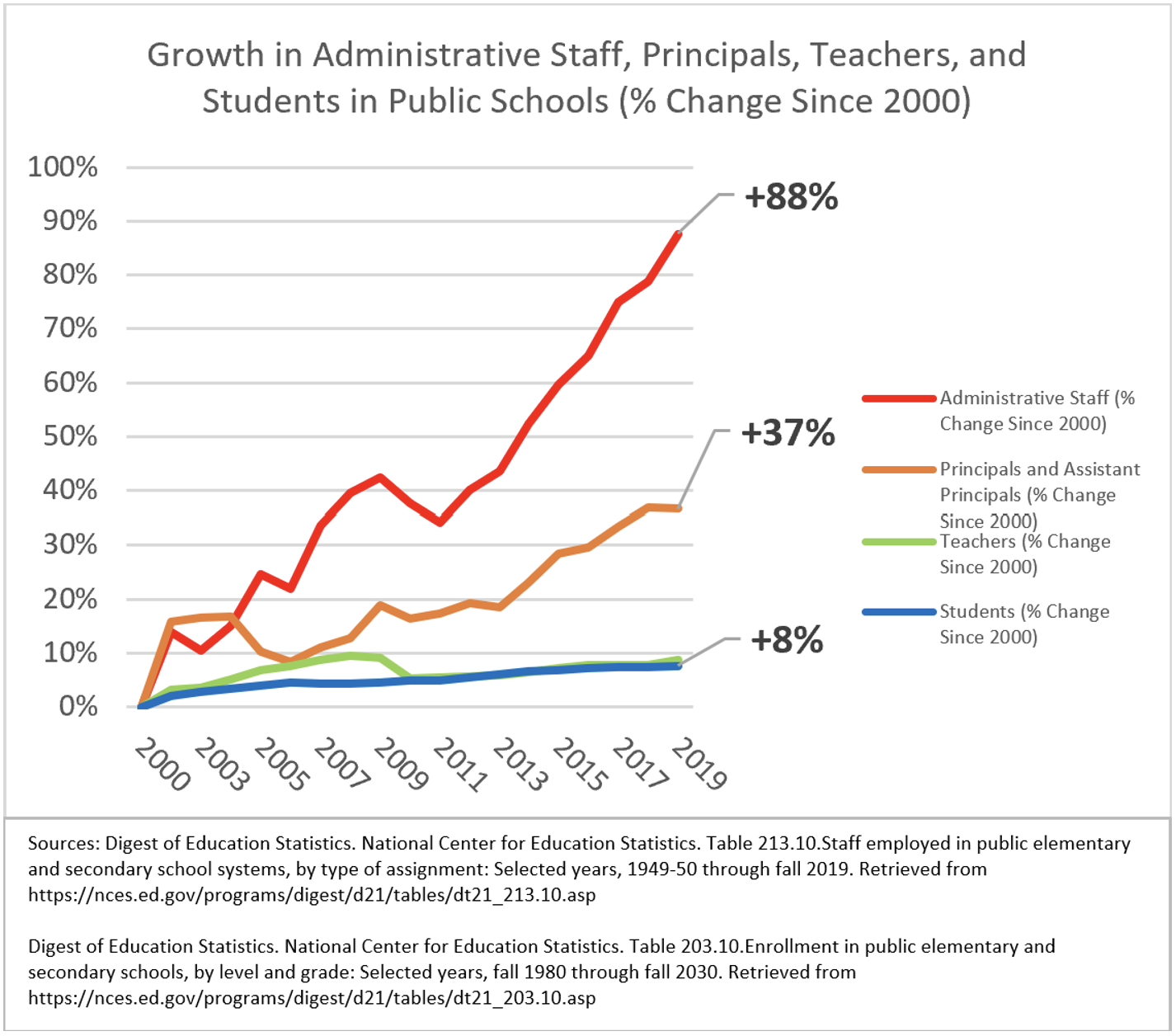

It’s also undeniable that we spend most of our education budget on staff—77.5 percent according to NCES. What’s perhaps not well known is that fewer than half of those employees are classroom teachers. Figuring out how to dramatically reduce the number of administrators and other non-teachers employed in our schools—as well as central offices—is a worthy goal.

Chart via Corey DeAngelis.

And yes, we could also wonder whether we might get by as well or better with fewer teachers (and larger classes). As Checker Finn remarked a few years ago, we could be paying every teacher six figure salaries if we had been willing to keep our class sizes moderate rather than pushing to make them smaller and smaller over the past half-century.

We’ve also known forever that paying teachers more for getting a master’s degree doesn’t add any value. It’s just a giveaway to the higher education industrial complex.

If we were willing to tackle just these three issues alone, we could achieve major savings without breaking too much of a sweat. Consider these back-of-the-envelope calculations:

1. Imagine that we reduced the number of non-teachers in our school system back down to the level we had in 2000, an era when our schools were making dramatic gains in student achievement. That would mean going from about 3.5 million non-teachers today to fewer than 3 million (the number back then). At a very conservative estimate of $41,000 per staffer (salaries plus benefits), that would save about $20 billion annually.

2. Now do the same when it comes to teachers and compute how much we could save by returning to 2000-era class sizes. That would mean increasing class sizes, on average, to about twenty-one for elementary schools and twenty-four for secondary, up from about nineteen and seventeen today.[1] Do the math and it means we need about 2.25 million teachers instead of the 2.79 million we have now, a reduction of roughly 539,000. At an average cost of about $87,000 per teacher (salaries plus benefits), that would save about $47 billion annually.

3. Now let’s see what we can save by eliminating those master’s degree supplements. They are worth, on average, about $5,000 per teacher, so that amounts to about $11.25 billion per year.

Boom. We just saved more than $78 billion, roughly 9 percent of the total cost of our education system. We could get there via attrition, and it would barely cause any pain.

Perhaps we could call it LOLCATS: Local Officials Lead Cuts via Attrition to Teachers and Staff. (Yes, I spent a lot of time on that!)

Now, as my friends on the right will tell you, I’m a big squish, so I don’t necessarily think we should take all those savings and just, say, give them back to taxpayers. I’d prefer to invest some of them in higher salaries for teachers, especially great teachers willing to serve in high-need schools, like Washington, D.C., and Houston are doing. To attract the best teachers to the toughest schools, the salary supplements need to be at least $10,000–$15,000 a year.

Let’s say we gave every single one of our 2.25 million remaining teachers a $10,000 raise, and another $15,000 raise on top of that for 1 million teachers in high-poverty schools. That comes to $37.5 billion—just about half of the amount we saved by modestly raising class sizes, reducing non-teaching staff, and eliminating the master’s degree pay bump.

What’s tough, of course, is getting from here to there. Given union politics, few districts will make these changes without state policy mandating them to do so. Perhaps the place to start is by forcing such changes on chronically low-performing districts—but I’m certainly open to other ideas.

—

Between staff cuts and grant and contract terminations, DOGE appears to have saved less than $2 billion in K–12 education spending so far. With my back-of-the-envelope exercise, I saved north of $78 billion (at least in theory). The main point is simple: In primary-secondary education at least, Washington’s not where the waste is.

[1] It’s possible these numbers are not apples-to-apples comparisons. It’s a little hard to believe that secondary class sizes decreased so dramatically in such a short period of time. I would call someone at NCES to better understand the definitions used back then and more recently—but those staff were all laid off.