The Covid-19 pandemic has further exposed the inequities that have long existed in K–12 education system. School closures due to the outbreak are particularly hurting low-income families and communities, and will likely exacerbate existing academic gaps, including the “gifted gap”—the difference in participation in gifted programs between low-income higher achievers and their more affluent peers. The longer schools remain closed and states struggle to devise re-opening plans, the greater the potential harm to bright students from low-income backgrounds.

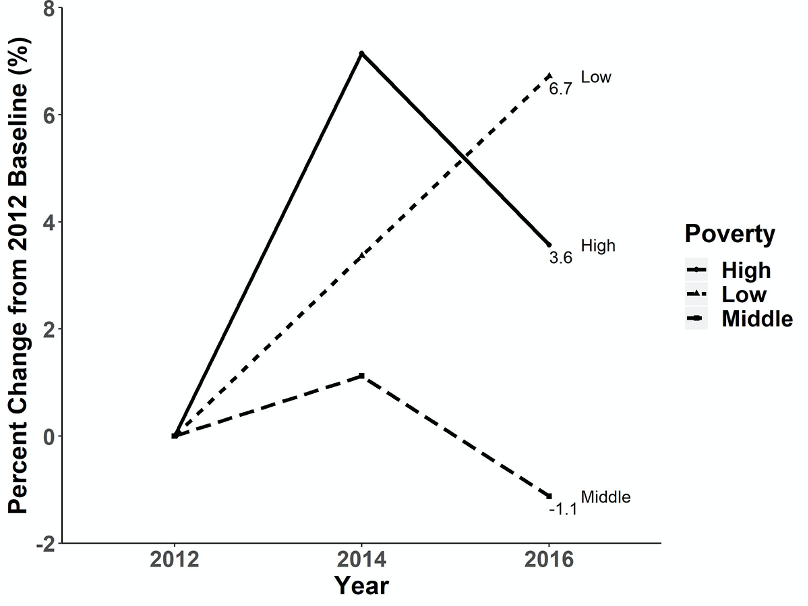

In 2018, when Adam Tyner and I published our report Is there a Gifted Gap?, the gap was already significant. We found that students in low-poverty schools participated in gifted programs at twice the rate of students in high-poverty schools. And in a recently published article, we found that the gaps have been growing. As Figure 1 shows, between 2012 and 2016, gifted participation in affluent schools increased by 6.7 percent, while only increasing by 3.6 percent in their less affluent counterparts. Middle-poverty schools saw an overall decline in gifted participation.

Figure 1. Percent change in gifted program participation between 2012 and 2016, by school poverty level

If high-poverty schools are not encouraging and cultivating young talent through high quality educational programs tailored to their achievement level as much as low-poverty schools, it may help explain why students from low-economic backgrounds continue to fall behind their wealthier peers

Sadly, we know that these gifted gaps are not primarily caused by differences in academic abilities. Research has shown that even among students with similar achievement and other background characteristics, higher-SES students are more likely to receive gifted services than lower-SES students, even within the same school. The problem is the system, not the students.

Our current study also shows that Black and Hispanic students continue to be statistically underrepresented in gifted programs. We did, nevertheless, find that the share of Hispanic students participating in gifted programs rose by 0.5 percent and 5.8 percent in all schools (low, middle, and high-poverty) and high-poverty schools, respectively. These increases can be attributed to an increase in the overall proportion of Hispanic students in our samples over the study period. For instance, in high-poverty schools, the proportion of Hispanic students increased from 36.3 percent in 2012 to 41.5 percent in 2016.

The question I normally get is, “Why should we care about high ability students?” As Checker Finn and Brandon Wright put it in their book, Failing Our Brightest Kids, “At the forefront of creation, invention, and discovery are—nearly always—the society’s cleverest, ablest, and best-educated men and women.”

Given our current pandemic and systematic crackdown of legal immigration by the current administration, it is perhaps more important now than ever that schools cultivate and nurture homegrown talents of all students, including high achievers. To prepare for the next global pandemic, we must also prepare the next brightest medical doctors, scientists, engineers, and policymakers.

To improve gifted participation and representation of bright students regardless of background or socioeconomic status, policymakers and administrators at the local levels must heed the research evidence that outlines strategies to combat the “gifted gap.” The good news is, we can achieve equity in these programs without compromising rigorous standards.