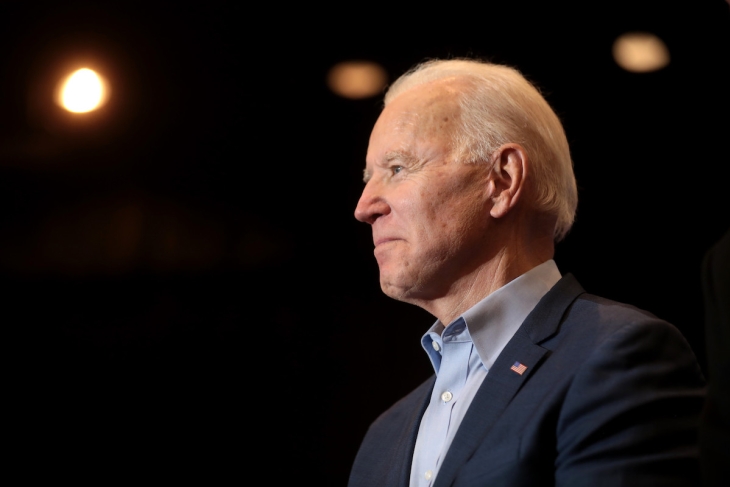

Besides pumping tons more recovery dollars into schools, getting more teachers vaccinated, and trying to get many more kids back into classrooms, what might the Biden-Cardona team do in K–12 education that would actually be worthwhile?

The big relief package that they’ve already outlined contains $170 billion for schools and colleges, which is roughly thrice the total annual federal outlay for elementary and secondary education. So significant funds are in play, but they’re nearly all earmarked for immediate recovery of school operations and student learning. Urgent, yes, but not the whole education story. More details will doubtless emerge from the new administration as to what they intend, and Congress will have a say, too. But—writing on a very welcome Inauguration Day—I have a few suggestions of my own. Most could be melded into the relief package. Or they can wait for the new FY ’22 budget request that the White House will shortly have to send to Capitol Hill.

I’ll set aside for now what we already know to be forthcoming efforts to undo parts of the Trump-DeVos era that the new team doesn’t like. In my view, some of that undoing will be harmful, especially at the Office for Civil Rights, and I’ll object. Perhaps partisan warfare is unavoidable, though my colleague Bruno Manno, who is always worth taking seriously, has offered a thoughtful “call for détente in the K–12 school wars” in The Hill. But putting politics and hot buttons aside for now, what else might Washington usefully contribute, not just to the revival, but also to the renewal of primary-secondary education in America over the next four years? Herewith an octet of recommendations:

1. Put the two most obvious conditions on those billions of additional school dollars. Insist that schools getting them actually reopen fast, especially for the hardest-hit kids. And insist that all schools, including charter and private, get their fair share of these funds. They, too, enroll millions of hard-hit students, and they, too, have been hit hard by the pandemic.

2. Beef up research and evaluation. The Institute of Education Sciences has a solid leader in Mark Schneider, whose term still has three years to run, but it has been starved for funds. All manner of important research has been neglected, especially pricey longitudinal studies and significant experiments. And the Covid-19 recovery period is a terrific opportunity to investigate a range of interventions. Schneider recently rekindled the idea of a “DARPA for education“ and has invited path-breaking research initiatives as a way to juice that idea. Assuming the Biden crew wants to “follow the science” in education as well as health, there’s no better place to focus than the one governmental entity dedicated to education science.

3. Revitalize the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Secretary DeVos’s letter to Congress explaining why the 2021 NAEP reading-and-math cycle needs to be delayed because of Covid-19 also contained a number of ideas for a NAEP refresh. Some of its testing practices are archaic. Tight budgets have forced long delays in assessing other subjects—and often make it impossible to do so in all three of NAEP’s grade levels (four, eight, and twelve). There’s an inexcusable dearth of state-level NAEP data for twelfth graders. And the NCLB-ESSA mandate to assess reading and math every two years for grades four and eight could easily be stretched to three or four. For better and worse, achievement just doesn’t change that fast!

4. Make a serious but cautious stab at strengthening civics education. Any number of recommendations are already available, some good, some pretty awful. More will soon be forthcoming from the Education for American Democracy project. This strengthening mission may prove fractious, and is surely a heavy lift, but something much needed by the country. At the federal end, it should continue to be shared with the Humanities Endowment and perhaps the Corporation for National and Community Service, not just the Education Department. Uncle Sam has to tread carefully here, of course, as he mustn’t mess with curriculum, and civics is inherently a touchy topic. (For example, “action” civics versus governmental nuts and bolts?) NAEP has a role to play here, too. So might some version of a “blue ribbon schools” award program? Summer institutes for teachers? A “presidential scholars” type program for kids? Support for a “civics bowl” or “civics bee”? And a lot of bully pulpit! Note, too, Bruno Manno’s suggestion in the aforementioned Hill op-ed that strengthening civics be linked to economic mobility and personal success.

5. Beef up career and technical education. This one needs to be shared with the Labor Department and other agencies, but it’s time for full-throated and sophisticated implementation of the re-enacted Perkins Act, now known as the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act. Combine this legislative update with an earnest push to legitimate high-quality career preparation as a worthy high school outcome and diploma pathway, while also connecting it to post-secondary opportunities that incorporate apprenticeships, as well as college and employment.

6. Refresh IDEA. Maybe this is politically unattainable, but only politics has kept special education from the overhaul that it has needed for at least twenty years. It’s too expensive. It’s too litigious. It’s overregulated. It encourages far too many kids to be “identified” after the fact instead of teaching them to read from the get-go. And once identified, far too many special ed students learn far too little. It’s been more about “rights” than about actual education, and that should change.

7. Hold the line on accountability. This is no time to give up on testing and school accountability—and one of Secretary Cardona’s toughest early decisions will be whether to offer another round of ESSA testing waivers. He shouldn’t—and if he does, states shouldn’t take them. (Or if they must wait until autumn to get most of their pupils back into classrooms, states should schedule 2021 testing for first thing in the fall.) That doesn’t mean this year’s scores need to be used for school accountability, but information on where kids are—and aren’t—academically is vital if recovery is to occur. Thereafter, however, it’s essential to recommit to results-based school accountability. That doesn’t mean current state ESSA plans are perfect. It may be time to encourage a rewrite. Which brings me to the final instrument in this octet.

8. How about another summit? It’s been an astonishing thirty-two years since Bush 41 assembled the nation’s governors to focus state and federal education leaders on the urgency of reform, and frankly, a lot of governors seem to have tuned out even as much has changed. Without renewed high-level attention from state and national leaders, we’re apt to slip back into our tired old ways instead of formulating bold plans for recovery, determining what changes from pandemic-era schooling to keep, and more generally, charting the next generation of K–12 reform at every level.

—

To repeat, some of these suggestions could be worked into stimulus funding, others into the Fiscal 2022 budget. The summit and one or two others could be done via executive action. Others need legislation. Détente among all the battling education factions may be a bridge too far, but bipartisanship on a handful of worthy federal initiatives may not be too much to hope. It’s got to start somewhere, however—and the new administration’s first hundred days feels like the right place to begin.