About three-quarters of students in the U.S. take at least one credit in high school linked to career and technical education (CTE). When high school students take multiple CTE credits, they are often encouraged to focus in a specialized career pathway, like business, health sciences, or hospitality and tourism.

The idea behind this type of CTE specialization in high school is twofold. First, it gives students a chance to explore a career they might be interested in pursuing. Second, it helps prepare them for a postsecondary degree, credential, apprenticeship, or job in that field.

On both fronts, CTE specialization should, in theory, help students hit the ground running after high school by streamlining and aligning their interests, skills, and knowledge. In fact, both our research and a new report from the Fordham Institute indicate that most students who focus on a CTE field in high school go on to work and study in other fields.

Understanding whether students continue with specializations they begin in high school matters because of growing interest in CTE and the wide variation in college completion and labor market returns across fields, but it also matters because of recent drops in postsecondary enrollment—especially at community colleges and for students from underserved communities.

To find out more, our study followed four statewide cohorts of high school graduates in Kentucky between 2013 and 2016. Unlike prior survey-based research on the topic, we used detailed data from administrative records, including data on student achievement, the number and type of CTE courses students took in high school, postsecondary enrollment, and college majors. These data gave us a detailed picture of the relationship between CTE specialization and postsecondary outcomes.

We used the data to look at whether students who took four or more credits in high school (what we call “CTE concentrators”) more or less likely than non-CTE concentrators to stick with that field after high school. Around 70 percent of CTE concentrators specialized in a particular pathway. We were able to look at the results across four broad CTE pathways: Health, Business, Applied STEM (e.g., computers, engineering technology), and Occupational Fields (e.g., social work, firefighting, and childcare).

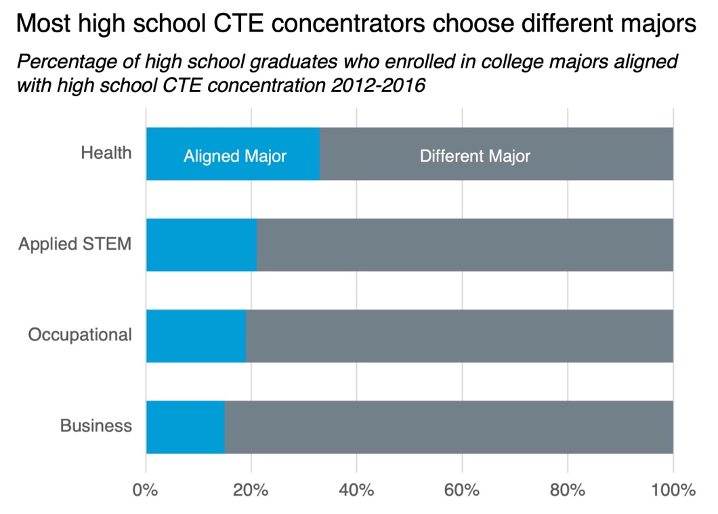

Overall, we found that most students with CTE specializations, regardless of pathway, ended up studying something different when they got to college.

As the above chart shows, the majority of CTE concentrators in all four areas ended up majoring in a different subject in college (the grey portion of the bars). But the chart also shows the results vary by concentration. Larger shares of students with CTE specializations in Heath (33 percent) and Applied STEM (21 percent), for example, majored in those same areas in college compared to students who specialized in Occupational Fields (19 percent same major in college) or Business (15 percent same major in college).

Even though most CTE concentrators didn’t end up majoring in their concentration in college, they are still more likely to major in their area than students who don’t concentrate in CTE in high school. The odds of majoring in Applied STEM in college, for example, more than double if a student specializes in Applied STEM in high school (from 6 percent to 17 percent).

Our findings about college credentials (including associate’s and bachelor’s degrees) were also mixed. Similar to decisions about choosing a major, most college students who specialized in a CTE field in high school attained credentials in a different field, if they attained any credentials at all. For example, among the credentials earned by college students who specialized in Health in high school, 55 percent were in a field other than Health. For college students who specialized in other CTE fields in high school, more than 70 percent of the credentials they earned were in a different field.

However, CTE specialization in high school increased the odds of completing an AA degree or higher in the same field of concentration relative to non-CTE concentrators. The increased odds range from 34 percent in Occupational Fields to 2.8 times in Applied STEM.

Where does this leave us? Above all, the results of our study and Fordham’s recent report—both the breakdown between CTE concentrations and college majors and the differences across CTE areas—underscore how important the decisions students make about CTE are. On the margin, the effects of CTE specialization clearly matter. But the broader breakdown between specialization and college majors raises questions about where and why students get off track: a missed opportunity, lack of information and support, or a shift in student preferences? Maybe specialization helps students realized what they are not interested in pursuing?

It’s also clear that schools need a better understanding of how students make decisions about CTE and what would improve them. For example, research shows that students, particularly historically underrepresented students, are not always responsive to information on labor market earnings when it comes to choosing what to study in college. On the other hand, information on students’ own abilities and preferences plays a much larger role in determining such choices. To help students gather such information, a sensible policy option is to provide free, universal assessment of college and career-readiness early and more experiential learning opportunities to complement classroom-based learning.