The ESEA reauthorization conferees delivered some good news for America’s high-achieving students last week. Absent further amending, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) will include a necessary and long-overdue section provision that allows states to use computer-adaptive tests to assess students on content above their current grade level. That’s truly excellent news for kids who are “above grade level”—and for their parents, teachers, and schools.

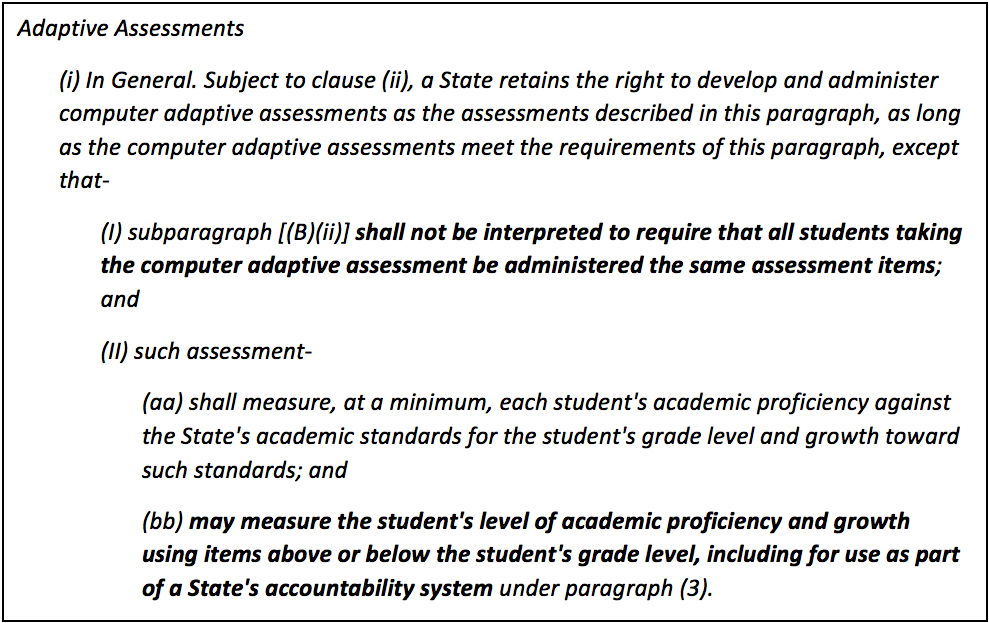

Here’s the language, with emphasis added:

The quality of state assessments matters enormously to children of all ability levels, but today’s tests do a grave disservice to high-achievers. Most current assessments do a lousy job of measuring academic growth by pupils who are well above grade level because they don’t contain enough “hard” questions to allow reliable measurement of achievement growth at the high end.

Doing that with paper-and-pencil tests would mean really long testing periods. But a major culprit is an NCLB provision requiring all students to take the “same tests” and (at least as interpreted during both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama presidencies) barring material from those tests that’s significantly above or below the students’ formal grade levels. Though the intentions behind this decision were honorable—to keep states from setting lower expectations for and administering easier tests to low achievers—it has curbed the use of computer-adaptive testing and other strategies that can accurately and validly detect student growth at the high end. Without evidence of this growth, there’s no way of giving credit to the schools that produce it.

Computer-adaptive assessments (such as those developed by the Smarter Balanced consortium) can be structured and administered in ways that measure growth at every level, without overburdening any student with a ridiculously long test. But Department of Education officials haven’t let Smarter Balanced use the full potential of its platform to test students using above- (or below-) grade-level items. This means that we don’t have an accurate read on just have far above (or below) grade level some students may be.

If the reauthorization stays on course, that hurdle goes away. But then it’s up to the states, which will be in the testing-and-accountability driver’s seat, to figure out how to do this and to insist on tests that make it possible. If combined with a real growth model—holding schools accountable for making sure that all students make progress over the course of the school year—states can finally create incentives for schools to pay attention to their high achievers too.

Picture a fourth grader who is doing math at levels typical of the state’s sixth-grade academic standards. She’ll “top out” on a fourth-grade math test. It won’t be able to report how much she learned that year, nor give her parents and teachers feedback on how she’s really doing, nor give her school credit for moving her ahead. An adaptive test can do that. And that’s what we should be doing. American education has focused in recent decades on ensuring that all children attain a minimum level of academic achievement. That is an absolutely worthy goal, and we’ve made some progress toward it. But kids already above the “proficient” bar deserve attention as well. This new statutory language makes that possible.