Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series of blog posts taking a closer look at the findings and implications of Evaluating the Content and Quality of Next Generation Assessments, Fordham’s new first-of-its-kind report. The first three posts can be read here, here, and here.

It’s historically been one of the most common complaints about state tests: They are of low quality and rely almost entirely on multiple choice items.

It’s true that item quality has sometimes been a proxy, like it or not, for test quality. Yet there is nothing magical about item quality if the test item itself is poorly designed. Multiple choice items can be entirely appropriate to assess certain constructs and reflect the requisite rigor. Or they can be junk. The same can be said of constructed response items, where students are required to provide an answer rather than choose it from a list of possibilities. Designed well, constructed response items can suitably evaluate what students know and are able to do. Designed poorly, they are a waste of time.

Many assessment experts will tell you that one of the best ways to assess the skills, knowledge, and competencies that we expect students to demonstrate is through a variety of item types. In our recent study Evaluating the Content and Quality of Next Generation Tests, we used as our benchmark the Council of Chief State School Officers’ 2014 Criteria for Procuring and Evaluating High-Quality Assessments.

One aspect of item quality that the CCSSO criteria emphasize is a diversity of item types. To fully meet this standard, ELA tests must utilize at least two item formats, including one that requires students to generate (rather than select) a response.

How did the four tests reviewed (ACT Aspire, MCAS, PARCC, and Smarter Balanced) fare on this requirement?

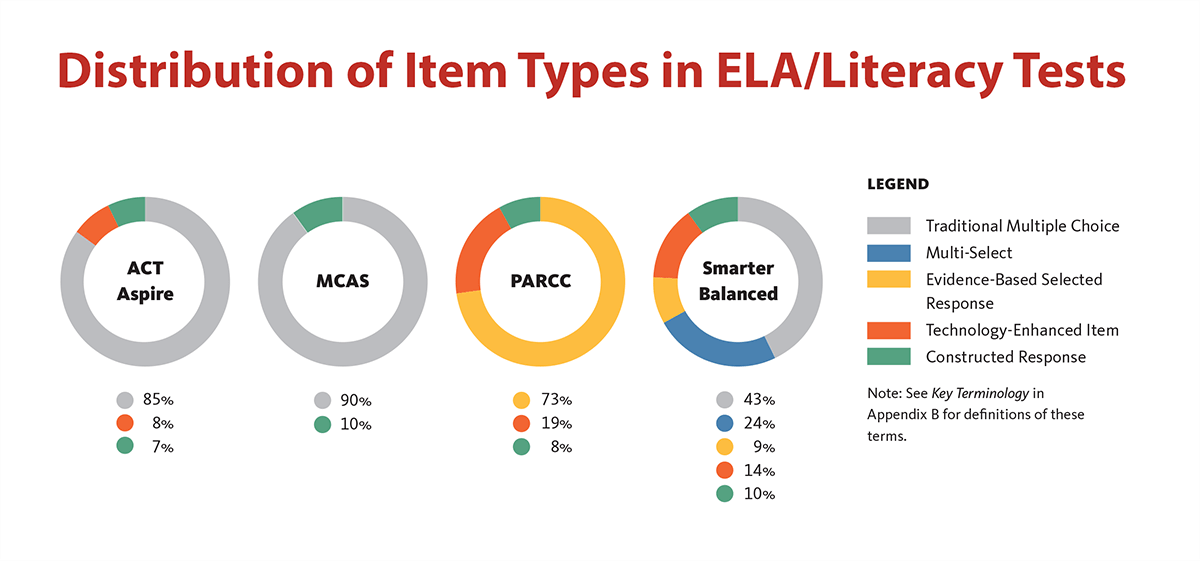

Our reviewers found that all four programs use multiple item types for their ELA tests, including at least one student-constructed response type, so they all met this portion of the criterion. But the actual variety of item types differed much more significantly, as shown below.

PARCC and Smarter Balanced typically had the widest range of item types, including constructed response, evidence-based selected response, and technology-enhanced. (The latter two item types require students to provide evidence to support their answers and to perform some action that cannot be executed on a traditional paper-and-pencil test, respectively.)

In particular, our ELA reviewers commended the innovative and appropriate use of technologies within Smarter Balanced and PARCC items, such as audio files in listening items and text editing. While also computer-based, the ACT Aspire assessments had a much more limited set of item types that heavily relied on traditional multiple choice items. The 2014 MCAS is a paper-and-pencil test that has a near-complete focus on traditional multiple choice items, cited by several reviewers as a serious limitation.

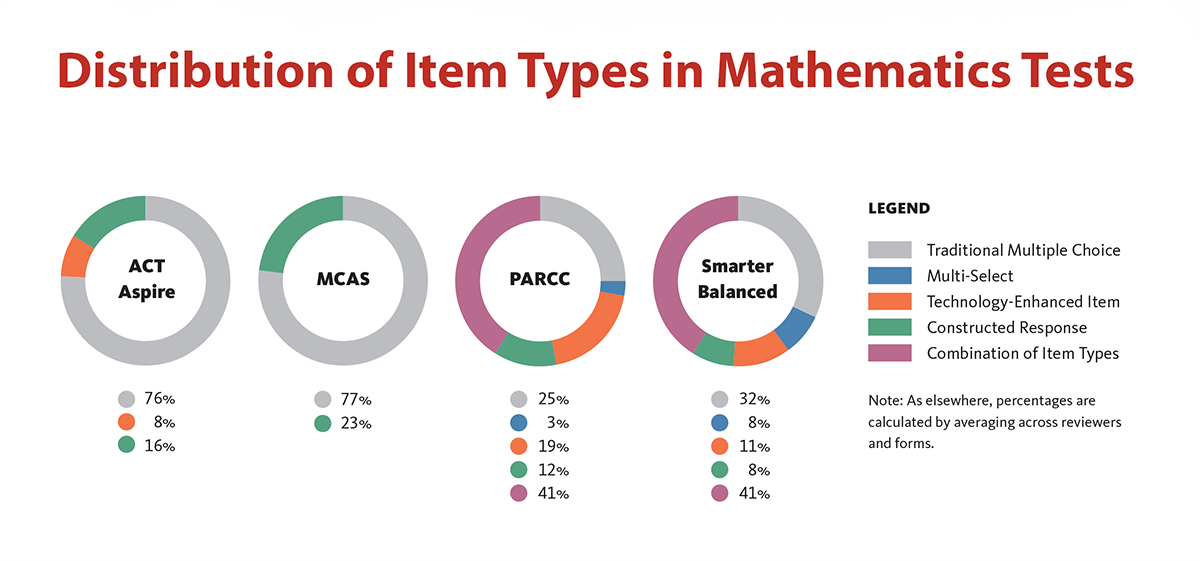

All four programs also used multiple item types for math, including at least one student-constructed response type, so they all met this portion of the criterion. But as with ELA, the actual variety of item types differed significantly, as shown below.

As with ELA, PARCC and Smarter Balanced typically had the widest range of item types, including multiple choice, constructed response, multi-select, and technology-enhanced. Both of these assessments featured traditional multiple choice items as less than 50 percent of their content. In contrast, both ACT Aspire and MCAS presented 75 percent or more items as traditional multiple choice items.

Most of us can agree that multiple-choice-only tests cannot fully measure complex student skills. For instance, the ability to read several texts about a topic and craft a well-written argument supported by evidence is an important skill for all high school graduates—one that is nearly impossible to measure through multiple choice items. But as we discuss in our report, items that measure such complex competencies also take more time. That’s a tradeoff that we consider worth making, but a tradeoff nonetheless.

A wider variety of item types (birthed out of a rigorous research and development process) will help us assess the more robust skills, knowledge, and competencies that we expect our young people to master before leaving high school. But some of those things we’re not yet measuring well. For instance, the mathematical practices call for high school students to adeptly use common technologies such as spreadsheets and statistical software. Yet we need advances in technology-enhanced items (not to mention computer bandwidth at schools) to incorporate such technological tools. Similarly, the ELA standards call for students to express orally well-supported ideas, but no current state test includes the assessment of speaking skills. Great advances have been made in the testing industry over the past five years, especially as the majority of states have transitioned to computer-based delivery. Still, we still have miles left to travel.