This is the fifth in a series in which I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. Previous pieces covered the science of reading, funding for low-income pupils, interdistrict open enrollment, and guarantees. This essay looks at funding for public charter schools.

For more than two decades, Ohio’s charter schools—nonprofit public schools that operate independently—have served families and students seeking non-district options. In 2023–24, approximately 85,000 students, mostly from urban communities, attended one of the state’s 318 brick-and-mortar charter schools. Studies have shown that charter students learn more in math and reading than similar students who attend nearby district schools.

Despite their value to parents and students, Ohio has—until recently—significantly underfunded its charter schools. An analysis of FYs 2015–17 data found that charters received on average just 68 percent of what nearby traditional districts received in total funding, a shortfall that hamstrung charters when it came to paying competitive teacher salaries and providing student services. It was also a fundamentally unfair system to charter students, who are disproportionately poor and from communities of color, and whose education was funded at lower amounts simply by virtue of their choice in public school.

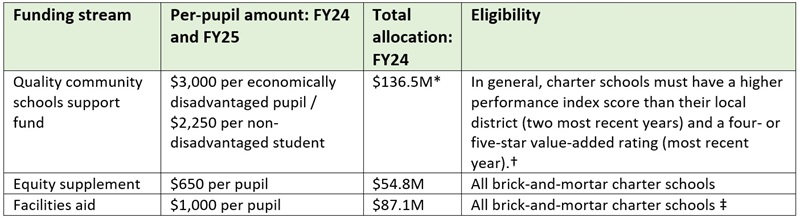

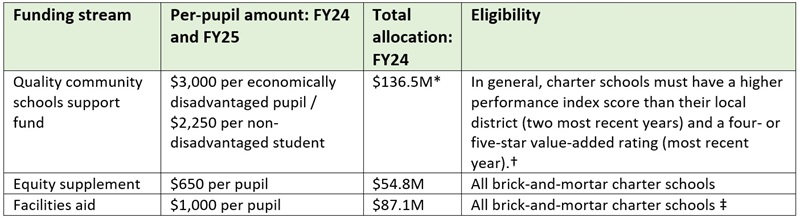

To their credit, state policymakers have taken steps to move charter funding closer to parity with districts. The effort began in 2019 when Governor DeWine proposed a new funding supplement for high-performing charters. His initiative sailed through the legislature and was launched in FY 2020. In last year’s historic budget bill, lawmakers doubled down on this program by significantly increasing the per-pupil allotments. They also created a new “equity supplement” that supports all brick-and-mortar charters, not just those qualifying for high-quality funding. Lastly, in the realm of school facilities—an area in which charters have also been shortchanged—lawmakers doubled the state’s facilities allowance in the last budget. Table 1 below summarizes these funding initiatives.

Table 1: State programs that help to narrow charter-funding gaps

* This is the total budgeted amount for the program per House Bill 33—not the actual program spending for FY24, which came in less than budgeted based on the number of qualifying schools and their enrollments. Independent STEM schools (seven are in operation) are eligible for these funds, as well. † Schools must also serve a majority economically disadvantaged students and have a sponsor with at least an “effective” state rating. New startup charter schools may qualify for funds under alternative criteria. ‡ Independent STEM schools also receive these funds. Online charters receive a $25 per pupil facilities allotment.

* This is the total budgeted amount for the program per House Bill 33—not the actual program spending for FY24, which came in less than budgeted based on the number of qualifying schools and their enrollments. Independent STEM schools (seven are in operation) are eligible for these funds, as well. † Schools must also serve a majority economically disadvantaged students and have a sponsor with at least an “effective” state rating. New startup charter schools may qualify for funds under alternative criteria. ‡ Independent STEM schools also receive these funds. Online charters receive a $25 per pupil facilities allotment.

These additional dollars empower charters to compete for educator talent and provide extra student supports—factors that are critical to supporting higher student achievement. They make it possible for charters to expand and replicate, thereby providing even more students and families with quality options. And the push towards equitable funding has also made Ohio a more attractive locale for high-performing national charter networks. Texas-based IDEA Public Schools and classical charters affiliated with Hillsdale College (MI), for example, recently launched their first schools in Ohio.

Thanks to Governor DeWine and recent General Assemblies, charter funding has come a long way in a short time. But there is still work to do to erase funding gaps and ensure that recent gains aren’t temporary. Excluding the facilities aid,I estimate that high-quality charter schools are now receiving roughly 90 percent of what local districts receive, while other charters are funded at approximately 75 percent. That’s better but not good enough. In the next biennial budget, state lawmakers should pursue the following items.

1. Build on the equity supplement to move all brick-and-mortar charters towards fairer funding.

Ohio’s push to improve charter funding has focused heavily on schools achieving strong marks on their state report card. This year, fifty out of 318 brick-and-mortar charters met the quality funding program’s performance criteria. Policymakers should continue to support quality charters and maintain a high bar for receiving those dollars. But they also need to continue to move towards equitable funding for all charter students, including those attending non-qualifying schools. Remember that many of their students are high-needs: low-income, students with disabilities, or—in the case of dropout-recovery charters—adolescents who have fallen significantly behind in their education. Furthermore, a boost in funding is one of the surest ways to help these schools go from mediocre to good or from good to great.

As noted earlier, lawmakers created a $650 per pupil equity supplement that supports all brick-and-mortar charters in the last biennial budget. This is an excellent foundation upon which legislators can build. During last year’s budget discussions, we at Fordham and others recommended a $1,000 per pupil equity supplement. Reaching that amount in the next budget would further narrow the funding gap for brick-and-mortar charters statewide.

2. Ensure the facilities allowance keeps pace with inflation, while pursuing new charter facility initiatives.

Historically, charters have been unable to access the capital resources that districts can tap into. For example, charters do not receive proceeds from local bond levies and are ineligible for the state’s main school construction program. To help cover charters’ facility costs, lawmakers introduced a charter-specific facilities allowance during the Kasich administration. Thanks to steadily increasing per-pupil allotments, a recent analysis by ExcelinEd finds that Ohio now covers roughly half of charters’ facility needs. In the next budget, lawmakers should increase the $1,000 per-pupil facilities aid to adjust for inflation. Beyond a boost in the per-pupil facilities aid, policymakers should also pursue additional initiatives that would allow charters to address their building needs, such as credit-enhancement and revolving-loan programs and revisions to state law that would make it easier for charters to access unused district facilities.

3. Cement the high-quality funding, equity supplement, and facilities aid into charter schools’ permanent funding formula.

Currently, all three programs are funded through appropriations language in the state budget bill, which means they are not technically part of Ohio statute. This particular method of funding sends a signal that these programs are temporary and increases the risk that future General Assemblies will eye them for cuts. In the next budget bill, lawmakers should make these programs part of charter schools’ funding formula, which is established in statute. While it wouldn’t make them impervious to legislative change, formally including them in the formula would make it clear that the programs are crucial components in Ohio’s charter funding model. Moving these programs into the formula would also protect the per-pupil amounts set forth in bill language from reductions necessitated by funding these initiatives via line-item appropriation—something that occurred to the high-quality funding in FYs 2020–23 and the facilities allowance in FY24.

* * *

Students attending Ohio’s public charter schools deserve fair funding, just like their peers attending traditional district schools. Fortunately, Ohio’s policy leaders have recognized this imperative and have taken important steps forward that narrow funding gaps. More work remains to ensure equitable for all charter students, and the next budget cycle is another opportunity for lawmakers to move further in this direction.

Facilities aid is excluded because I do not include district capital outlay when calculating the district-charter funding gap. These projections are for the Ohio Big Eight charters (where the vast majority of brick-and-mortar charters are located) and based on FY23 fiscal data but include the FY24 quality and equity funding amounts (FY24 fiscal data are not yet available).