Rarely do you see media coverage in Ohio about a public charter school embarking on an ambitious expansion. It’s not that the press is hostile to charters; it’s that such expansions don’t often occur in Ohio. That’s because Buckeye charters typically lack access to the resources that allow them to undertake large-scale capital projects. It’s also why recent news reports about Cornerstone Academy are worthy of note. The 1,000-student Westerville charter school managed to secure $30 million in bond financing via the Columbus-Franklin County Finance Authority for a significant facilities project.

This is terrific news for Cornerstone and its students. Yet those same articles illustrate a shortcoming in Ohio’s charter facility policies: lack of access to affordable financing for capital projects. Cornerstone will be paying 7 percent interest on the bond. While that seems normal in today’s high-rate environment, it’s still a lot to pay for debt service.

And it’s a lot more than traditional districts typically pay for capital projects. Dublin City Schools, for instance, recently secured $95 million in bond financing at 3.99 percent interest. Similarly, Bowling Green City Schools just obtained $73 million in financing at 4.08 percent.

It is true that charters, unlike districts, can close or be closed and they don’t have the power to tax, factors that may help to explain Cornerstone’s higher interest rate. But—just like districts—charters are public schools, held fully accountable for being fiscally responsible, as well as for their academic results. Charters also provide tens of thousands of Ohio families with additional public school options, and on average, they outperform their local school district.

To grow at scale, charter schools need access to more affordable financing. The high cost of debt servicing discourages many charters from undertaking capital projects in the first place, which often means they operate in less-than-optimal facilities. And when they do embark on substantial facilities improvements, the high interest rates they must pay tie up more of their budget with debt service and leave fewer dollars for classroom instruction. Given these challenges, it’s no surprise that only a handful of Ohio charters have ever accessed bond financing for capital projects.

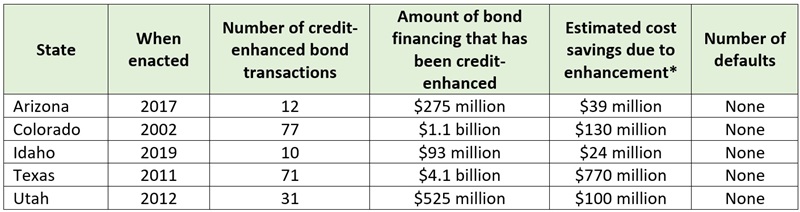

Recognizing this problem and the disadvantage it poses to charter schools and their pupils, five states—Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Texas, and Utah—have created “credit enhancement” programs. Ohio lawmakers should do that, too. But what exactly are these programs, how are they structured, and what savings do they actually deliver?

A recent report from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) provides a useful guide. LISC describes such programs this way:

State bond credit enhancement programs represent one of the most effective and least costly options available to lower the cost of financing for charter school facilities. These programs significantly reduce taxpayer dollars spent on facility debt service by effectively substituting the state’s generally far superior credit rating for that of the charter school, resulting in a lower interest rate and reduced debt service payments.

LISC notes two basic approaches to providing enhanced credit:

- Formal guarantee: Arizona and Texas guarantee—legally obligate—the state to cover bond payments in event of a default. In these states, charters were incorporated into a larger bond-guarantee program that is available to school districts.[1]

- Moral obligation: Colorado, Idaho, and Utah pledge—via a non-binding “moral obligation”—that the state will provide funds to cover payments if a charter school defaults.

Both routes effectively enhance the credit of charter schools, usually just a notch below a state’s own credit rating but higher than the rating a charter would receive on its own.[2] States, of course, do not actually pay the regular bond principal and interest—that remains the responsibility of the school. They only intervene if a school does not make a payment. This added layer of security reduces the risk to creditors and lowers charter schools’ interest rates.

To insulate the state from risk, states set aside an up-front amount to cover the possibility of default. In Colorado, for example, the legislature initially appropriated $1 million as a dedicated reserve fund, and over the years, it’s added another $6.5 million to it. Another $8.1 million has been contributed from participating charter schools, which pay a nominal fee to receive the enhanced credit, along with another $1 million from interest earnings. With no defaults—and thus no draws on the reserve—Colorado’s reserve fund stood at $16 million as of 2023.

In addition to maintaining a reserve, states also set minimum criteria that charters must achieve to receive enhanced credit. In Colorado and Utah, for instance, a charter must receive, prior to participating, a non-credit-enhanced investment grade rating to participate. This, too, minimizes the risk to the state—and as the table below indicates, no defaults have actually occurred in states with bond enhancement programs for charters.

According to the LISC analysis, credit-enhancement programs in other states have delivered huge savings to participating charter schools. In Colorado, for example, $1.1 billion in charter facilities financing has been credit-enhanced, saving schools $130 million in debt service expense. Texas’s credit enhancement program has produced some $770 million in savings for its charter schools. These savings have been accomplished, again, without any defaults on a credit-enhanced bond.

Table 1: Credit-enhanced bond financing for charter schools, and estimated cost-savings

* * *

The bottom line is that, by enacting supportive facility policies, other states have enabled quality charter schools to expand and thus to serve more families and students. In fact, some of the nation’s finest and fastest growing charter networks—e.g., Basis, Great Hearts, and IDEA—call these states home. Regrettably, Ohio still lags behind. Creating a strong credit enhancement program would go a long way toward enabling Ohio’s best charters to educate more students.

[1] Ohio does not appear to have a formal guarantee program for school district bonds, so it may be more challenging to go in this direction.

[2] The State of Ohio currently has the top credit rating possible.