On this week’s Education Gadfly Show podcast, Adam Tyner, Fordham’s national research director, joins Mike and David to discuss his latest study on advanced education policies across the country. Then, on the Research Minute, Amber examines new research on how the decentralization of teacher accountability under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act affected student achievement.

Recommended content:

Feedback Welcome: Have ideas for improving our podcast? Send them to Daniel Buck at dbuck@fordhaminstitute.org.

Michael Petrilli:

Welcome to the Education Gadfly Show. I'm your host, Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B Fordham Institute. Today Fordham's Adam Tyner joins us to discuss his latest study on advanced education policies across the country. Then on the research minute, Amber reports on a new study investigating the effects of the rollback of teacher accountability under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act. All this on the Education Gadfly Show.

Hello. This is your host, Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at fordhaminstitute.org. And now please welcome our special guest for this week, Adam Tyner. Adam, welcome back to the show.

Adam Tyner:

Thanks for having me back.

Michael Petrilli:

Yeah, Adam is the national research director here at the Fordham Institute. Also joining us as always, also from Fordham, my co-host, David Griffith. That's right. All Fordham all the time today. And that must mean we are talking about a new Fordham study. Let's do that on ed reform update.

Okay. Adam, new study by you. It's called the Broken Pipeline Advanced Education Policies at the local level. This was a project that in some ways goes along with our national working group on advanced education. That final report came out last year. Great group of people left, right, and center, scholars, practitioners, policy makers sending, hey, when it comes to advanced education, including things like gifted and talented programs or advanced advanced courses in high school, when people are worried about equity, the goal should not be to end it, but to mend it, to extend it, to get lots more kids into advanced education, kids who could benefit from it. This study is based on a survey of school districts and charter networks trying to find out what's going on out there at the local level. How many of these practices are in place? First of all, Adam, just real quickly tell us about the survey. Who was it that we got this information from?

Adam Tyner:

So this was a survey of district administrators. So it was people who were working in districts and we primarily targeted people whose portfolio was around advanced or gifted education. So many districts around the country have an administrator that serves to coordinate different types of advanced programming in that district, although some don't. And so in some cases we targeted just the superintendent or an assistant superintendent who had an academic portfolio. But these are district administrators telling us about the policies that they have in their districts.

Michael Petrilli:

Okay. And how many? A few hundred, right? How many respondents here?

Adam Tyner:

Yeah, I think we're somewhere around 500.

Michael Petrilli:

Yeah. Alright. So this is a big, big group people you were able to, then you've got data on these school districts, so you're able to wait it. So we are able to see, get basically a representative, look at what's happening across the country. So as I read it, Adam, the good news is that there is indeed a lot of universal screening going on out there for gifted education programs. This is one of the big recommendations of the report. Also comes out of a great study by Nobel Prize winning economist David Card and a working group member Laura Juliano, which says that you want to do universal screening, meaning don't just rely on recommendations from teachers or from nominations, from parents about who should be in gifted education. Use something like a standardized test score to look at everybody. And that's actually quite prevalent out there, right?

Adam Tyner:

Well, after I worked up all of these charts and graphs and came up with some findings and everything we were all talking about, and we kept going back and forth about whether the glass was half full or half empty, was it good? Was it bad? And I feel like universal screening for me is one of those where the glass is maybe like three quarters full because we find that there's a lot more universal screening than I think people thought. And in 77% of the districts in the country, we see that they're doing some kind of universal screening based on a standardized test. Now when you dig into that and start finding out, well, how does that work in the district? One thing that I'm still a little bit disappointed by is that in many districts that just is happening in one or two grades. So there's not a ton of on-ramps, even though screening is universal. But universal screening is happening more commonly than I think a lot of people thought.

Michael Petrilli:

So, right? They may be using the third grade state test or something like that, or maybe they're using an i-Ready scores or MAP scores, but they're only doing it for a few grades. Now, the other bad news, and this is a big one when it comes to identifying kids, is they are also generally not using local norms. Now, this is a term that people in the advanced dead world talk about a lot. Again, it came out of some studies by David Card and Lord Giuliano. And the idea of a local norm is saying, Hey, you should select kids who are scoring at the highest levels in their school, even if that doesn't necessarily mean that they're all that high achieving within their district or their state, right? And yet there's places where they still say, to be identified for advanced education, you got to score at the 97 percentile nationally. And what we're saying is that it would be better to just maybe take the top 10% of kids in every school, and we mean every school, so that every school, including high poverty schools, would have gifted education programs and they'd serve kids who are just higher achieving than their peers and therefore need some extra challenge. But that is not as prevalent around the country.

Adam Tyner:

That's right. We see that 20% of districts are using some kind of district norm, about 20%. It's 21% I think are using a school norm. Those are the kind of local norms that we're looking for. And like you said, Mike, that's especially important in places that are generally on average lower achieving, right? Because if on average people are lower achieving, then that means that we may not be capturing, there may be nobody in that top 5% nationally or whatever if you're setting a national norm. But if you set the bar at the top 10% in your school, then you're still going to capture those students who are really ready to excel beyond their peers, but are not meeting that super high kind of arbitrary national standard.

Michael Petrilli:

Now that said, one thing that was interesting is that you did not really find any major differences based on the demographics of the districts. Fair enough that when you look at the overall, at least across a lot of different policies, and I should be clear a lot more in here than just identification, we'll get a little bit to that in a minute. But on all these policies and practices, for the most part, the districts look more similar than different.

Adam Tyner:

To me, that's one of the glass is completely full findings of this report is that when we look, we made this index where we tried to look at the policies that we thought were the most important for districts to have, and then we tried to score them. So if you had did universal screening, for example, you got more points and we turned that all into an index so that we could really compare at a macro level, how is this district doing versus that district? And when we look at the scores of districts by poverty, by race, by the size of the district, we really don't find much difference when we look at that. We don't just look at some binary like high or low poverty. We look at it by quartiles. We're really getting some nuance and we just don't see the scores being much different.

They're very similar. Now, I think larger districts did tend to have a very slightly higher score on our index, meaning they had slightly more comprehensive policies than the smallest districts that we included. But when you look at race and socioeconomic status, it is not a good predictor of the comprehensiveness of the policies. And actually this is a finding that is similar to something that we found in one of the first reports I did for Fordham back when in I think 2018, I did a report as co-authored with now Dr. Chris Lum, he just got his PhD at Ohio State a couple of weeks ago. I think he defended his dissertation. But he and I worked together to look at federal data and look at the prevalence of just having a gifted program in higher versus lower poverty schools. And we found a similar pattern, meaning that there was no pattern. It wasn't that higher poverty schools were more or less likely to have gifted programs. Of course, fewer students are enrolled in gifted programs in higher poverty schools, but those schools were just as likely to report having at least some students involved in their programs. And so I think that's a really positive thing that we're not seeing some big inequity where really good policies are in one type of district and really bad policies in another type.

Michael Petrilli:

Yeah, no, that is good. So the other encouraging trend, once you look at the high school level, there's not surprisingly a lot going on around advanced education, a lot of advanced placement courses we know that has expanded dramatically in recent years, or international baccalaureate dual enrollment. There's less gatekeeping than there used to be perhaps at the high school level. But here's the thing is we identify kids for advanced ed or gifted ed early, like say maybe third or fourth grade, but then there's not much for them until they get to high school where they can take a bunch of AP classes. But it feels like in the middle when we're talking about elementary school offerings, even some middle school offerings kind of lame, right? Is that fair to say? Not a lot there.

Adam Tyner:

Yeah. I mean, I think this is one of those places where it's really a Rorschach test because part-time pullout classes are the most common type of service for elementary and middle school students. And that part-time pullout class, we all know that could be pretty high quality or it could be almost nothing. And so it's really, unfortunately, I think at future research with the knowledge that part-time pullout classes are so prevalent, we need to ask some even more detailed questions about what that means. But it really is disappointing that stuff like having a whole school or a whole program that's dedicated to those students is very rare in elementary and middle grades. That's right.

Michael Petrilli:

And things like ideas that have been around forever, like grade skipping or acceleration, just for a subject like letting a second grader who's amazing at math, take third grade math even just for that hour a day, go move up to be with the third graders or take a group of kids who are ready to cover maybe fourth and fifth and sixth grade math over the course of two years instead of three. That sort of thing. Still not super prevalent. David, as you're listening to this, any thoughts or questions you got for Adam?

David Griffith:

Yeah, I don't think I'm too surprised by any of it. I think what stands out to me, like you guys are saying, is kind of I guess the inherent complexity of the solutions, right? Because a whole long list of things that schools, districts, teachers might do, and yeah, I'm with you guys. I think pullout certainly my experiences with it were mixed and I think it probably means something very different depending on what the resources the school is able to bring to bear. I don't have a whole lot to add guys, except that this is increasingly personal to me as my kids move through the education system here in dc found out last month that in the wake of the pandemic, the goal for kids in DC is for them to be able to count to 10 by the time they enter kindergarten. Now, some kids can count higher than that without saying anything about national norms or local norms. I'm just going to assert that some kids can count higher than that and

Michael Petrilli:

You can be very proud of your son. Who can,

David Griffith:

I'm very proud of my son. I'm not even, look, I'm not even talking about him. I just think in general, some kids can count higher than that, even in DC. And I mean, we can talk about how low that expectation is, but it should be just to try to make it real to people. It is frustrating if that's the standard, right? You don't have to be Einstein really to exceed it. And there has to be some sort of plan, right? For continuing to push kids. The goal cannot be, the sort of attitude cannot be that nobody moves forward. Nobody gets to 11 until everybody can get to 10. That's crazy. So anyway, that is my only comment. It's not hypothetical, right? And I don't think it's just about the top 1% or the top 0.1%, right? It's potentially about a very large class of kids who may not be well-served if you have a sort of one size fits all approach.

Michael Petrilli:

And my sense is that there's been a lot of progress at the high school level. Again, left, right, and center. I mean, I see groups, education trust is one for example, that very much on the left, very much supportive of the idea of we should have lots of AP classes, dual enrollment, ib. It's not for everyone though. It's for more kids maybe than we used to have in the past. We should worry a lot about access and diversity in those courses. But we should have it right, even though it used to be that tracking. So-called tracking was not okay on the left. So that's changed, but there's still those same attitudes when it comes to my senses, middle school and certainly elementary school. And so what happens, we don't do enough to prepare kids, especially kids from low income backgrounds to succeed in those advanced placement courses. Once they get to high school, you got to start in kindergarten, and yet we're not doing enough when it comes to that. Alright, I will give myself the last word then. As I see David and Adam shaking their heads, Adam, hey, great job on this study. I know there's a ton of work to get districts fill out the survey and charter networks.

Adam Tyner:

It was, and I didn't do it all myself either. There were a lot of Fordham colleagues who were calling up people in random parts of the country and blasting them with emails and pestering 'em to get them to answer our surveys. So a lot of credit around the whole office.

Michael Petrilli:

Alright, so again, check it out on our website, the Broken Pipeline advanced education policies at the local level. Adam, thanks for coming on. Hope to see you again on time soon.

Adam Tyner:

Alright, thanks guys.

Michael Petrilli:

Alright, now it's time for everyone's favorite Amber's Research minute. Hey Amber, welcome back to the show.

Amber Northern:

Thanks, Mike.

Michael Petrilli:

Hey, so yeah, the NFL draft give you some hope for your Washington commanders.

Amber Northern:

Oh my gosh, I missed it. Mike, did we get a bunch of good players?

Michael Petrilli:

You got the number two quarterback and I'm going to forget his name.

Amber Northern:

I've been a little bit out of it over the weekend. And what's this guy's name?

Michael Petrilli:

Oh my god, I'm going to forget. I'm terrible. See, I pretend. I try to pretend I'm all sporty. For our listeners here it was the LSU quarterback.

Amber Northern:

Alright, good. Well we need some talent on that team, I got to say.

Michael Petrilli:

Yeah. Does Major League Soccer do this sort of thing? David? Is this a big thing? They have a draft, yeah.

David Griffith:

Yes. You're so sporty, Mike. Yeah.

Michael Petrilli:

Is it nationally televised?

David Griffith:

I believe so. Whether anyone watches is another question.

Amber Northern:

Clearly we got to practice this lather beforehand.

Michael Petrilli:

Yeah, I guess I really should have looked up the guy's name. Jalen something. Alright, I'll look it up. While you're doing the research minute and which is a good segue, it is time for the research minute, what you got for us this week.

Amber Northern:

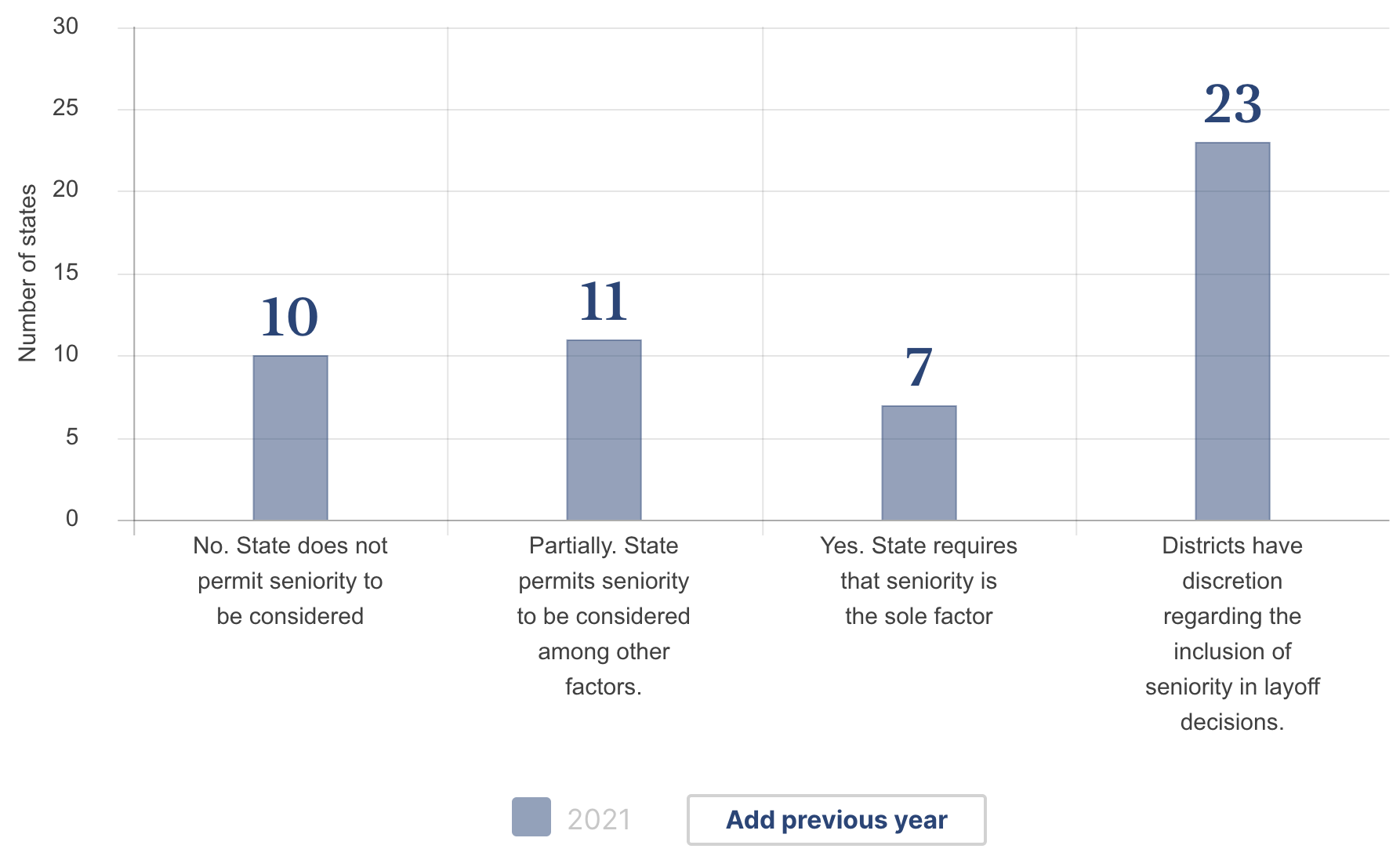

It's a new study out from NBER by Rick EK and two other economists that attempt to evaluate the impact of moving from NCLB to essa, at least, I'll just say the impact of one part of it, which are the actions that states took to change personnel policies for teachers with the added flexibility that they then had under essa. So they break teacher policies into input and output based policies using data from NCTQ. Output based policies relate to teacher accountability included in NCLB, but that were relaxed in essa. These include the use of student growth measures and teacher evaluations, whether state legislation explicitly indicates that districts are required to evaluate all teachers each year, whether states can use instructional ineffectiveness as grounds for dismissal, and whether legislation requires effectiveness to be considered when making teacher layoffs. So those are all output based. Then they've got another set of input based teacher policies that were unchanged and they act as the control policies to what would've happened in the absence of the change federal laws.

So the second set, again, unchanged input related elements, not directly related to student achievement outcomes, but that affect the teacher labor market. So these are things like compensation for advanced degrees, higher pay, if you teach in a high needs school loan forgiveness for teaching in a high needs school. The various policies are related directly to the provisions of NCLB and essa. So they look at the state changes in those policies that coincide with the move from NCLB to essa. And of note ESSA gave development of teacher evaluations and teacher policies back to the states. So they're saying that's really integral to what they're trying to measure here.

Michael Petrilli:

Now. Okay, but let me just pause for a moment here because I'm scratching my head. I'm thinking what? Alright, I mean, for example, no Child Left Behind did not, I don't think, say anything about teacher evaluations, right? That came later. That was in Race to the top. Well

Amber Northern:

They did, I'm sorry. They also put race to the top in with NCLB, but I'm just saying NCLB versus NCLB race to the top every time.

Michael Petrilli:

Okay. Alright, fair enough. So that's important. Alright. And some of this other stuff though still, I'm like really, I don't know that it's all that related to federal policy one way or the other.

Amber Northern:

Well, or that it's all that clean in terms of an input versus an output. But I do agree that the outputs are more related to student achievement than the inputs. Okay. So the treatment, again, it's complicated, but the treatment is the relaxation of the federal rules or a change in the locus of decision making. They make a point to say it's not about all these specific plans and regulations and laws, that all those things are mediating factors that affect the student outcomes that result from the change in federalism. So they relate these various teacher policies to growth and student achievement across states. So then they go to NA and they say, okay, well NAP doesn't provide longitudinal data for individual students, but it has representative data for the student populations of each state at different times from 1990 to 2019. They construct a measure of average achievement growth in each state by comparing grade four scores and math or reading to grade eight scores four years later with these various controls that are available to them. So they're following the same cohort in each state. And then the analysis again focuses on two cohort students in each state in grade eight in 2015, and then in 2019, and they're looking at achievement growth for the cohort and school at the end of NCLB and for the cohort at the beginning of essa. Alright, I think that's the main thing you need to know.

Michael Petrilli:

So wait, the cohort goes, okay, wait, basically 2015 to 2019 from when they were fourth grade going to

Amber Northern:

Eighth grade. Eighth grade, yes. They follow that, those two cohorts. That's right. Alright. And then they use prior achievement so they can measure the depreciation or the growth of achievement between the end of NCLB in the beginning of essa. Alright, I got to get to the findings. We could be forever on the methods. Given the change in decision-making from federal to state government states tended to pull away from the NCLB output based policies. No surprise there when they link the teacher accountability changes to state growth and student achievement measured by these changes in NAP scores between fourth and eighth grade, which I just told you about. They find that the strong output-based teacher policies are associated with greater student achievement gains in both math and reading. On the other hand, these input based policies are associated with lower state achievement gains, but when they combine the two, they find that the shift in federalism inherent in ESSA was associated with a small but significant fall in student achievement.

They estimate that going from no such policies to having all of these identified policies implies an increase in growth of 0.2 standard deviation in math to 0.3 standard deviation in reading. But then they argue that these estimates, this is just the immediate impact that maybe it's going to be worse. These responses as over time they say, Hey, we don't know what covid did. Covid may have made things worse. And besides, we know this is small potatoes, but we're also looking at a national policy that impacts millions of public school students. So that's what I've got.

Michael Petrilli:

Okay. I'm really, this is a head scratcher here

Amber Northern:

And it's hefty. It's hefty. So

Michael Petrilli:

I mean it, is it fair to say that, I mean, one piece of this sounds pretty intuitive to me, which is states that let's say, kept their teacher evaluation policies, I don't know, Tennessee and the District of Columbia, I could buy that maybe they did better. I think in this trend it's sort of making at least staying steady, whereas a lot of these states were, I think losing ground in this time as we started to see a slump even before the great recession. But okay, so if you kept something like teacher, I mean, is it basically teacher eval? Is that basically what they're

Amber Northern:

Looking at? Well, let me look. It is teacher, they were very specific about the output. You had to use student growth in your teacher eval. You had to say that districts are required to evaluate all teachers, and you had to say that instructional ineffective was grounds for dismissal and you had to consider teacher effectiveness when you considered making layoffs.

Michael Petrilli:

So all that stuff that states, in some cases adopted under race to the top and then quietly or not let go of as that ended and as there was a huge political backlash to teacher valuation and it seemed like in most places it was not done very well and didn't have much of an impact. Again, I guess this was somewhat related to federal policy, but I dunno. David, what do you think? Is this really about federal policy and federalism?

David Griffith:

I guess I'm sort of curious to know if they characterize the states that backed away from, we'll call it accountability just for simplicity's sake, if they characterize them in any other way. Are these red states because they don't like top down accountability? Are they blue states because the teachers unions quad back, whatever it is they wanted to call back. What states are these?

Amber Northern:

They're not categorized. David,

David Griffith:

I mean, I'm a little torn because on the one hand I basically buy the conclusion and the theory of action here. But on the other hand, there's a whole lot going on. And the million dollar question is like, are the states that are selecting into less accountability? Are they different in some other way? Were they already going to be seeing declining achievement for some other reason? And that's strikes me as a very difficult question to answer. I have not read the study in detail, so it's not intended as a critique, but it strikes me as a high bar

Michael Petrilli:

And look, all the research and following of teacher eval that we did, I feel like we knew that it was not very effective in most places. And so a lot of these places they gave up on it. I'm not sure they gave up on anything that was working anyways. And whether, I mean, I get it that they were trying to look at any growth patterns ahead of time, but I'm not sure they could have picked up on that. I don't remember any state which was really kind hardcore, we're actually going to do this. We're actually going to evaluate teachers in this tough way. Were actually going to have a chance of laying teachers off. I feel like it was just Tennessee and DC was basically it at the state level, and they kept their systems, otherwise, these other states that gave up on 'em were all BS anyways.

Amber Northern:

Right. You're saying they weren't differentiating them anyway. They

Michael Petrilli:

Went through the motions. They followed the federal guidance. But we knew that the districts, the states might've had policies, but the districts didn't follow them. The action was at the district level and the districts maybe went through the emotions and it was a mess. And so I don't know this idea that it was, if only we had a federal policy saying, you still have to do that thing that we quote call teacher eval, and we would've had better impacts in these other states. It's only because Tennessee and DC did it. Well, I'm assuming these are the main places that we're seeing much by way of impact.

David Griffith:

I mean, to me, the question is really what is the sustainable, politically sustainable version of accountability here that we're after? You can scream into the hurricane all you want about, oh, let's bring back no child left behind. I don't really think we should, to be honest. But the more important point is we can't. Right? It's not going to happen. And I mean, I feel like for me, it's tough to disentangle the effects of these things from the sort of short-term nature of them. Yeah. If you scare the heck out of people for a couple of years and you think they're going to close their schools and fire all the teachers, yeah, you'll see an effect. But if it's got the sort of seeds of its own destruction built into it, then it's not much of a plan. And so what we really need is accountability that will still be here a decade from now. That's the best form of accountability. And I'm not sure I can articulate exactly what that looks like, but you could make the case that the move to a sort of Ian move to state accountability is a better platform for getting there than NCLB. So in that sense,

Michael Petrilli:

Well, and if you're talking about teacher accountability, look, I think honestly, I think we know there's not much you can write into federal law and there may not be a lot you can write into state law. Yes. Some of these state policies, if you mandate last in first out, if you make it impossible for districts to hold teachers accountable, those things can matter. But even if you permit districts to be tough on teacher accountability, I think it's hard to mandate that they be tough on teacher accountability. And so it's at the local level, that's where the action is. But we don't have data very many local places.

Amber Northern:

And by the way, it's really hard. It's a really hard sell to make with the shortages we're seeing in some places and the overall discontent we're hearing anecdotally from the teaching workforce. So,

Michael Petrilli:

All right. Well, so much more. We could unpack this to be continued. This topic is not going away. Tim Daley's been writing great stuff for the education Gad Fly in our Fly paper blog in his blog about the history of teacher EVI that is worth checking out as well as it seems quite relevant here. But thank you Amber. Good

Amber Northern:

Stuff. Yes, indeed.

Michael Petrilli:

Alright, well that is all the time we've got for this week. So until next week,

David Griffith:

I'm David Griffith.

Michael Petrilli:

And I'm Mike Petrolli, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, signing off.