The Nation’s Report Card: Writing 2011

No more pencils

Traditionalists cringe, tech buffs rejoice: This latest NAEP writing assessment for grades eight and twelve marks the first computer-based appraisal (by the “nation’s report card”) of student proficiency in this subject. It evaluates students’ writing skills (what NAEP calls both academic and workplace writing) based on three criteria: idea development, organization, and language facility and conventions. Results were predictably bad: Just twenty-four percent of eighth graders and 27 percent of twelfth graders scored proficient or above. Boys performed particularly poorly; half as many eighth-grade males reached proficiency as their female counterparts. The use of computers adds a level of complexity to these analyses: The software allows those being tested to use a thesaurus (which 29 percent of eighth graders exploited), text-to-speech software (71 percent of eighth graders used), spell check (three-quarters of twelfth graders), and kindred functions. It is unclear whether use of these crutches affected a student’s “language facility” scores, though it sure seems likely. While this new mechanism for assessing kids’ writing prowess makes it impossible to track trend data, one can make (disheartening) comparisons across subjects. About a third of eighth graders hit the NAEP proficiency benchmark in the latest science, math, and reading assessments, compared to a quarter for writing. So where to go from here? The report also notes that twelfth-grade students who write four to five pages a week score ten points higher than those who write just one page a week. Encouraging students to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) is a start.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Writing 2011 (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, 2012)

With so much attention focused on teachers (from hiring to evaluation to pay to firing), not enough has been paid to public education’s other vital human resource: school principals. And that’s a problem. “Unfortunately, when it comes to cultivating school leaders, current state-level practices are, at best, haphazard,” write authors Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross in this Center for Reinventing Public Education brief. Their recommendations are sound and straightforward: States should track the right data (anticipate when principals will retire, which ones need more support, and which training programs produce the best results) and strategically fill the leader pipeline (giving the right work to the right people in the right schools). Putting flesh on those policy bones, the brief provides specific examples of where individual states should target efforts. Iowa, for example, should employ principal-recruitment strategies because of the number of leaders nearing retirement age, while Indiana—with a younger principal population—should emphasize professional development. Getting teacher policy right is key. But so is principal policy. This brief offers a smart way forward.

With so much attention focused on teachers (from hiring to evaluation to pay to firing), not enough has been paid to public education’s other vital human resource: school principals. And that’s a problem. “Unfortunately, when it comes to cultivating school leaders, current state-level practices are, at best, haphazard,” write authors Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross in this Center for Reinventing Public Education brief. Their recommendations are sound and straightforward: States should track the right data (anticipate when principals will retire, which ones need more support, and which training programs produce the best results) and strategically fill the leader pipeline (giving the right work to the right people in the right schools). Putting flesh on those policy bones, the brief provides specific examples of where individual states should target efforts. Iowa, for example, should employ principal-recruitment strategies because of the number of leaders nearing retirement age, while Indiana—with a younger principal population—should emphasize professional development. Getting teacher policy right is key. But so is principal policy. This brief offers a smart way forward.

SOURCE: Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross, Principal Concerns: Leadership Data and Strategies for States (Seattle, Washington: Center on Reinventing Public Education, September 2012).

The winds of accountability have closed the doors of some failing schools. But most stay open, struggling (often unsuccessfully) to boost student achievement. Michael Brick’s Saving the School tells the story of Austin’s Reagan High, a school that did weather the storm and improve. The book is structured as a narrative that follows a few main characters: the principal, a young science teacher, the basketball coach, and a star student athlete. Through schmaltzy prose, one can glimpse some worthy policy guidance. Above all: Hire a driven, mission-oriented, and strong leader, then inject classrooms with teachers of the same ilk. At Reagan, the principal scoured the neighborhood to locate truants. The science teacher opened her home to her students for Bible study, free meals, and a sympathetic ear. The coach’s deep and enduring connection to his team helped revive the school’s flagging spirit. And the students responded. Brick forces readers to think about teacher quality and its enormous effect on students, especially those who struggle, and he reminds us of the power of expectations. The most concrete lesson of the book, an important message in and of itself, is that when policy hits practice, things get complicated.

SOURCE: Michael Brick, Saving the School: The True Story of a Principal, a Teacher, a Coach, a Bunch of Kids, and a Year in the Crosshairs of Education Reform (New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2012).

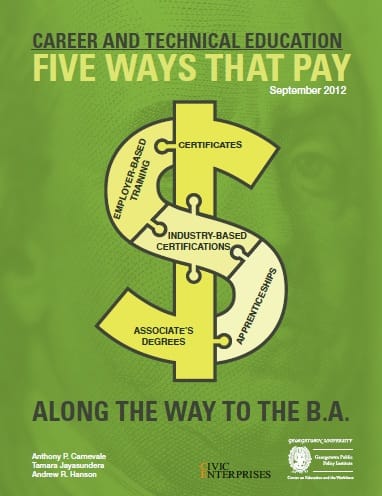

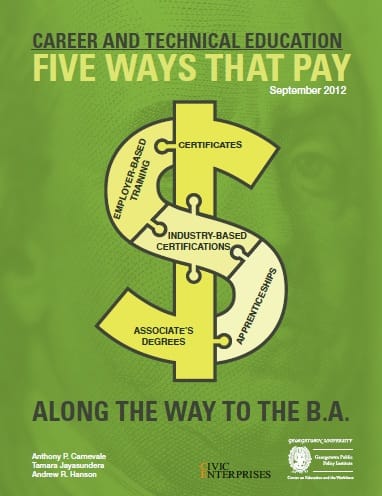

At 31 percent, the United States currently ranks second among OECD nations—behind Norway—for the percentage of its workforce with a four-year college education. That’s the good news. The bad news is that we rank sixteenth for the percentage of our workforce with a sub-baccalaureate education (think: postsecondary and industry-based certificates, associate’s degrees). Yet a swath of jobs in America calls for just that sort of preparation, which often begins in high school. Dubbed “middle jobs” in this report by the Center on Education and the Workforce, these employment opportunities pay at least $35,000 a year and are divided among white- and blue-collar work. Yet they are largely ignored in our era of “college for all.” In two parts, this report delineates five major categories of career and technical education (CTE), then lists specific occupations that require this type of education. It’s full of facts and figures and an excellent resource for those looking to expand rigorous CTE in the U.S. Most importantly, it presents this imperative: Collect data on students who emerge from these programs. By tracking their job placements and wage earnings, we can begin to rate CTE programs, shutter those that are ineffective, and scale up those that are successful. If CTE is ever to gain traction in the U.S.—and shed the stigma of being low-level voc-tech education for kids who can’t quite make it academically—this will be a necessary first step.

At 31 percent, the United States currently ranks second among OECD nations—behind Norway—for the percentage of its workforce with a four-year college education. That’s the good news. The bad news is that we rank sixteenth for the percentage of our workforce with a sub-baccalaureate education (think: postsecondary and industry-based certificates, associate’s degrees). Yet a swath of jobs in America calls for just that sort of preparation, which often begins in high school. Dubbed “middle jobs” in this report by the Center on Education and the Workforce, these employment opportunities pay at least $35,000 a year and are divided among white- and blue-collar work. Yet they are largely ignored in our era of “college for all.” In two parts, this report delineates five major categories of career and technical education (CTE), then lists specific occupations that require this type of education. It’s full of facts and figures and an excellent resource for those looking to expand rigorous CTE in the U.S. Most importantly, it presents this imperative: Collect data on students who emerge from these programs. By tracking their job placements and wage earnings, we can begin to rate CTE programs, shutter those that are ineffective, and scale up those that are successful. If CTE is ever to gain traction in the U.S.—and shed the stigma of being low-level voc-tech education for kids who can’t quite make it academically—this will be a necessary first step.

SOURCE: Anthony P. Carnevale, Tamara Jayasundera, Andrew R. Hanson, Career and Technical Education: Five Ways that Pay Along the Way to the B.A. (Washington, D.C.: Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University, September 2012).

Checker and Mike autopsy the Chicago teachers’ strike and wonder why students at top schools have the cheating bug. Amber looks at why kids jst cn’t seam to rite.

National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Writing 2011 (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, 2012).

In an educational climate consumed with leaving no child behind and closing achievement gaps, America's highest performing and most promising students have too often been neglected. Our nation's persistent inability to cultivate our high-potential youth—especially tomorrow's leaders in science, technology, entrepreneurship, and other sectors that bear on our long-term prosperity and well-being—poses a critical threat to American competitiveness. EXAM SCHOOLS: Inside America's Most Selective Public High Schools, by Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Jessica A. Hockett, presents a pioneering examination of our nation's most esteemed and selective public high schools—academic institutions committed exclusively to preparing America's best and brightest for college and beyond.

Like Exam Schools on Facebook

Buy Exam Schools from Amazon

Buy Exam Schools from Princeton University Press

Barack Obama and Mitt Romney both attended elite private high schools. Both are undeniably smart and well educated and owe much of their success to the strong foundation laid by excellent schools.

Every motivated, high-potential young American deserves a similar opportunity. But the majority of very smart kids lack the wherewithal to enroll in rigorous private schools. They depend on public education to prepare them for life. Yet that system is failing to create enough opportunities for hundreds of thousands of these high-potential girls and boys.

Mostly, the system ignores them, with policies and budget priorities that concentrate on raising the floor under low-achieving students. A good and necessary thing to do, yes, but we’ve failed to raise the ceiling for those already well above the floor.

Public education’s neglect of high-ability students doesn’t just deny individuals opportunities they deserve. It also imperils the country’s future supply of scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs.

Today’s systemic failure takes three forms.

First, we’re weak at identifying “gifted and talented” children early, particularly if they’re poor or members of minority groups or don’t have savvy, pushy parents.

Second, at the primary and middle-school levels, we don’t have enough gifted-education classrooms (with suitable teachers and curriculums) to serve even the existing demand. Congress has “zero-funded” the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Program, Washington’s sole effort to encourage such education. Faced with budget crunches and federal pressure to turn around awful schools, many districts are cutting their advanced classes as well as art and music.

Third, many high schools have just a smattering of honors or Advanced Placement classes, sometimes populated by kids who are bright but not truly prepared to succeed in them.

For more on this issue, purchase Exam Schools: Inside America's Most Selective Public High Schools. |

Here and there, however, entire public schools focus exclusively on high-ability, highly motivated students. Some are nationally famous (Boston Latin, Bronx Science), others known mainly in their own communities (Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills, Austin’s Liberal Arts and Science Academy). When my colleague Jessica A. Hockett and I went searching for schools like these to study, we discovered that no one had ever fully mapped this terrain.

In a country with more than 20,000 public high schools, we found just 165 of these schools, known as exam schools. They educate about 1 percent of students. Nineteen states have none. Only three big cities have more than five such schools (Los Angeles has zero). Almost all have far more qualified applicants than they can accommodate. Hence they practice very selective admission, turning away thousands of students who could benefit from what they have to offer. Northern Virginia’s acclaimed Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, for example, gets some 3,300 applicants a year—two-thirds of them academically qualified—for 480 places.

We built a list, surveyed the principals and visited eleven schools. We learned a lot. While the schools differ in many ways, their course offerings resemble A.P. classes in content and rigor; they have stellar college placement; and the best of them expose their pupils to independent study, challenging internships and individual research projects.

Critics call them elitist, but we found the opposite. These are great schools accessible to families who can’t afford private schooling or expensive suburbs. While exam schools in some cities don’t come close to reflecting the demographics around them, across the country the low-income enrollment in these schools parallels the high school population as a whole. African-American youngsters are “overrepresented” in them and Asian-Americans staggeringly so (21 percent versus 5 percent in high schools overall). Latinos are underrepresented, but so are whites.

That’s not so surprising. Prosperous, educated parents can access multiple options for their able daughters and sons. Elite private schools are still out there. So are New Trier, Scarsdale and Beverly Hills. The schools we studied, by and large, are educational oases for families with smart kids but few alternatives.

They’re safe havens, too—schools where everyone focuses on teaching and learning, not maintaining order. They have sports teams, but their orchestras are better. Yes, some have had to crack down on cheating, but in these schools it’s O.K. to be a nerd. You’re surrounded by kids like you—some smarter than you—and taught by capable teachers who welcome the challenge, teachers more apt to have Ph.D.’s or experience at the college level than high school instructors elsewhere. You aren’t searched for weapons at the door. And you’re pretty sure to graduate and go on to a good college.

Many more students could benefit from schools like these—and the numbers would multiply if our education system did right by such students in the early grades. But that will happen only when we acknowledge that leaving no child behind means paying as much attention to those who’ve mastered the basics—and have the capacity and motivation for much more—as we do to those who cannot yet read or subtract.

It’s time to end the bias against gifted and talented education and quit assuming that every school must be all things to all students, a simplistic formula that ends up neglecting all sorts of girls and boys, many of them poor and minority, who would benefit more from specialized public schools. America should have a thousand or more high schools for able students, not 165, and elementary and middle schools that spot and prepare their future pupils.

With their support for school choice, Mr. Romney and Mr. Obama have both edged toward recognizing that kids aren’t all the same and schools shouldn’t be, either. Yet fear of seeming elitist will most likely keep them from proposing more exam schools. Which is ironic and sad, considering where they went to school. Smart kids shouldn’t have to go to private schools or get turned away from Bronx Science or Thomas Jefferson simply because there’s no room for them.

A version of this post appeared as an op-ed in the September 19, 2012 edition of the New York Times.

The media blitz surrounding a certain other education story overshadowed a recent court decision in Madison, Wisconsin with potentially far-reaching consequences. Last Friday, a judge in Dane County did what tens of thousands of protestors who swarmed the state capital in the spring of 2011 couldn’t: torpedo the law that significantly restricted public-employee-bargaining rights in the Badger State. The fallout from Judge Juan Colas’s decision to strike down portions of Act 10, Governor Scott Walker’s signature legislative accomplishment, on grounds that the law violated workers’ constitutional rights could be devastating on several fronts. In the short term, the ruling rips the scab off one of the uglier reform fights in recent memory and threatens to toss the state’s labor relations into disarray as unions scramble to redo the refreshingly sane contracts negotiated after the law’s passage—deals that have already saved districts boatloads of money. Even if Wisconsin’s attorney general succeeds in preserving the law pending the outcome of an appeal (the conservative-leaning state supreme court is apt to be more sympathetic than a liberal Madison judge), education-reform advocates all over need to keep an eye on the proceedings. The late unpleasantness in Chicago reaffirms how much public-employee collective bargaining handcuffs even the most ambitious government leaders. Losing hard-fought ground in Wisconsin just as its new law begins to pay dividends would be a far greater setback than the CTU’s win in Chicago.

RELATED ARTICLE: “Wisconsin Collective Bargaining Ruling Causes Confusion,” by Scott Bauer, The Associated Press, September 17, 2012.

In a few weeks, the Los Angeles school board will discuss enacting a moratorium on new charter schools, a measure that one board member claims is necessary to better assess the quality of a sector that now enrolls 15 percent of L.A. pupils. Not only would such a moratorium flout the law—school boards can’t simply set aside their legal obligation to consider charter applications—it would be an irresponsible way to manage charter-school quality. The board should be weeding out bad charters, both extant and prospective, but that’s only half of the job of a charter-school authorizer (and a difficult job at that). The board would be more effective—and more convincing when they say they care about charter students—if they made the effort to find new and promising providers to replace the failures. But, as with many moves like this, school-board members here seem intent on slowing the growth of charters by artificially capping enrollment (the wait list for L.A. charters is presently about 10,000). The board tried unsuccessfully to impose a moratorium on charters six years ago, just as the city became the first in the United States to contain 100 such schools, and it has become more antagonistic ever since. Not good for kids. Not good for education. But further evidence that the kids’ interest doesn’t necessarily prevail on the “management” side of the bargaining table, either. Then again, Los Angeles is one of those sad cases where that table seems to have just one side.

RELATED ARTICLE: “Parents decry proposed crackdown on LA charters,” by Christina Hoag, The Associated Press, September 11, 2012.

Sunday’s surprise move by the Chicago Teachers Union to keep kids locked out of class for an extra two days as delegates deliberated over a contract they would soon accept seemed gratuitous at the time, adding insult to the injuries that Rahm Emanuel’s tough-guy reputation had already sustained. Reports of a mild insurrection within union ranks offer another interpretation, however, and serve as an important reminder not to underestimate the different priorities and motivations at work in internal union politics.

Sunday’s surprise move by the Chicago Teachers Union to keep kids locked out of class for an extra two days as delegates deliberated over a contract they would soon accept seemed gratuitous at the time, adding insult to the injuries that Rahm Emanuel’s tough-guy reputation had already sustained. Reports of a mild insurrection within union ranks offer another interpretation, however, and serve as an important reminder not to underestimate the different priorities and motivations at work in internal union politics.

Just when it looked like the education Super Bowl had left town, Chicago’s next education crisis reared its head: The city’s teacher-pension system—like most such funds—is in a sorry state, with $10 billion in assets and $1 billion a year flowing out the door to retirees, far more than is being taken in. The situation makes the fight over 16 percent raises seem quaint…and the odds of a sane resolution to the pension problem seem downright chilling in comparison.

Columnist Eugene Robinson argued that “teachers are being saddled with absurdly high expectations" because poverty influences achievement far more than instruction. If only proponents of revamped teacher evaluations would acknowledge this and support evaluation models that measure what a teacher contributes to student learning rather a single fixed bar that all students are held to. What would they call it? Value-increased? No…Value-boosted? Hmmm. Anyone?

Chicago’s more than 350,000 public school pupils finally went back to class yesterday, after seven missed days due to the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike. They were thus deprived of about four percent of the school year—and these are kids who need more schooling, not less. (One big issue in the labor-management dispute was Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s plan to lengthen Chicago’s famously bobtailed school day and year.)

The Chicago strike was a useful reminder that teacher unions are fundamentally selfish. Photo by RachelD. |

Thanks a bunch, CTU.

This strike—the first big one by teachers in ages—will be examined every which way for months to come, and the contract that was finally agreed upon will be carefully autopsied. (If you’d like to see a careful analysis of a previous Chicago teacher contract, download Fordham’s Leadership Limbo report and flip to page fifty. If you’d like to inspect the contract that was in force until a couple of months ago—be warned that it’s 176 pages long!—you can access it from the National Council on Teacher Quality’s website.)

As for the new contract, my friends at NCTQ are more bullish than I am. Rick Hess’s take seems closer to the mark. Yes, it contains a handful of features from Rahm’s reform shopping list. But every one of them was weakened, diluted, deferred, or made very expensive for a city that can ill afford the added cost.

Here is what the CTU said to its own members in advance of Tuesday’s ratification vote:

And here’s what AFT president Randi Weingarten said in hailing the ratification:

But of course that’s precisely what this episode did not demonstrate. What it demonstrated was that what teacher unions care about has practically nothing to do with what’s good for the kids and everything to do with what teachers want for themselves. They are fundamentally selfish.

You can say that’s what unions exist to do. I don’t know for sure if the late Albert Shanker actualy did declare that “when kids vote in union elections, that’s when I’ll worry about them” or words to that effect. But yes, it’s a fact that unions look after their members.

Let them then not pretend otherwise, despite all this talk by Randi Weingarten and Karen Lewis about the new CTU contract being in the best interest of Chicago’s schoolchildren. It’s not. Rahm’s original proposals were—and were more affordable, to boot.

We’ve seen a few instances in recent years of labor unions eventually realizing that the health of their industry and the quality of its products actually bear, in the long run, on their own jobs and well-being. The United Auto Workers eventually figured that out with regard to the U.S. auto industry. But not until Detroit’s “Big Three” were collapsing. And other major industries actually did collapse—“Big Steel,” for instance—in large part because their unions never got the message that it was bad for them to have those jobs move to Korea or Brazil.

Other industries—look at the airlines—have to declare bankruptcy in order to get out from under labor contracts that are, in fact, helping to bankrupt them. That’s because their unions were (and are), like the CTU, attending only to the interests, priorities, and preferences of the employees who belong to them.

By week two of the Chicago strike, I suspect, residents of the Windy City were figuring this out. At the outset, they tended to blame Rahm, not the CTU, for the walkout. But when a compromise was struck by district and union representatives—a compromise, I repeat, that is about the employees’ interests, not the kids’ or the taxpayers’—and the union still continued to strike for two utterly unnecessary days, Chicago’s parents and voters must have realized that this was indeed about selfish employees, not provocative mayors.

And that, I believe, is the principle long-term good that may come out of this for the country as a whole. Whitney Tilson got it right when he commented the other day that

Let’s hope he’s right. Then let’s make the most of it.

In an educational climate consumed with leaving no child behind and closing achievement gaps, America's highest performing and most promising students have too often been neglected. Our nation's persistent inability to cultivate our high-potential youth—especially tomorrow's leaders in science, technology, entrepreneurship, and other sectors that bear on our long-term prosperity and well-being—poses a critical threat to American competitiveness. EXAM SCHOOLS: Inside America's Most Selective Public High Schools, by Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Jessica A. Hockett, presents a pioneering examination of our nation's most esteemed and selective public high schools—academic institutions committed exclusively to preparing America's best and brightest for college and beyond.

Like Exam Schools on Facebook

Buy Exam Schools from Amazon

Buy Exam Schools from Princeton University Press

In an educational climate consumed with leaving no child behind and closing achievement gaps, America's highest performing and most promising students have too often been neglected. Our nation's persistent inability to cultivate our high-potential youth—especially tomorrow's leaders in science, technology, entrepreneurship, and other sectors that bear on our long-term prosperity and well-being—poses a critical threat to American competitiveness. EXAM SCHOOLS: Inside America's Most Selective Public High Schools, by Chester E. Finn, Jr. and Jessica A. Hockett, presents a pioneering examination of our nation's most esteemed and selective public high schools—academic institutions committed exclusively to preparing America's best and brightest for college and beyond.

Like Exam Schools on Facebook

Buy Exam Schools from Amazon

Buy Exam Schools from Princeton University Press

Traditionalists cringe, tech buffs rejoice: This latest NAEP writing assessment for grades eight and twelve marks the first computer-based appraisal (by the “nation’s report card”) of student proficiency in this subject. It evaluates students’ writing skills (what NAEP calls both academic and workplace writing) based on three criteria: idea development, organization, and language facility and conventions. Results were predictably bad: Just twenty-four percent of eighth graders and 27 percent of twelfth graders scored proficient or above. Boys performed particularly poorly; half as many eighth-grade males reached proficiency as their female counterparts. The use of computers adds a level of complexity to these analyses: The software allows those being tested to use a thesaurus (which 29 percent of eighth graders exploited), text-to-speech software (71 percent of eighth graders used), spell check (three-quarters of twelfth graders), and kindred functions. It is unclear whether use of these crutches affected a student’s “language facility” scores, though it sure seems likely. While this new mechanism for assessing kids’ writing prowess makes it impossible to track trend data, one can make (disheartening) comparisons across subjects. About a third of eighth graders hit the NAEP proficiency benchmark in the latest science, math, and reading assessments, compared to a quarter for writing. So where to go from here? The report also notes that twelfth-grade students who write four to five pages a week score ten points higher than those who write just one page a week. Encouraging students to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) is a start.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Writing 2011 (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, 2012)

With so much attention focused on teachers (from hiring to evaluation to pay to firing), not enough has been paid to public education’s other vital human resource: school principals. And that’s a problem. “Unfortunately, when it comes to cultivating school leaders, current state-level practices are, at best, haphazard,” write authors Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross in this Center for Reinventing Public Education brief. Their recommendations are sound and straightforward: States should track the right data (anticipate when principals will retire, which ones need more support, and which training programs produce the best results) and strategically fill the leader pipeline (giving the right work to the right people in the right schools). Putting flesh on those policy bones, the brief provides specific examples of where individual states should target efforts. Iowa, for example, should employ principal-recruitment strategies because of the number of leaders nearing retirement age, while Indiana—with a younger principal population—should emphasize professional development. Getting teacher policy right is key. But so is principal policy. This brief offers a smart way forward.

With so much attention focused on teachers (from hiring to evaluation to pay to firing), not enough has been paid to public education’s other vital human resource: school principals. And that’s a problem. “Unfortunately, when it comes to cultivating school leaders, current state-level practices are, at best, haphazard,” write authors Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross in this Center for Reinventing Public Education brief. Their recommendations are sound and straightforward: States should track the right data (anticipate when principals will retire, which ones need more support, and which training programs produce the best results) and strategically fill the leader pipeline (giving the right work to the right people in the right schools). Putting flesh on those policy bones, the brief provides specific examples of where individual states should target efforts. Iowa, for example, should employ principal-recruitment strategies because of the number of leaders nearing retirement age, while Indiana—with a younger principal population—should emphasize professional development. Getting teacher policy right is key. But so is principal policy. This brief offers a smart way forward.

SOURCE: Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross, Principal Concerns: Leadership Data and Strategies for States (Seattle, Washington: Center on Reinventing Public Education, September 2012).

The winds of accountability have closed the doors of some failing schools. But most stay open, struggling (often unsuccessfully) to boost student achievement. Michael Brick’s Saving the School tells the story of Austin’s Reagan High, a school that did weather the storm and improve. The book is structured as a narrative that follows a few main characters: the principal, a young science teacher, the basketball coach, and a star student athlete. Through schmaltzy prose, one can glimpse some worthy policy guidance. Above all: Hire a driven, mission-oriented, and strong leader, then inject classrooms with teachers of the same ilk. At Reagan, the principal scoured the neighborhood to locate truants. The science teacher opened her home to her students for Bible study, free meals, and a sympathetic ear. The coach’s deep and enduring connection to his team helped revive the school’s flagging spirit. And the students responded. Brick forces readers to think about teacher quality and its enormous effect on students, especially those who struggle, and he reminds us of the power of expectations. The most concrete lesson of the book, an important message in and of itself, is that when policy hits practice, things get complicated.

SOURCE: Michael Brick, Saving the School: The True Story of a Principal, a Teacher, a Coach, a Bunch of Kids, and a Year in the Crosshairs of Education Reform (New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2012).

At 31 percent, the United States currently ranks second among OECD nations—behind Norway—for the percentage of its workforce with a four-year college education. That’s the good news. The bad news is that we rank sixteenth for the percentage of our workforce with a sub-baccalaureate education (think: postsecondary and industry-based certificates, associate’s degrees). Yet a swath of jobs in America calls for just that sort of preparation, which often begins in high school. Dubbed “middle jobs” in this report by the Center on Education and the Workforce, these employment opportunities pay at least $35,000 a year and are divided among white- and blue-collar work. Yet they are largely ignored in our era of “college for all.” In two parts, this report delineates five major categories of career and technical education (CTE), then lists specific occupations that require this type of education. It’s full of facts and figures and an excellent resource for those looking to expand rigorous CTE in the U.S. Most importantly, it presents this imperative: Collect data on students who emerge from these programs. By tracking their job placements and wage earnings, we can begin to rate CTE programs, shutter those that are ineffective, and scale up those that are successful. If CTE is ever to gain traction in the U.S.—and shed the stigma of being low-level voc-tech education for kids who can’t quite make it academically—this will be a necessary first step.

At 31 percent, the United States currently ranks second among OECD nations—behind Norway—for the percentage of its workforce with a four-year college education. That’s the good news. The bad news is that we rank sixteenth for the percentage of our workforce with a sub-baccalaureate education (think: postsecondary and industry-based certificates, associate’s degrees). Yet a swath of jobs in America calls for just that sort of preparation, which often begins in high school. Dubbed “middle jobs” in this report by the Center on Education and the Workforce, these employment opportunities pay at least $35,000 a year and are divided among white- and blue-collar work. Yet they are largely ignored in our era of “college for all.” In two parts, this report delineates five major categories of career and technical education (CTE), then lists specific occupations that require this type of education. It’s full of facts and figures and an excellent resource for those looking to expand rigorous CTE in the U.S. Most importantly, it presents this imperative: Collect data on students who emerge from these programs. By tracking their job placements and wage earnings, we can begin to rate CTE programs, shutter those that are ineffective, and scale up those that are successful. If CTE is ever to gain traction in the U.S.—and shed the stigma of being low-level voc-tech education for kids who can’t quite make it academically—this will be a necessary first step.

SOURCE: Anthony P. Carnevale, Tamara Jayasundera, Andrew R. Hanson, Career and Technical Education: Five Ways that Pay Along the Way to the B.A. (Washington, D.C.: Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University, September 2012).