Chicago’s troubled school district has made national headlines recently—from the mass resignation of its appointed school board, which opposed the mayor’s efforts to borrow nearly $300 million at ruinous rates to give the teachers union a sweetheart contract, to the likely ouster of the district’s superintendent. But the city has also become a powerful symbol in the brewing battles over rightsizing efforts in the face of declining enrollment and expiring federal pandemic aid.

A decade ago, Chicago closed approximately fifty schools, one of the largest consolidation efforts in recent memory, and the consequences continue to be disputed. Much of this debate engages in selective cherry-picking of data and misleading interpretations of the evidence, giving rise to confusion about what (if any) lessons district leaders across the country should learn from Chicago’s experience.

A recent article by Thomas Toch, director of Georgetown University think tank FutureEd, and Maureen Kelleher, a freelance writer and FutureEd's former editorial director, suffers from many of the same problems. To understand the many things the authors get wrong about Chicago—as well as the few points they get right—it is important to examine the most important claims in their piece.

Claim: School closures caused student achievement to decline

“Shuttering the schools didn’t improve academic outcomes for their students,” Toch and Kelleher wrote, noting that displaced students “had lower math scores for at least four years after transferring.”

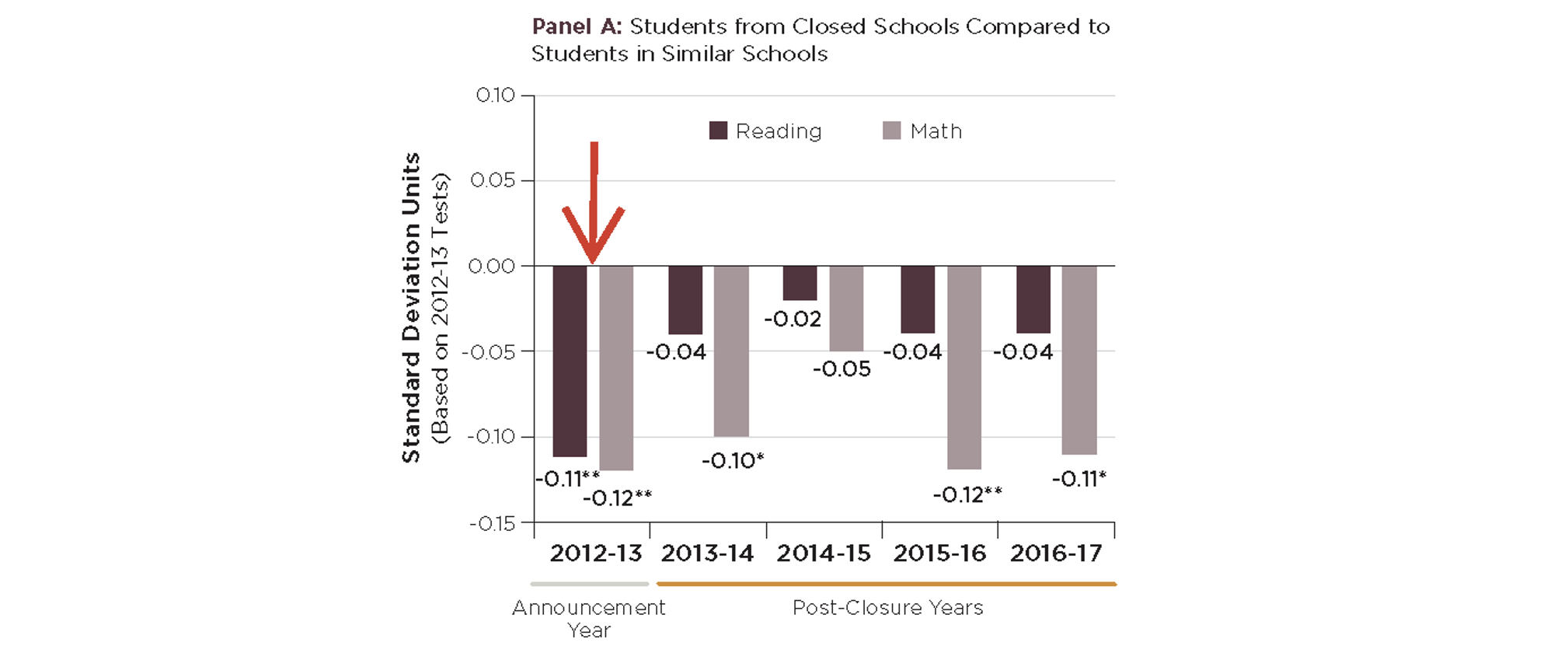

I’ve emphasized before that this is highly misleading. As the careful University of Chicago evaluation of Chicago’s closures showed, all the negative achievement impacts occurred in the year that planned consolidation was announced—before a single school had closed. This can be seen in the figure below, which is taken directly from the report. I’ve added a large red arrow over the announcement year, which corresponds to the test score drop.

The most likely explanation for the decline is the organized campaign to fight closures and the associated circus and psycho-drama that these efforts created. (This is also the reason the University of Chicago evaluation proposed to explain the increase in absenteeism that same year, speculating that “communities, schools, and families were advocating for their schools not to close” instead of making sure students were attending class.)

Interestingly, achievement began to rebound quickly once the buildings were actually shuttered and students moved to their new schools (although math scores dipped again a few years later). This pattern can be seen in the figure, with the negative effects shrinking in each of the first two post-closure years.

It would also be a huge mistake to draw strong conclusions about the impact of school closures on academic outcomes from Chicago alone. Studies in other cities that have closed a significant number of schools show that well-planned consolidation efforts can move the needle upward on learning.

In Newark, for example, students displaced by closure of their schools saw their achievement improve by between 10 percent and 15 percent of a standard deviation—sizable effects that researchers attributed to “reap[ing] the benefits of moving to higher value-added schools.” In New Orleans, closing low-performing district buildings and reopening them under charter management improved achievement even more. And a few weeks ago, a new study of the “portfolio” reform model in Denver found large gains by students forced to switch schools when theirs closed.

Claim: Closures pushed families to leave the district

Toch and Keller claim that school closures “contributed to the decline of the low-income Black neighborhoods where the schools were located,” citing an analysis published last year by the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ. That analysis, the authors assert, “found that Black neighborhoods that experienced a permanent school closure in 2013 subsequently lost population at three times the rate of other Chicago Black neighborhoods.”

These numbers may be right, but they get the causality backwards: Expected population declines drove school closure decisions, rather than closures driving future population declines.

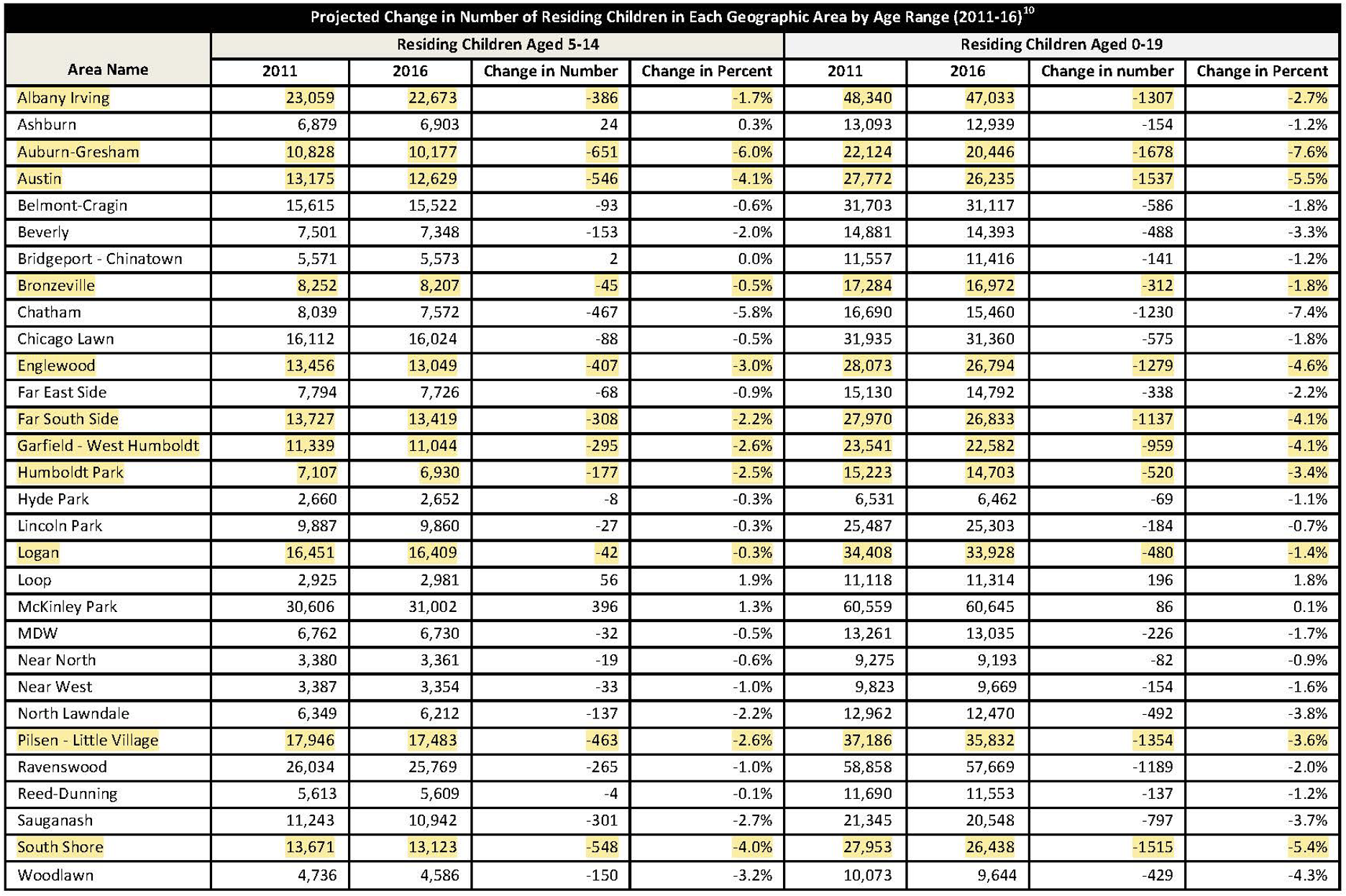

In the run-up to its 2013 consolidation efforts, Chicago commissioned a massive 450-page facilities plan that included, among other analyses, enrollment projections by neighborhood. The report noted that population had declined significantly between 2000 and 2010 in the heavily Black areas on the city’s South and West Sides and projected that the numbers would keep falling further in the coming years in many of these same places.

The table below, taken directly from the 2013 report, shows the change in the number of children in each Chicago neighborhood anticipated between 2011 and 2016. I’ve also highlighted the areas demographers identified as having already undergone “extreme” population loss over the previous decade—a decline in the number of children of more than 5,000. The key takeaway is that the projections anticipated additional declines in the same neighborhoods where population was already sharply falling years before the closures were announced and where affected schools were located.

That population numbers subsequently declined disproportionately in neighborhoods where schools closed suggests that those projections were accurate and the district was wise to use them to target closures in the places it expected student enrollments to keep falling. These numbers provide no evidence that closures caused population losses above and beyond those that were expected to happen anyway.

Oddly, after claiming that “closures contributed” to the population decrease, Toch and Keller acknowledge this point, noting that the data “don’t prove that the school shutdowns accelerated declines in neighborhoods that were already depopulating.”

Claim: District officials exaggerated the budgetary savings from consolidation

When making the case for their right-sizing efforts, Chicago officials estimated that they would save $1 billion over the next decade—roughly half in the form of avoided capital maintenance and upkeep costs and half by reducing the number of building principals and clerical staff. Toch and Keller are right to note that these estimates proved to be off the mark—although the district did save about $250 million over this period on lower administrative and support staffing levels. To say that the savings were exaggerated does not mean that no efficiencies were achieved.

Importantly, however, the district’s budget projections never took into account (and Toch and Keller never discuss) the main way in which building closures save money: by reducing the number of teachers and aides. Instructional staff account for by far the largest budget item in public education, so it makes sense that closures generate the most cost savings by reducing headcounts in that category.

In research for my forthcoming book, which examines school consolidation efforts across the country over the past two decades, I found that school closures cause teacher employment levels to decline by between 5 percent and 10 percent in the affected districts, with class sizes rising modestly and per-pupil expenditures declining by between $500 and $1,000 per year. The reason closures produce such savings is that even massively under-enrolled schools require a minimum complement of teachers to offer a viable education program. Consolidating these buildings reduces the number of teachers by eliminating half-empty classes.

Given the popularity of teachers—and the political power of their unions—it is not surprising that district officials are loath to advertise the fact that building closures will cause teacher staffing to shrink. It is much easier to claim that cost savings will come from elsewhere. But ignoring the staffing changes among frontline educators dramatically understates the actual efficiencies that consolidation can (and do) unlock.

Bottom line: School closures can work, but must be done right

To their credit, Toch and Kelleher conclude their article by writing, “School districts can’t ignore the inefficiencies of under-enrolled schools, especially when they are faltering academically. But the aftermath of Chicago’s school closings a decade ago points to the importance of a clear-eyed approach that prioritizes public transparency and takes into account the financial, academic and community consequences of closings.”

I could not agree more. When closing schools, districts should prioritize academic considerations—most importantly, shuttering schools that post the smallest year-to-year gains in achievement—instead of using budgetary bean-counting to choose the buildings. Community members should avoid dramatic protests, recognizing that efforts to save schools, however well-meaning, could disrupt learning more than the closures themselves. District leaders should be honest with taxpayers that most of the fiscal savings will come by reducing teacher headcounts, not through savings on utility costs or building maintenance needs. They should carry out these staffing reductions strategically by culling the weakest (rather than least experienced) teachers and not rely on attrition alone. And they should make the vacant buildings available to address their communities’ most pressing needs—allowing strong charters to purchase them to increase access to high-quality education options or working with developers to build badly needed housing.

Executed effectively, school closures can be a lever for positive change. Even in Chicago.