Among the many arguments raging—and more than a little mud-slinging—around the Common Core State Standards, perhaps the most arcane involves the blurry border between academic standards and classroom curricula.

Begin with the fact that neither term has a clear definition. Most people hazily understand that standards involve the destination that students ought to reach—i.e., the skills and knowledge (and sometimes habits, attitudes, and practices) that they should have acquired by some point in their educational journey. Often it’s the end of a grade (“by the end of fifth grade, students will know how to multiply and divide whole numbers”), sometimes the completion of a grade band (“by the end of middle school…” or “during ninth and tenth grade”).

Curriculum, on the other hand, is what Ms. Robertson teaches on Tuesday, in week 19, or during the “fourth unit,” and it generally consists of scopes and sequences, actual lessons, textbooks, reading assignments, and such.

Over a stated period of time, curriculum combined with pedagogy, properly applied by teachers and ingested by students, is supposed to result in the attainment of standards.

But it’s blurry. Standards range from vague to specific and from few to numerous. Curriculum ranges all over the place, from a forty-seven-minute lesson to a yearlong, even multi-year scope and sequence.

In general, in the U.S. in 2013, states prescribe standards, at least in core school subjects, but they rarely prescribe curricula, which are typically the responsibility of districts, schools, and/or teachers. On the other hand, some states do recommend model curricula, and some determine which textbooks may and may not be used (at least when state dollars are involved in their purchase). At the local level, too, decisions about curriculum may be centralized or left to the discretion of individual teachers—and this often varies by subject and grade level. Sometimes, curricular decisions get made when the district acquires a “reading program” (in essence, leaving it to the publisher) or when a school signs up for AP World History, the International Baccalaureate, Saxon Math, or Core Knowledge.

Further complicating the picture, some teachers cherish their autonomy in matters curricular and balk at anything imposed or “scripted,” while others yearn for orderly lesson sequences and materials prepared by others.

Into this murky territory come the Common Core standards for English and math, and as expected, they are faulted from both directions. On the one hand, they are criticized as too prescriptive, too much like a “national curriculum,” hence a violation of local control and teacher autonomy. On the other hand, they are faulted for not being accompanied by well-aligned curricular materials, scopes and sequences, or even lesson plans that teachers can use when struggling to convey this sometimes-unfamiliar material to their pupils.

The latest curricular dust-up associated with Common Core involves Appendix B of the English standards, which is, in essence, a long list of readings, selected by those who built the Common Core to illustrate the sorts of passages (fiction, non-fiction, poems, etc.) that students should be able to read with understanding at various points in the K–12 sequence. (If you haven’t viewed it with your own eyes, you can do so here.)

It’s labeled “Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards.”

Its purpose, say its compilers, is “primarily to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they [the passages and titles] are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list.” (Emphasis added.)

Note that the many titles on this list, and the passages selected from them, are not part of the Common Core standards themselves. They are meant to exemplify and suggest—and it’s such a long list that no school system, teacher, or student could conceivably assign, or read, everything on it during thirteen grades. (I doubt that anybody anywhere has read all of everything on it.)

To the extent that I’m familiar with these works and authors, it’s an impressive list: diverse, eclectic, and well stocked with familiar classics but also with much else drawn from sundry genres. See for yourself.

The problem is that, like any list of books, stories, poems, or plays, it contains plenty of items that will be viewed as controversial or inappropriate by individuals and groups on myriad grounds: ethnic, religious, political, moral, and on. I suspect there’s nothing on the list that’s completely inoffensive to everyone in America. (The Wizard of Oz is there, for example, and it contains witches. Thurber’s “The Thirteen Clocks” may alarm those who are superstitious about numbers. As for Walt Whitman, he is said to have been fond of other men. Let’s not even talk about what Oedipus did.)

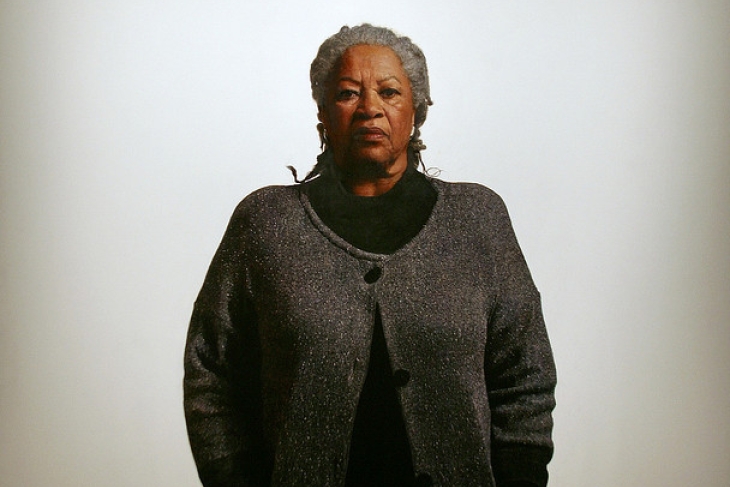

The big recent dust-up involves The Bluest Eye, a novel by the Nobel Prize–winning African American author Toni Morrison, a short excerpt from which appears on page 152 of the appendix, intended for eleventh graders. (It’s there along with Poe, Hawthorne, Faulkner, Melville, Bronte, Shakespeare, Keats, etc.)

I find the excerpt complex, demanding, and a bit obscure, but not offensive. You may disagree. Still, there’s no denying that the book as a whole, while praised by many for its literary merit, also contains parts that can fairly be termed “adult literature.” To some people’s eyes, they’re pornographic, unsuitable for school kids of any age.

People differ in these matters: as to what they regard as obscene, what is appropriate for students of various ages, and what schools should expose them to. (Recall the contention over whether school libraries should have The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn on their shelves.)

Let’s be clear, as Diane Ravitch showed in The Language Police, that when you scrub every library, every reading list, every textbook, and every test item clean of everything that could offend anybody for any reason, you end up with the boring pablum that dominates so much of today’s curriculum. One reason American kids don’t read much is because what remains for them to read is so dull. Is it any wonder the Internet is more beguiling?

Yet the policy dispute remains: If a state adopts the Common Core standards, is it requiring, recommending, or even hinting that its public school pupils should (or must) read all—or any—of the items that are listed and excerpted in Appendix B?

The short answer is no. Appendix B isn’t part of the standards and nothing on it needs to be read by anyone. The choice of curricular materials remains entirely within the province of the state, district, school, or teacher, according to standard practice in that locale.

When Debe Terhar, who chairs the Ohio State Board of Education, noted that Appendix B had made it onto the website of the state education department, she questioned whether anyone in that agency had actually read the works on that list. Of The Bluest Eye, she said “I don’t want my grandchildren reading it, and I don’t want anybody else’s grandchildren reading it.”

Unlike the Arizona district that recently banned a different book on the Appendix B list, Terhar was not calling for the Morrison book to be outlawed in Ohio. But she doesn’t think it’s appropriate for the state in any way to endorse—or even appear to endorse—the book for classroom use, even in the eleventh grade.

Toni Morrison, the ACLU, and various commentators promptly jumped on Ms. Terhar, accusing her of censorship and worse.

But let’s go back to basics. When Ohio adopted the Common Core standards for English language arts, it did not adopt Appendix B. The standards themselves contain a shorter list of illustrative readings that does not even mention Toni Morrison. (That list—for grades 6–12—can be found on page 58 of the standards.) But that list, too, is only illustrative of the kinds and levels of reading that the standards are supposed to be applied to; it is not a list of titles that teachers must assign or kids must read.

Perhaps the Common Core authors should have been more prescriptive. E.D. Hirsch, who knows more about curriculum than anyone I know, finds much to praise in the standards but faults them for not setting forth a “coherent,” content-specific curriculum.

You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. Maybe Hirsch is right and the standards should spell out exactly what kids should learn, which is apt to include what they should read. But the Common Core doesn’t do that. Which means it’s wrong to attack Ms. Terhar for objecting to one entry on a list that is not, in fact, part of the standards. To her eye (and the eyes of more than a few other responsible adults), that particular book isn’t suitable for teenagers. But nothing in the Common Core says they have to read it. For better and for worse, such decisions remain where they have always been in American education.