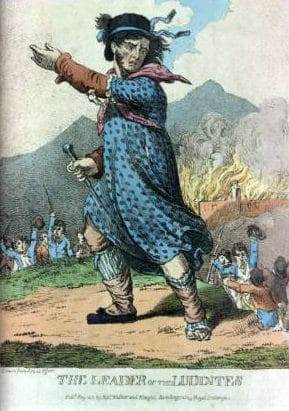

Admittedly, Andy Smarick is part Luddite. From Wikimedia Commons. |

I just finished reading the Forbes Magazine profile on Salman Khan. You might want to give it a read.

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, I’m somewhere between marginally skeptical and cautiously optimistic when it comes to the proliferation of technology to “individualize” learning.

Admittedly, I’m part Luddite and part contrarian, so I’m predisposed to be chary of this entire field for less than noble reasons. But it seems like the only thing more ubiquitous than new ways to deliver content are the apocryphal claims of their revolutionary nature. (Along these lines, I highly recommend Rich Hess’s thoughts on the Khan article and our history of overhyping and misusing technology.)

But I’m slowly being swayed. On the positive side, a bunch of smart people I know are pretty certain that this really is a disruptive innovation and that things will never be the same once parents realize they can truly direct their children’s education. Also, I’ve read a bunch of RTT-D applications, and, for the most part, they provide some confidence that some LEAs are serious about using newer technologies to truly change instruction.

On the pessimistic side, lots of people predicted that NCLB choice and SES were going to be game-changers because they empowered parents to direct their children’s education, and to my everlasting chagrin, that was not to be. And the RTT-D applications also convinced me that lots of districts are not prepared to use technology in meaningful ways.

It’s in this context that I approach Khan Academy, unquestionably a remarkable development—some call it the world’s largest school—that is touching millions of kids. Scads of people are over the moon for it, but for the reasons listed above, I’ve been reluctant to jump aboard. So I read this article with eyebrow raised and guard up.

There are definitely reasons to be intrigued, even excited. Mr. Khan has made an amazing amount of material available. As we move toward truly personalizing learning—setting clear academic standards and tailoring instruction to each student’s needs—this type of access to substance is imperative.

But left unaddressed are basic questions about the quality of the content. According to the article, most of the site’s 37 employees are software developers, not content experts, and Mr. Khan delivers more than 3,000 of the lectures himself. Hmm.

I’ll admit to being very interested in one aspect of using technology to personalize learning: the generation, analysis, and use of data that heretofore has been impossible.

This seems like another step in the “democratization” of information. Just like Wikipedia was to the encyclopedia and blogging was to traditional reporting, Khan is to classroom content as we’ve long known it. The article quotes Knewton CEO Jose Ferrieira: “Recent history teaches us that the Internet ultimately revolutionizes any industry that has an information or media-based product.”

Yes, more substance than once imaginable is now at our fingertips, and that’s a sea change for sure. But we also have more reason to question its reliability. Book and newspaper editors used to be the quality filter (imperfect for sure, but pretty reliable); now we have to use a range of personal strategies to suss out what’s trustworthy. If we’re to entrust some portion of our kids’ learning to free online providers, parents and others will need to play a much larger mediating role.

This is one of many reasons to pump the brakes, but the feeling I get from this article and so many people in education technology is that this train is already hurtling down the tracks at near-terminal velocity. Evidently, a growing number of young people prefer online courses, and according to the article, this world is attracting massive amounts of new venture capital.

All this suggests that we need some middle ground, a combination of submission to technological advancement and—paraphrasing Buckley’s formulation of conservatism’s virtue—standing athwart history, yelling, “Stop!”

Despite this qualified backing of our current path, I’ll admit to being very interested in one aspect of using technology to personalize learning: It’s the generation, analysis, and use of data that heretofore has been impossible.

Knewton’s Ferriera gives it voice: “Once you have device-based learning, you are producing so much data we know everything about what you know and how you learn best…You learn math best in the morning, between 9:30 and 11 a.m. We know that. That 40-minute burst you do at lunch every day? You aren’t retaining any of that—go hang out with your friends. You learn science best with video clips or games instead of text or in addition to text? You learn history best in 22-minute bite sizes, and at the 24-minute mark your click-rate always declines? We know everything about how you learn.”

If taken too far, this verges on eerie Big-Brother-ism. But if done right, it could combine cognitive science, smart instruction, and high-quality content to help kids learn much more.