This is the final entry in a three-part series looking how American high schoolers feel about our education system, and how engaged they are in their classroom. Each iteration is based on the findings of Fordham’s What Teens Want from Their Schools, a report published last year based on a survey of students from forty-eight states and the District of Columbia who representing all types of schools—traditional public, public magnet, parochial, independent, and charter.

The first explored how young people feel about different activities, from teacher lectures, to group projects, to student presentations. (The general answer? Not very enthusiastic, but it depends on individual teachers and classrooms.) The second looked at what students say about their own approaches and attitudes toward school. (Teens are—surprise!—inconsistent, and a lot of students who are phoning it in at least some of the time.) This one discusses the ways in which different student groups and students at different types of schools report different levels of engagement.

Although high schoolers are often are uninterested in classroom activities and frequently put in less than their best effort, there’s much variance between individual students and student groups. These differences sometimes correlate with results on academic achievement—but not always. So looking at which students report more engagement might provide clues as to where schools are managing to interest their students—and where they need to devote extra attention.

To describe differences in engagement across groups, we classify students as “engaged” when they express interest (being “very interested” or “extremely interested”) in at least five of the nine classroom activities the survey asked them about, or when they are “extremely interested” in at least three of the activities. Our definition of engagement is admittedly imperfect; a student who expresses disinterest in most activities could still be interested in the material and committed to learning. Also, readers should keep in mind that our measure comes from students’ self-reported interest and engagement, not an external measure. But research has shown that the relationship between interest and learning outcomes is real, and our results show notable differences in interest levels among different groups, regions, and school types.

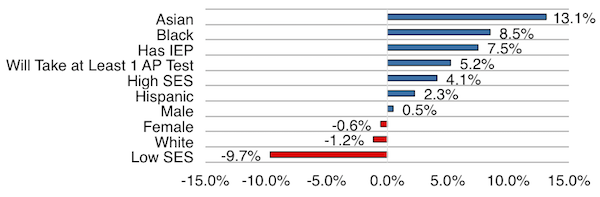

Overall, 40 percent of students meet this definition of engaged students. But as figure 1 shows, there are substantial differences across groups. Asian and black pupils report greater engagement than their Hispanic and white peers; students with individualized education plans (IEPs) and those who will take at least one AP test are more engaged than others; and students of low socioeconomic status (SES) are the least engaged group of students that we analyze. Gender, however, seems to be unrelated to engagement.

Figure 1: Asian and black students and students with IEPs are the most engaged, while low-SES students are the least engaged

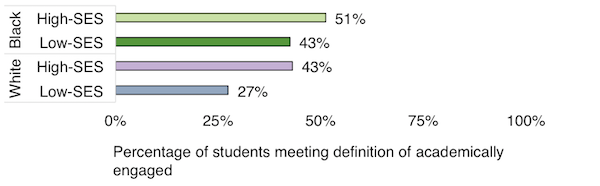

While race and SES are correlated in our sample, with white students more likely to be high-SES and black students more likely to be low-SES, our measure of engagement cuts across this divide. In fact, as figure 2 shows, the disengagement of low-SES pupils is entirely driven by white students, of whom only 27 percent meet the definition of engagement. Although those of high-SES are far more likely to be engaged than peers of low-SES, low-SES black students are just as engaged as their high-SES white counterparts. Of these groups, the group expressing the most engagement is high-SES black students, of whom 51 percent are engaged.

Figure 2: Black students and high-SES students are highly engaged

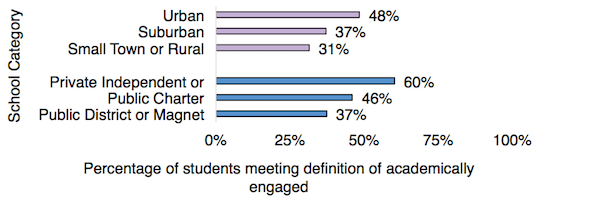

Geographic areas also show substantial differences in engagement, with students in small towns and rural areas reporting much less engagement than their urban peers. Just 31 percent of students at small town and rural schools, compared to 48 percent of urban students, meet our definition of engagement, though neither number is one to celebrate. The particularly low levels of engagement among both low-SES white students and students in small towns and rural areas dovetails with other research about the decay of white working class communities.

Figure 3: Students in private schools and students in urban schools are more engaged

Differences in engagement are also pronounced when looking at different types of schools. Forty-six percent of public charter students and 60 percent of private school students meet our definition of “engaged.” Of course, we can’t say whether these findings are actually effects of the different kinds of schools or just reflections of self-selection, in which kids who are more likely to be engaged tend to enroll disproportionately in private or charter schools. But at the very least, this represents evidence that charter high schools, and private schools even more so, are generally more engaged learning environments than traditional public high schools.

One suggestion does emerge from these results: Invest in attention. The results from private schools and students with IEPs suggest that teens respond to smaller environments where they are likely given more personal attention, which educators will respond is obvious—and often nearly impossible. But even private schools show an engagement rate of only 60 percent, while less than half of students with IEPs qualified as engaged.

These results confirm the existence of a serious, nationwide problem of teen disengagement that stretches across racial, geographic, and socioeconomic lines. But maybe these results can be a call to action, both for researchers, who need to figure out more about when and why students are losing interest, and for the education reform community. A lack of student engagement is a fundamental obstacle to learning, and it’s time to tackle it with the urgency it deserves.