Fights over books, an exodus from public schools, politically obsessed adolescents, the need for civics education—Horace Mann predicted it all back in 1848. Thankfully, this education luminary also provided wisdom and insight in the common school era for how we can turn down the culture war heat in modern times.

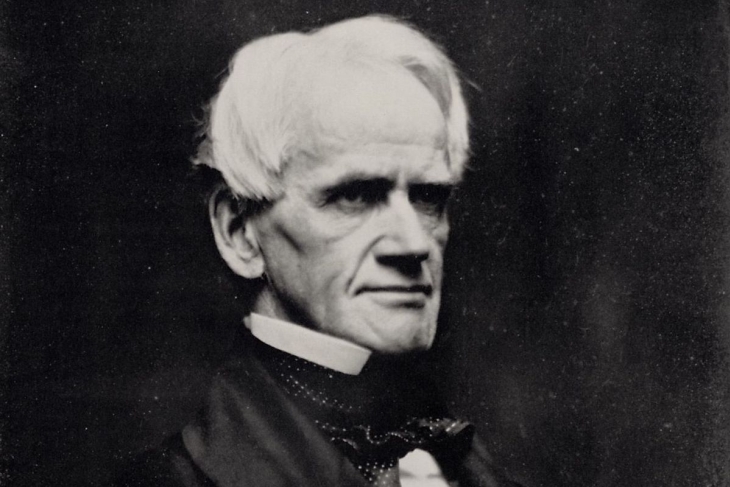

In case anyone reading this doesn’t already know it, Horace Mann is considered the founder of modern American public schools. A rising star in Massachusetts politics, back in 1837 he shocked his peers by accepting a then-insignificant role as secretary of the Massachusetts Department of Education. With little money or power, he began crafting what became widely circulated and influential annual reports, detailing the need for publicly funded, publicly run, universally attended schools. And in his final report, he spilled much ink warning his readers exactly what would happen if we allowed politics into our classrooms.

Today, as is well known, our public schools are struggling. They have always been a place of contention in America, but the fights have been distinctly acrimonious of late. Once sleepy affairs, school boards resemble raucous, fiery, even violent battlegrounds—as both conservatives and liberals contend over value-laden debates over books, curricula, and other topics of instruction.

Schools cannot help but inculcate some sort of worldview. What books are read, what behavior is rewarded or punished, who selects curricula, offhand remarks from teachers, uniform rules—everything a school does communicates to students implicit ethical messages and political encouragements. If this philosophy veers too far in any direction from the broader zeitgeist, parents will rightly take umbrage and look elsewhere.

Horace Mann foresaw this risk. He asked, “If parents find that their children are indoctrinated into what they call political heresies, will they not withdraw them from the school?” Astutely, he predicted that, in a politicized education, a central issue would be curriculum wars over what books kids should read: “What better could be expected, than that one set of school books should be expelled, and another introduced, as they might be supposed, however remotely, to favor one party or the other?”

In perhaps the most amusing passage, he describes schoolrooms that could become “a miniature political club-room” full of political addresses “prepared by beardless boys, in scarcely legible hand-writing, and in worse grammar.” As action civics replaces studying the Constitution, students partake in mock rallies, high schoolers have become international talking heads, and both cursive and grammar instruction fall out of favor, I can’t decide if I should laugh or weep at Mann’s caricature.

Thankfully, Mann didn’t leave us without recourse. He acknowledged that squabbles over public education are inevitable. Get a few hundred families together to collectively educate their children, and conflicts will arise almost necessarily. But to keep such conflicts productive and civil, he recommended a few essential topics for instruction:

The constitution of the United States, and of our own State, should be made a study in our Public Schools. The partition of the powers of government into the three co-ordinate branches—legislative, judicial, and executive—with the duties appropriately devolving upon each; the mode of electing or of appointing all officers, with the reason on which it was founded; and, especially, the duty of every citizen, in a government of laws, to appeal to the courts for redress, in all cases of alleged wrong, instead of undertaking to vindicate his own rights by his own arm; and, in a government where the people are the acknowledged sources of power, the duty of changing laws and rulers by an appeal to the ballot, and not by rebellion, should be taught to all the children until they are fully understood.

Not a bad civics curriculum: We should read the Constitution with our students, teach them how our government functions, and impress upon them their duties as citizens. More enlightening than a list of topics to cover, though, is Mann’s explanation for how learning about the proper functioning of our government will facilitate healthy disagreement. The reasons are two.

First, very practically, civics education will help people understand that there are proper and effective mechanisms to enact political changes, such as “the machinery of the ballot” or the court system. When we have a means to influence policy, political passions can vent without the need to resort to “violence.” Without a proper understanding of political processes, anger manifests in unruly school board meetings or the needless harassing of school officials instead of productive political engagement.

Second, civics education unifies through the creation of shared experiences, a shared cultural knowledge, and shared civic values—inculcating a common valorization of, for instance, equality before the law and religious toleration. These common beliefs, really a form of civil religion, form “the only common ground, whence the arguments of the disputants can be drawn.” With shared civic dogmas about the rights of man, the nature of government, and the purpose of society, we shared a common set of beliefs—a common language and rules of disputation—through which we can hash through our disagreements.

Now, I’m no fan of needless vitriol or baseless name-calling, but many of the arguments undergirding the so-called culture wars—what should our kids learn, how should we frame our history, who has authority to determine which policies—are inevitable, healthy even. The question of what values get taught in schools is an important one, and one that should be decided in the public square. But these arguments will prove productive and keep from descending into needless mud throwing only if we begin with a common ground. Without that, political impasse results.

Horace Mann brought public education mainstream, and this achievement warrants adulation. But if we go back and read his arguments, we find that they changed the nation precisely because they were powerful, convincing polemics, full of wisdom that can and should influence our politics and policy today.