Editor's note: This post has been updated with the full text of "Don't know much about history."

Pop quiz! Try to answer the following questions without Googling: What is one right or freedom named in the First Amendment? We elect a U.S. senator for how many years? Who is the governor of your state? Easy, right? Here’s a tougher one: How much confidence do you have in your fellow citizens who cannot answer these questions as voters and participants in our democracy?

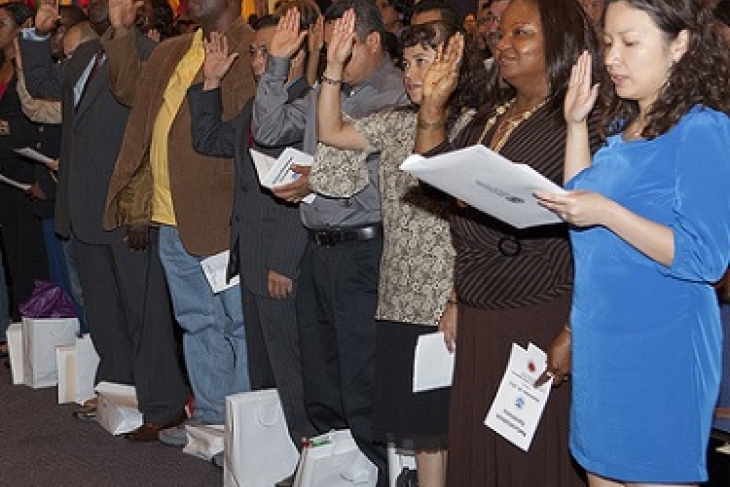

These are among the hundred questions about history, civics, and government on the U.S. citizenship test, which immigrants must pass as part of the naturalization process. It’s not a particularly challenging exam. Would-be citizens are asked up to ten of the questions; a mere six correct is a passing score.

In January, Arizona and North Dakota became the first two states to make passing this test a high school graduation requirement; South Dakota and Utah have followed suit this month. Similar bills have been introduced in more than a dozen other states.

“I would submit that a minimal understanding of American civics is of real value and therefore worthy of measurement,” said Arizona State Senator Steve Yarbrough. I agree. Even in our test-mad era, requiring a rock bottom, minimal knowledge of basic civics shouldn’t be too heavy a lift.

Even though a mediocre elementary education should enable you to pass the test with relative ease, making the test a graduation requirement is not the no-brainer common sense might suggest. People who take civic education seriously (yes, they exist) fret that states that adopt the citizenship test may be tacitly encouraging their schools to abandon more rigorous, semester-long classes in civics. I’m skeptical. At present, more than 90 percent of U.S. high school grads get a semester in civics and at least a year of U.S. history. But something is clearly not sticking. A Xavier University study showed that while 97.5 percent of those applying for citizenship pass the test, only two out of three Americans can do the same. Raise the bar to answering seven of ten questions correctly—still pretty low—and half of us fail. It’s hard not to wonder what exactly kids are learning in those ostensibly rich and rigorous civics classes.

Critics doth protest too much. There’s no conflict between classes that seek to develop deep civic engagement and establishing a minimal level of civic knowledge as a public school exit ticket. And the failure of so many Americans to answer even basic questions like, “What stops any one branch of the government from becoming too powerful?” (while demanding that naturalized citizens know as much) is something of a national embarrassment.

It’s hard to overstate just how poor is the average American student’s grasp of civics and history—or how badly we need to breathe life into civics in our schools. The most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that about one-third of American eighth graders scored at or around proficiency in reading, math, and science. But those are robust numbers compared to civics and history, where 22 percent scored at that level. But we needn’t worry about those embarrassing scores any more. In 2013, the National Assessment of Education Progress, perhaps believing that ignorance is bliss, announced that the civics and history tests historically given in the fourth, eighth, and twelfth grades would thenceforth only be administered in the eighth grade.

Nearly every impulse in contemporary education has conspired to cement civics’s status as an education backwater. High stakes testing focuses on reading and math. Americans are far more likely to see education as a means of personal progress, the ticket to higher education, a good job and upward mobility. However, education for citizenship was the founding principle of public education. America’s earliest thinkers about public education—men like Benjamin Rush and Noah Webster—saw citizen-making as a fundamental purpose of education. We may safely assume that Horace Mann went to his grave never once having uttered the phrase “college and career ready.” Requiring students to pass the simple citizenship test may not usher in a civics renaissance, but it is a modest and welcome first step toward restoring the public purpose of public education. Here’s hoping other states follow suit, perhaps ushering in a modest civics revival.

To be sure, no one should believe that, if every child in the land could name the authors of the Federalist Papers (another question on the test) or a single accomplishment of Susan B. Anthony or Martin Luther King Jr., we will have solved the civic education crisis in America. We won’t. But insisting our children pick up at least a minimal level of shared knowledge of civics and history is a good place to start. And not too much to ask.